On the Volume of the Platonic Solids

How big are the Platonic solids in relation to one another?

The Platonic solids have been known for millennia. They bear the name of Plato, who spoke of them in his dialogue Timaeus. He describes their “construction” (sans the dodecahedron) from the most basic “isosceles and scalene” triangles, or in modern parlance, “45-45-90 and 30-60-90” triangles, respectively. However, the construction was not mathematical, and to my knowledge, each solid was first rigorously described from first principles in Book XIII of Euclid’s Elements.

In my teenage years, I recall viewing articles on the solids with their volumes proudly displayed next to their surface area. While surface area may be troublesome in the case of the dodecahedron (as the geometry of regular pentagons is not widely taught), it is easy enough for grade schoolers to calculate for cubes, and for trigonometry students to calculate for the solids composed of equilateral triangles. On the other hand, the volume is somewhat mystical.

Fortunately, edge length is the only free variable in a Platonic solid, meaning their volumes can be parametrized by this value alone. The volume itself is a meaningless quantity for comparison unless put in ratio with another volume, but since the cube has such simple expression for its volume (the edge length cubed), it is a natural choice for this comparison1.

This post will calculate this ratio without using any trigonometric functions (sine, cosine, tangent), instead opting for a more compass-and-straightedge approach. Consequently, it becomes more natural to calculate the square of the volume to better cooperate with the Pythagorean theorem.

A Recap of Geometry

For those with only a vague recollection (or perhaps none at all) of geometry, this section is intended as a refresher.

Planar Geometry

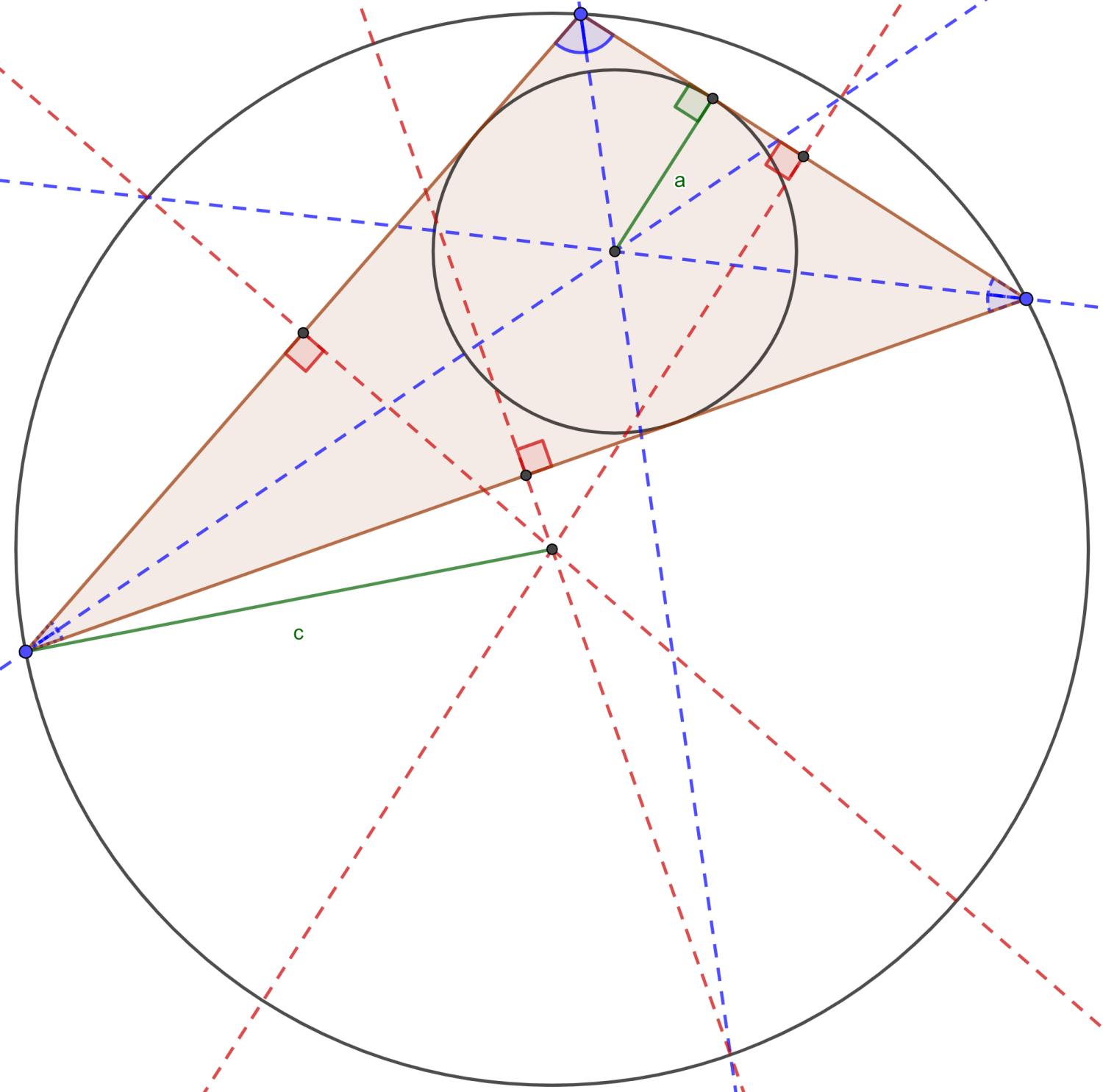

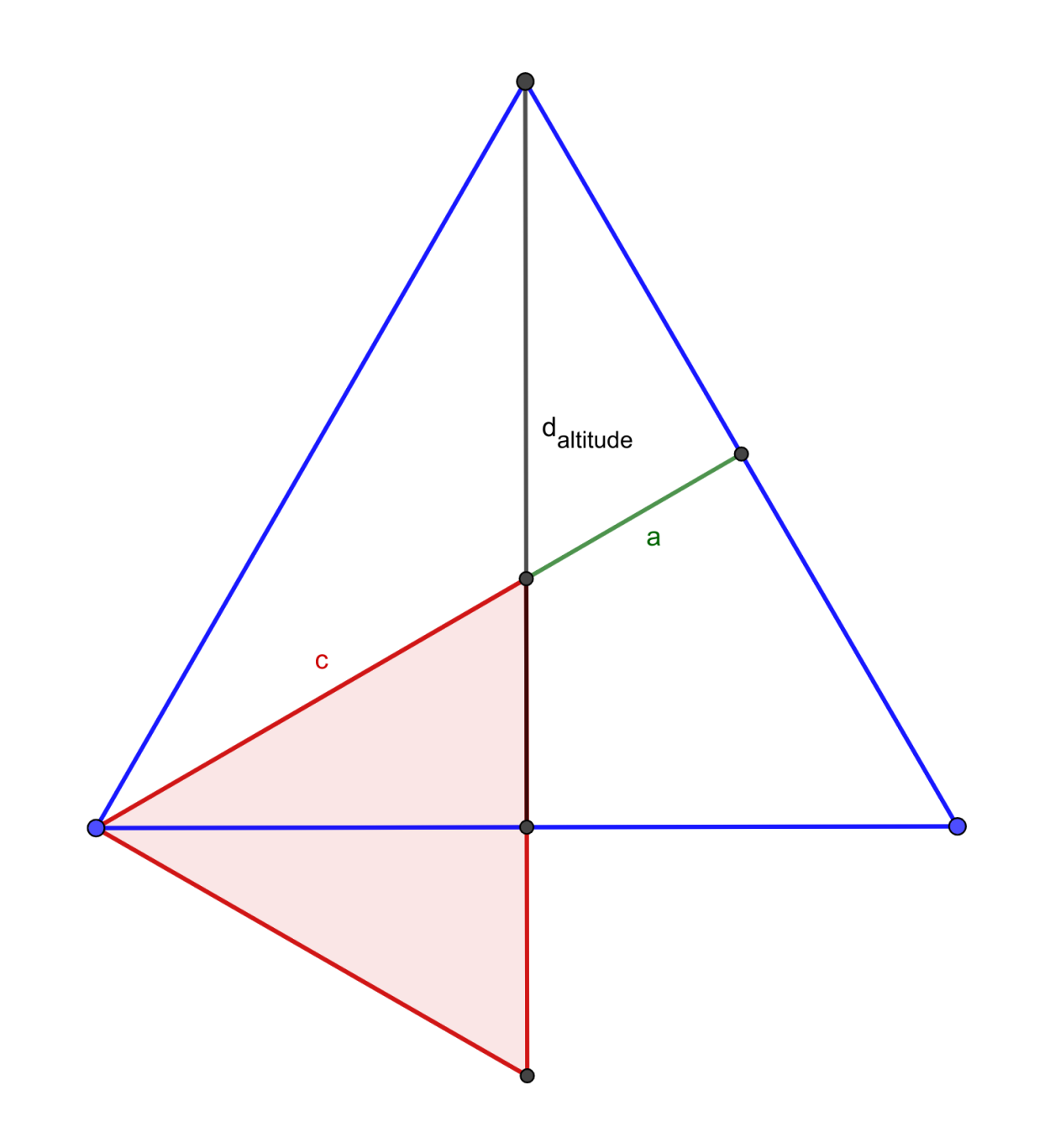

There are many centers of a triangle, but for us, two are of primary interest:

- The circumcenter is equidistant from every vertex. In other words, it is the center of a circle containing all three vertices.

- It can be constructed by finding the intersection of the edges’ perpendicular bisectors.

- The distance from a vertex to the circumcenter is called the circumradius (c).

- The incenter is equidistant from every edge. It is the center of a circle which lies tangent to every edge

- It can be constructed by finding the intersection of the lines which bisect each angle.

- The perpendicular distance from an edge to the incenter is called the inradius (a).

The inradius is special because it is also an altitude for a triangle formed by the inradius and an edge of the larger triangle. This means that the area of the larger triangle is the sum of these smaller triangles.

\begin{align*} A &= \left ({e_1 a \over 2} + {e_2 a \over 2} + {e_3 a \over 2} \right) = \left ({a \over 2} \right ) (e_1 + e_2 + e_3) \\ &= {Pa \over 2} \end{align*}

This gives an expression for the area. For an equilateral triangle, these two centers coincide. This is because the perpendicular bisectors of the edges are the angle bisectors. In fact, the bisection of an angle involves constructing a rhombus, which is made up of two isosceles triangles (of which the equilateral triangle is a special case). In this case, the inradius is also called the apothem, and the difference between it and the circumradius is immediately apparent and called the sagitta (s).

This idea of incenters and circumcenters can be extended to other 2D figures such as the square and regular pentagon. For a square, the center is simply the intersection of the diagonals (i.e., the diagonals’ common midpoint). The pentagon is trickier and will be discussed later. Regardless, the expression for the area {Pa \over 2} still works, since the polygon can be triangulated through the center in a similar way.

Cubes, Prisms, and Pyramids

Now we speak of 3D geometry. The volume of a prism is equal to the height times the area of the base, where the “height” is orthogonal to the plane of the base. Pyramids with the same height and base have one-third this area.

V_\text{prism} = Bh,~~ V_\text{pyramid} = {Bh \over 3}

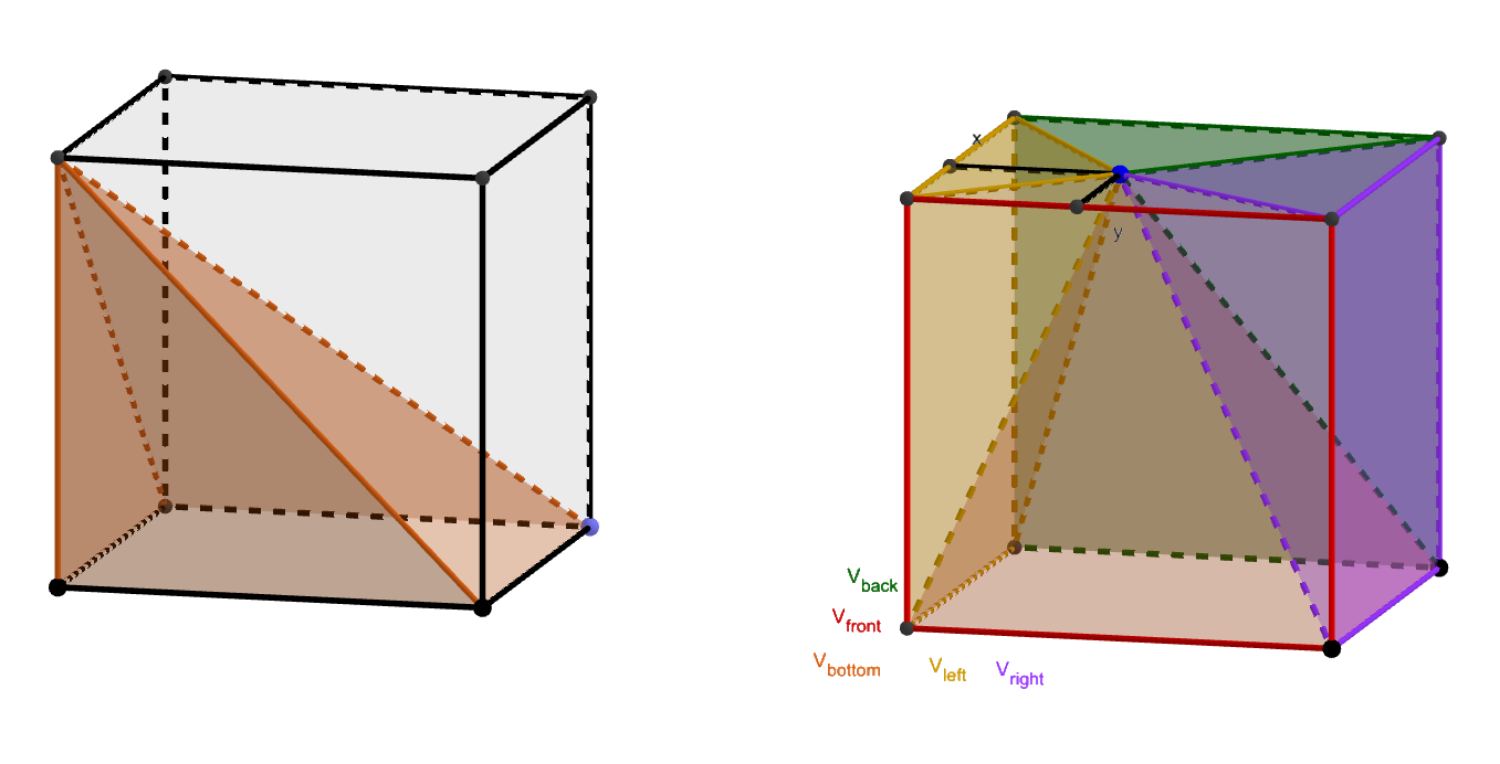

This volume formula can be made more intuitive by considering the cube. The pyramid formed by one of the faces and an edge perpendicular to it will contain one square and two half-squares, or two squares in total. Therefore three pyramids are needed to recreate all six faces of the cube.

For a slightly more detailed explanation, consider a point inside the face on top of the cube. Its (perpendicular) distance from one edge is x and its distance to an edge adjacent to that is y. Connecting all other bases to this point produces five pyramids, whose bases all have the same area. Designate these pyramids as “bottom”, “left”, “right”, “front”, and “back”, where left and right correspond to x and front and back correspond to y.

\begin{align*} V_\text{cube} &= Bh = V_\text{bottom} + V_\text{left} + V_\text{right} + V_\text{front} + V_\text{back} \\ &= rBh + rBx + rB(h-x) + rBy + rB(h-y) \\ &= rBh + rBh + rBh \implies 1 = 3r \\ r &= {1 \over 3} \end{align*}

This can be generalized to a pyramid based on any prism, where the top point lies in the plane of one of the bases. However, this is beyond the scope of this post.

Simplifying Units

Though it may make sense to use unit lengths for the edges of 3D figures, bisection of edges is easier if the edges are composed of two units. This happens to coincide with Plato’s description – the equilateral triangle is described as being formed from two 30-60-90 triangles. That is, the edge length of the equilateral triangle was twice the “unit” length: the shortest side of the 30-60-90 triangle.

Thus, ratios to the volume of the unit cube must be adjusted by a factor of 8:

\begin{align*} { V_\text{solid}[2] \over V_\text{cube}[2] } &= { V_\text{solid}[1] \over V_\text{cube}[1] } \\ \implies V_\text{solid}[2] &= { V_\text{cube}[2] \over V_\text{cube}[1] } V_\text{solid}[1] \\ &= { 2^3 \over 1 } V_\text{solid}[1] \end{align*}

Simple Solids: the Octahedron and the Tetrahedron

While “simple” is a bit of a misnomer, their volumes do not require regular pentagons, and are therefore easiest to appreciate.

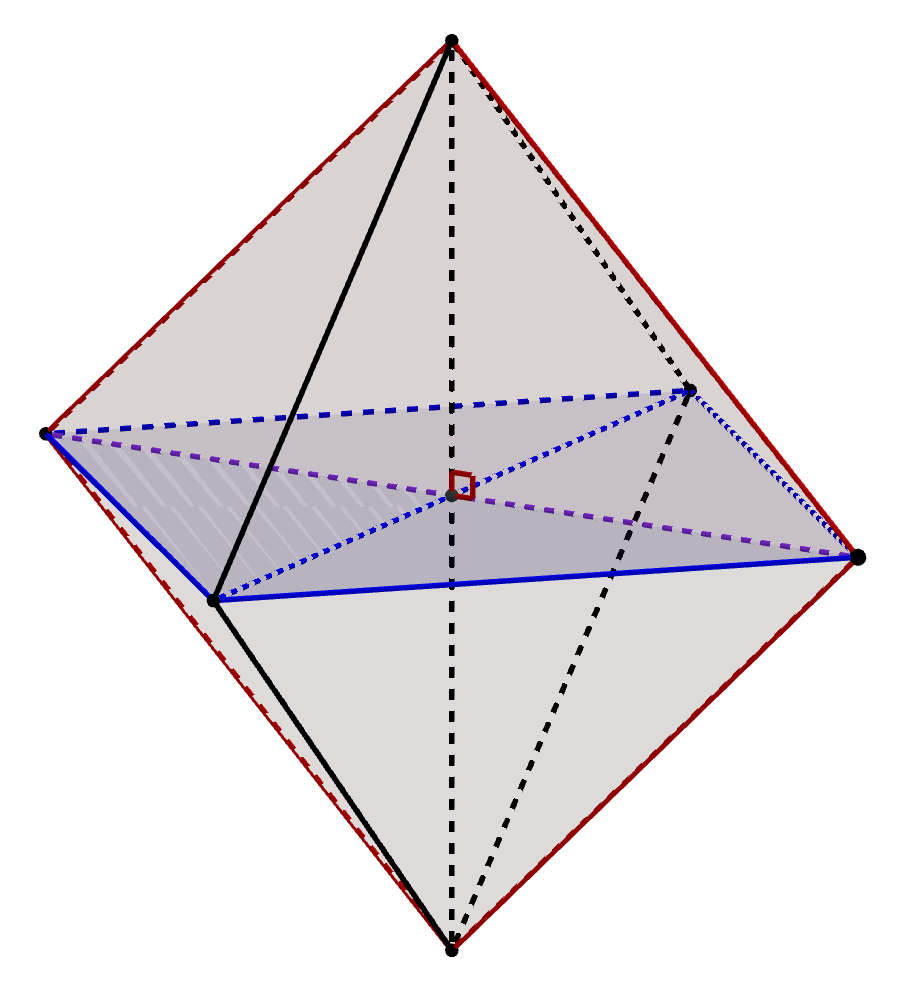

Octahedron

The octahedron can be thought of as two square pyramids joined end-on-end, with uniform edge length throughout. Since the base of the pyramid is a square, its center is equidistant from the vertices of the base. Due to the symmetry of the octahedron, this center is the same no matter which square we pick. Thus, the altitude h of the square pyramid is simply half of the diagonal of the square.

(2h)^2 = e^2 + e^2 = 2 \cdot 2^2 = 2^3

Therefore, the volume of an octahedron is:

\begin{align*} B^2 &= (e^2)^2 = (2^2)^2 = 2^4 \\ (2 V_\text{sq.pyr.})^2 &= (2^2) \left( {B^2 h^2 \over 3^2} \right) = {B^2 (2h^2) \over 3^2} = {{2^4 \cdot 2^3} \over 3^2} = {2^7 \over 3^2} \\ (2^3 \cdot V_\text{oct})^2 &= {2^7 \over 3^2} \implies V_\text{oct}^2 = {2 \over 3^2} \\ V_\text{oct} &= {\sqrt{2} \over 3} \end{align*}

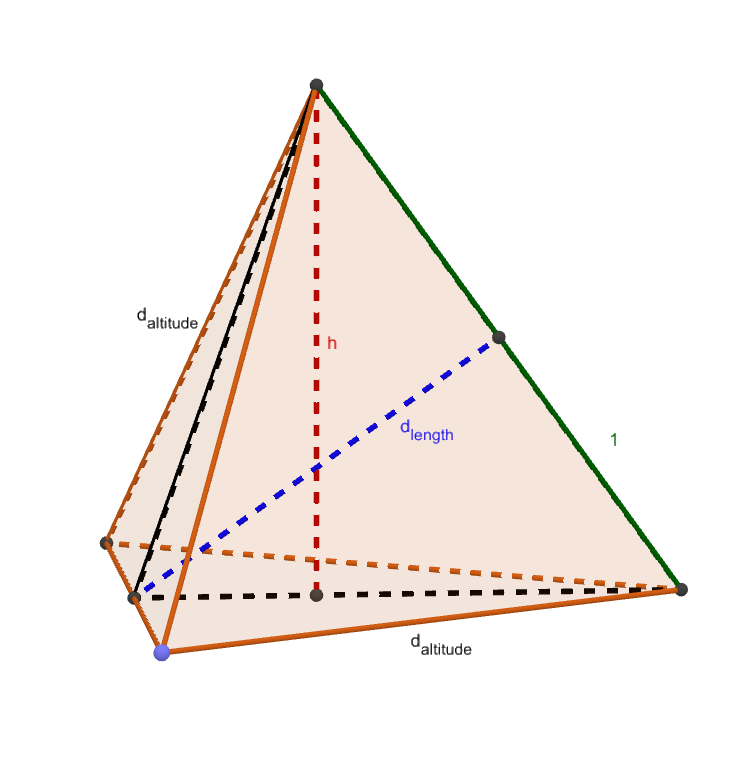

Tetrahedron

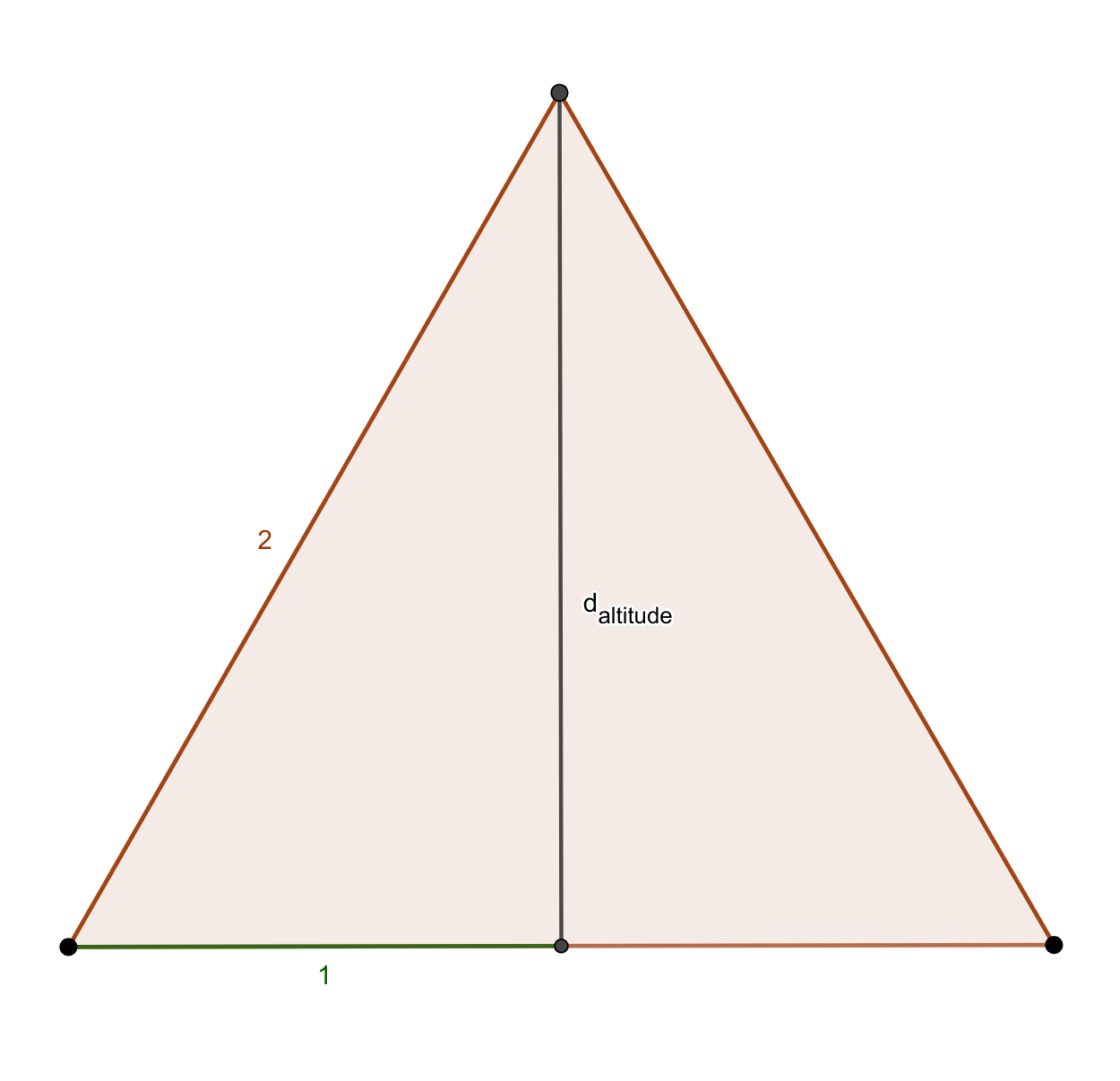

Since the tetrahedron is itself a pyramid, its volume follows from the earlier formula. First, we must calculate the (square of the) area of the base of an equilateral triangle.

\begin{align*} d_\text{altitude}^2 &= \textcolor{orange}{2}^2 -\ \textcolor{green}{1}^2 = 3 \\ B^2 &= \left ( {2 \cdot d_\text{altitude} \over 2} \right )^2 = 3 \end{align*}

Next, bisect this triangle through any edge, then use it to bisect the tetrahedron through the plane containing this line and the remaining edge. This forms an isosceles triangle containing an edge and the altitudes of two faces. Bisecting the angle where the two alittudes meet (perpendicularly) bisects the edge.

\begin{align*} \textcolor{blue}{d_\text{length}}^2 &= d_\text{altitude}^2 -\ \textcolor{green}{1}^2 = 2 \\ (2A_\text{center})^2 &= (2d_\text{length})^2 = (\textcolor{red}{h} d_\text{altitude})^2 \\ &= 4 \cdot 2 = 3h^2 \\ h^2 &= 8 / 3 \end{align*}

Since h is known, we can calculate the volume.

\begin{align*} ({ 2^3 \cdot V_\text{tet} })^2 &= {B^2 h^2 \over 3^2} = {3 \cdot (8/3) \over 3^2} \\ V_\text{tet}^2 &= {8 \over 2^6 \cdot 3^2} = {1 \over 2^3 \cdot 3^2} = {1 \over 2 \cdot 6^2} \\ V_\text{tet} &= \sqrt{1 \over 6^2 \cdot 2} = {1 \over 6\sqrt 2} \end{align*}

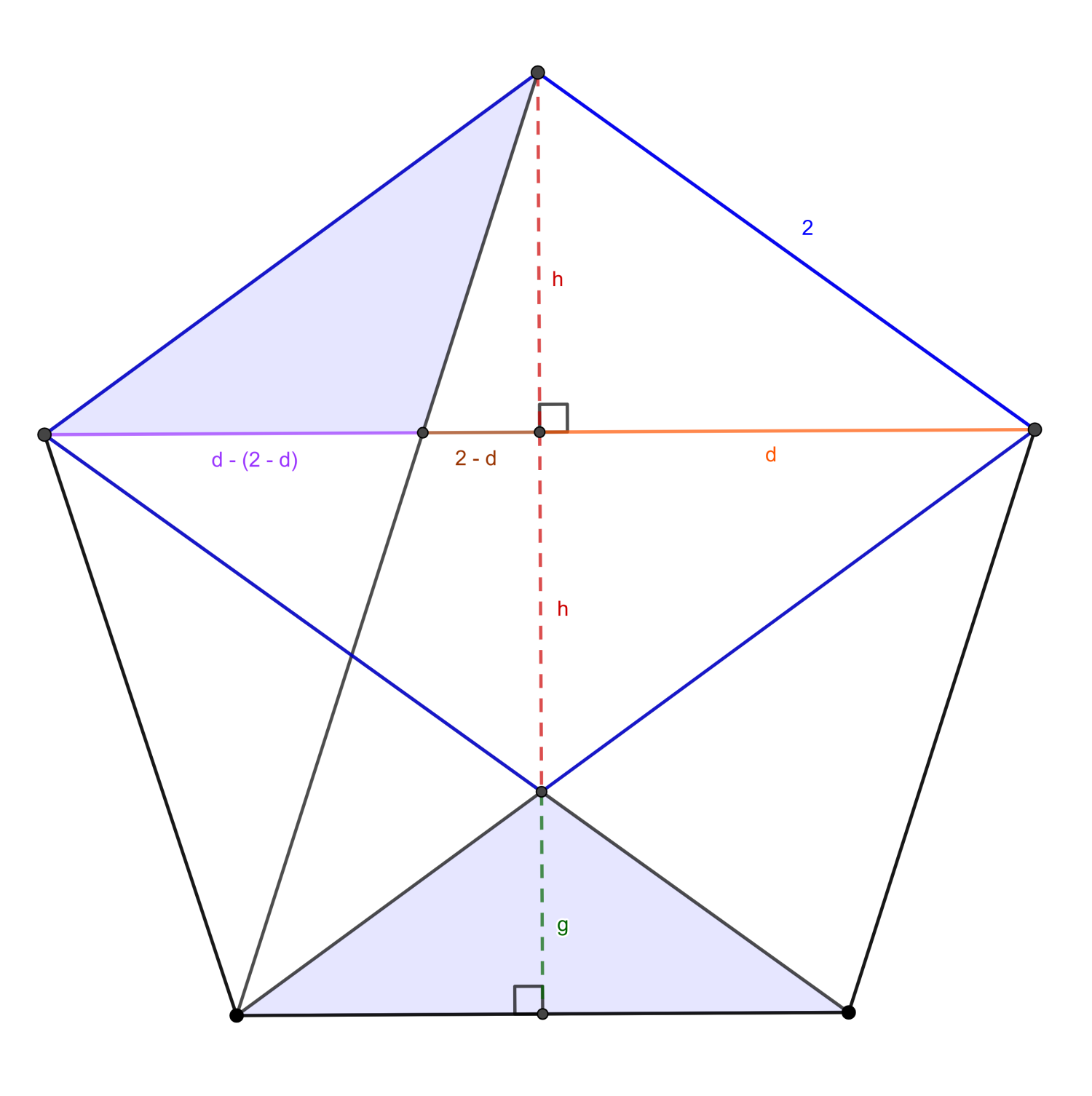

Returning to 2D: Regular Pentagons

Both of the icosahedron and dodecahedron contain regular pentagons. Thus, it is necessary to examine them in detail.

The regular pentagon has five diagonals, which form a pentagram. Since all angles in a regular pentagon are equal, the trapezoid formed by three consecutive edges and one diagonal is isosceles. This means the diagonal is parallel to one of the edges, which applies to all diagonals by symmetry.

Since the diagonal is parallel to one of the sides, a parallelogram can be formed from two sides and segements from two diagonals. More specifically, this parallelogram is a rhombus, since the segments must have equal lengths to the sides.

Bisect the pentagon vertically and let the length of half of the diagonal of a pentagon be d, half the length of the other diagonal of a rhombus be h, and the remaining height of the pentagon be g.

\begin{align*} \textcolor{orange}{d}^2 + \textcolor{red}{h}^2 &= \textcolor{blue}{2}^2 \\ 2\textcolor{darkblue}{A_\text{blue}} &= 2\textcolor{green}{g} = h(\textcolor{magenta}{d -\ (2 -\ d)}) = h (2d -\ 2) \\ \implies g &= {h(2d -\ 2) \over 2} = h(d -\ 1) \end{align*}

Notice that the center of a pentagram contains a regular pentagon. This means that the ratio of its height to the side is equal to the ratio of the larger pentagon’s height to its side. This gives us enough information to deduce d:

\begin{align*} {\textcolor{red}{h} \over 2(\textcolor{brown}{2 -\ d})} &= {2\textcolor{red}{h} + \textcolor{green}{g} \over \textcolor{blue}{2}} = {2h + h(d-1) \over 2} = {h(1 + d) \over 2 } \\ 2h &= 2h(1 + d)(2 -\ d) \\ 1 &= (1 + d)(2 -\ d) = 2 -\ d + 2d -\ d^2 \\ 0 &= d^2 -\ d -\ 1 \end{align*}

The (positive) quantity satisfying this polynomial is the golden ratio φ. It is half the length of the diagonal, so the ratio of a diagonal to a side is also φ.

To make calculations easier, some conversions will be made to base φ, or phinary. If you are not familiar already with phinary, I have already written at length about it here.

To calculate the apothem, we can calculate the sagitta s and height l by similar triangles.

\begin{align*} &\textcolor{blue}{c \over a} = \textcolor{brown}{2 \over \phi} \\ l &= c + a = {2a \over \phi} + a = a{2 + \phi \over \phi} = a{12_\phi \over 10_\phi} = a{2\bar{1}0_\phi \over 10_\phi} = a(2\bar{1}_\phi) \\ s &= c -\ a = {2a \over \phi} -\ a = a{2 -\ \phi \over \phi} = a{\bar{1}2_\phi \over 10_\phi} = a{2\bar{3}0_\phi \over 10_\phi} = a(2\bar{3}_\phi) \end{align*}

Finally, the Pythagorean theorem tells us that the product of these quantities is 1, allowing us to calculate a.

\begin{align*} 1 &= c^2 -\ a^2 = (c + a)(c -\ a) = ls \\ &= a^2(2\bar{1}_\phi)(2\bar{3}_\phi) = a^2(4\bar{8}3_\phi) = a^2(\bar{4}7_\phi) = a^2(3.\bar{4}_\phi) \\ a^2 &= {1 \over 3.\bar{4}_\phi} \cdot {43_\phi \over 43_\phi} = {43_\phi \over [12]\bar{7}.[\bar{12}]_\phi} = {3 + 4\phi \over 5} \\ \implies l^2 &= a^2(2\bar{1}_\phi)^2 = {3 + 4\phi \over 5} \cdot (4\bar{4}1_\phi) = {3 + 4\phi \over 5} \cdot 5 = 3 + 4\phi \end{align*}

The last few steps in solving for a^2 are somewhat tricky. The conjugate of φ is \varphi^* = -{1 \over \varphi}. Since the digit in the φ-1 place value is negative, its conjugate has a positive value in the φ place value, i.e., 3.\bar{4}_{\varphi^*} = 43_\varphi. Multiplying a quadratic root by its conjugate produces an integer value, which means that the scary quantity [12]\bar{7}.[\bar{12}]_\varphi resolves cleanly to 5.

The division can also be done explicitly in phinary:

\begin{align*} {1 \over 3.\bar{4}_\varphi} &= {1 \over 0.\bar{1}3_\varphi} = {500_\varphi \over 5 (\bar{1}3_\varphi)} = {233_\varphi + (0 = \textcolor{red}{4\bar{4}}\bar{4}0_\varphi = \textcolor{red}{26\bar{2}}\bar{4}0_\varphi) \over 5 (\bar{1}3_\varphi)} \\ &= {\bar{2}60\bar{1}3_\varphi \over 5 (\bar{1}3_\varphi)} = {2001_\varphi \over 5} = {221_\varphi \over 5} = {43_\varphi \over 5} = {3 + 4\varphi \over 5} \end{align*}

The Remaining Solids

With the diagonal length and apothem of a regular pentagon in tow, the geometry of the final two solids may be explored.

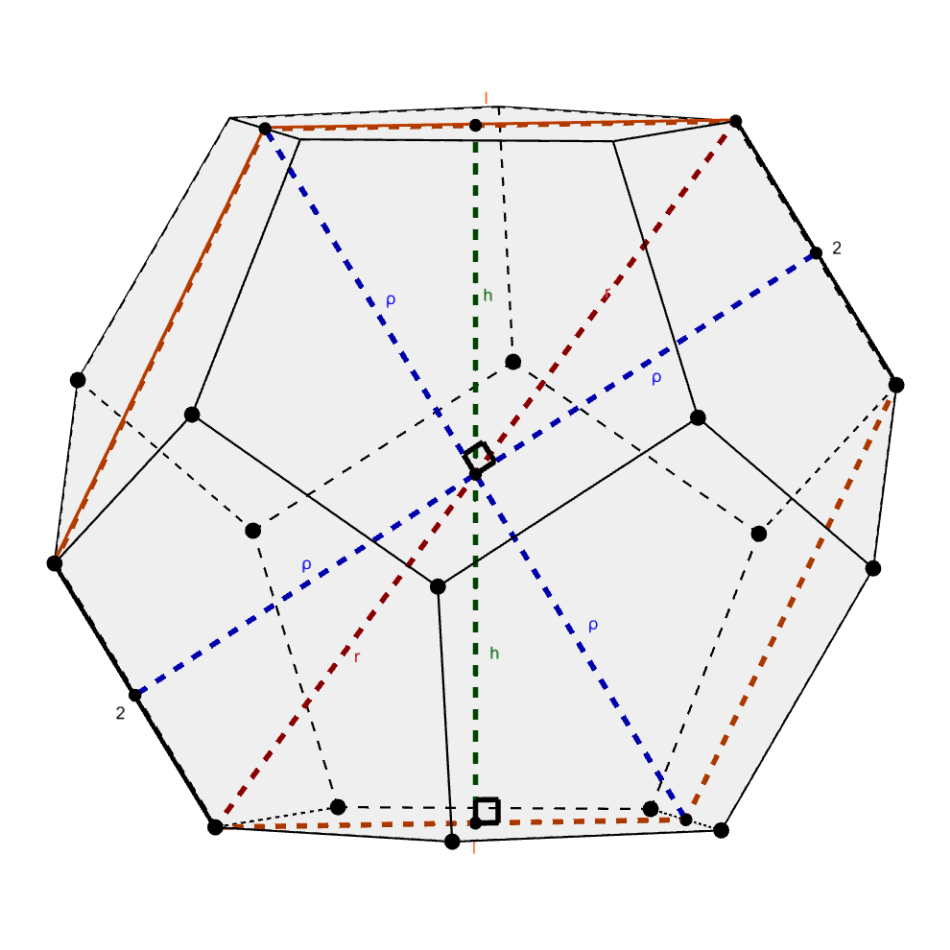

The icosahedron and dodecahedron are easiest to dissect as many pyramids joined to a single center. This is reminiscent of the area formula which uses the triangulation of a regular polygon its center.

The altitude (h) of any one pyramid is the radius of the insphere of the solid, which is tangent to the plane of every face. Similarly, the circumsphere (circumradius, r) contains all vertices, and the midsphere (midradius, ρ) is tangent to every edge. These will become important shortly.

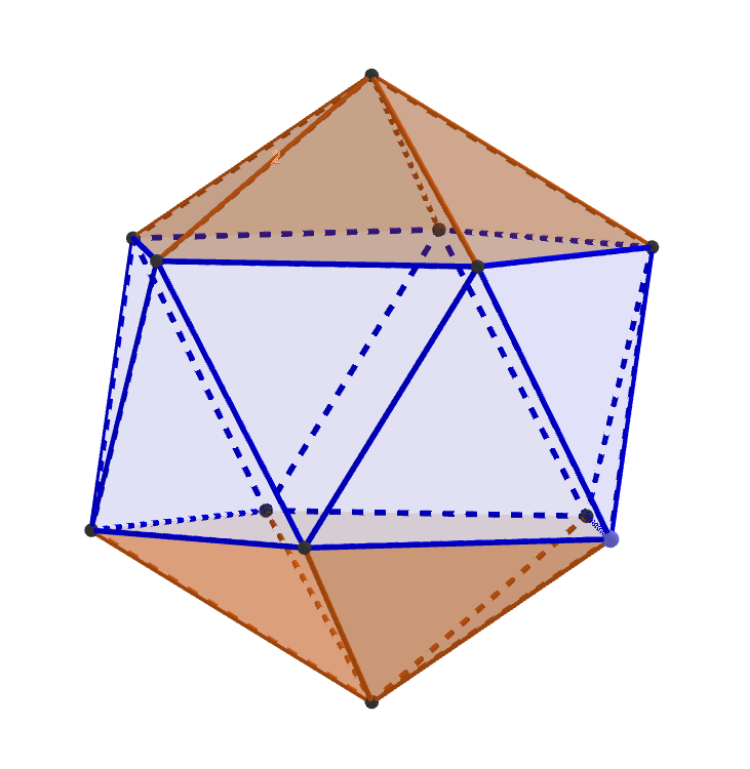

The Icosahedron: an Antiprism in Profile

The icosahedron can be decomposed into two pentagonal pyramids connected to either base of a pentagonal antiprism. An antiprism is a figure similar to a prism, but with the one of the bases twisted relative to the other and with (equilateral) triangles joining them.

The pentagonal antiprism may be bisected bisected along the plane containing the altitudes of two antipodal triangles. This forms a parallelogram with side lengths of the altitude of an equilateral triangle and height of a pentagon (l).

A segment connecting the centers of two antipodal faces is a diameter of the insphere (2h). This diameter can be translated along the parallelogram by a, the apothem of an equilateral trangle. This forms a right triangle with a and 2h as legs and l as the hypotenuse.

For an edge length of 2, we know from the tetrahedron that d_{altitude}^2 = (a + c)^2 = 3. From the above construction, (3a)^2 = 3 \implies a^2 = 1 / 3. So,

\begin{align*} (\textcolor{green}{2h})^2 &= \textcolor{red}{l}^2 - a^2 = \textcolor{red}{3 + 4\phi} -\ {1 \over 3} = {3(3 + 4\phi) -\ 1 \over 3} \\ h^2 &= {8 + 12\phi \over 3 \cdot 4} = {2 + 3\phi \over 3} = {32_\phi \over 3} \\ 32_\phi &= 210_\phi = 1100_\phi = 10000_\phi = \phi^4 \end{align*}

With the inradius in tow, we can calculate the volume of the icosahedron.

\begin{align*} (2^3 \cdot V_\text{ico})^2 &= \left ( 20 \cdot {Bh \over 3} \right )^2 = {20^2 B^2 h^2 \over 3^2} = {5^2 \cdot 4^2 \cdot 3 \cdot {\phi^4 \over 3} \over 3^2} = {5^2 \cdot 2^4 \cdot \phi^4 \over 3^2} \\ V_\text{ico}^2 &= {5^2 \cdot 2^4 \cdot \phi^4 \over 2^6 \cdot 3^2} = {5^2 \cdot \phi^4 \over 2^2 \cdot 3^2} \\ V_\text{ico} &= {5 \phi^2 \over 6} \end{align*}

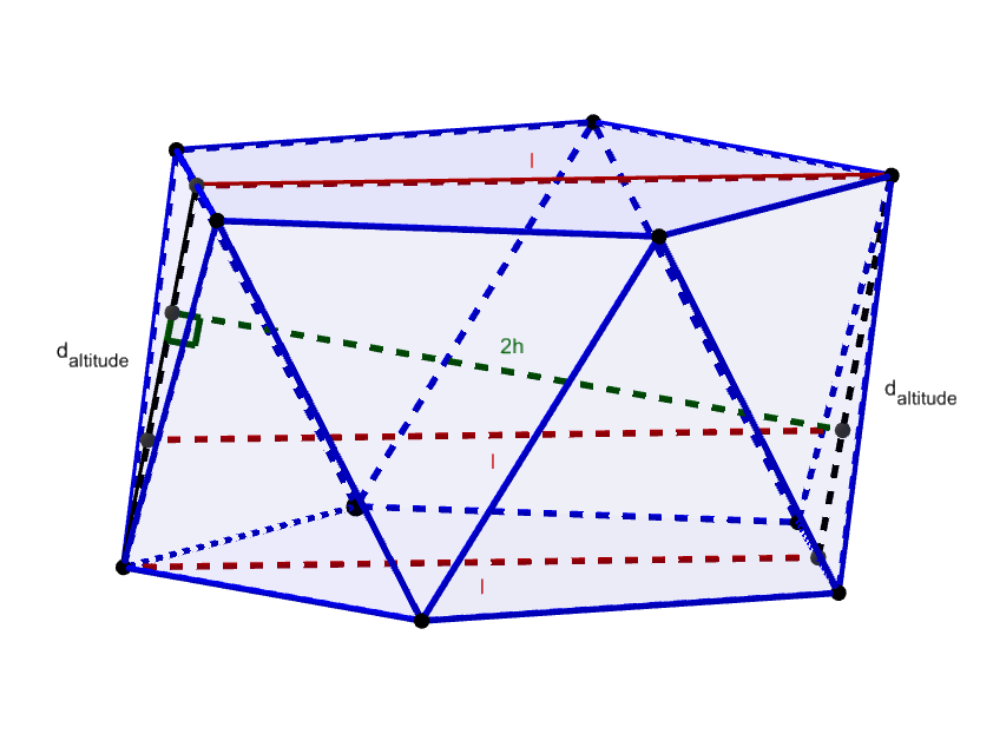

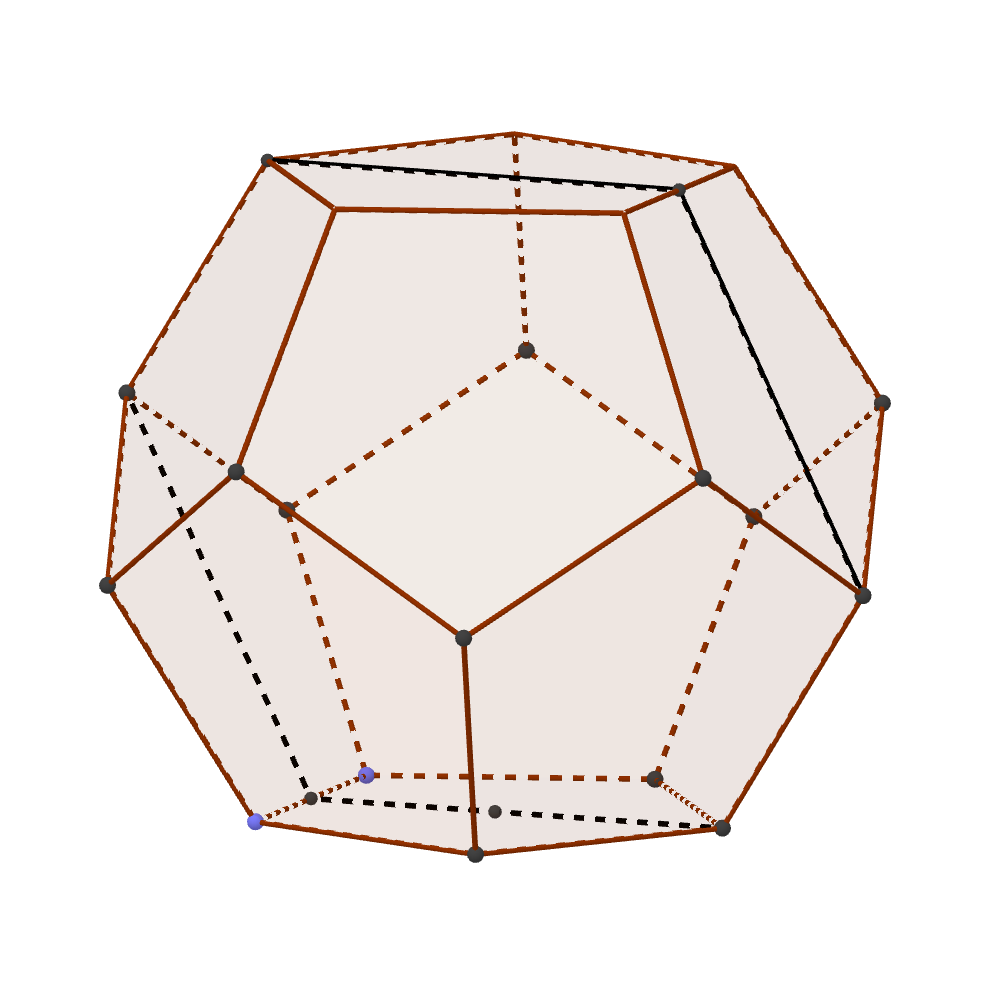

The Dodecahedron

The dodecahedron is a bit trickier. It belongs to a class of polyhedra known as truncated trapezohedra.

The bisection trick from the icosahedron mostly still works. Begin by bisecting the solid through antipodal altitudes. This produces an oblong hexagon made up of four pentagon heights and two edges.

The segment connecting the antipodal midpoints bisects the hexagon into two (isosceles) trapezoids, and is a diameter of the midsphere. It is parallel to the two edges, so dropping an altitude from this edge to the diameter produces a midradius.

The inradius h is the altitude of a triangle formed by the length of a pentagon (its base), a midradius, and a circumradius. The inradius meets the pentagon at its center, so we can use its apothem to relate the inradius and midradius.

a^2 + \textcolor{green}{h}^2 = \textcolor{blue}{\rho}^2

From the trapezoid, we know that the altitude with respect to the midradius is another midradius. This means that the height can be found by equating areas.

\begin{align*} \textcolor{orange}{l}\textcolor{green}{h} &= \textcolor{blue}{\rho \rho} \implies \textcolor{orange}{l}^2\textcolor{green}{h}^2 = (\textcolor{orange}{(2\bar{1}_\phi) a})^2 h^2 = 5a^2h^2 = \textcolor{blue}{\rho}^4 \\ 5a^2h^2 &= (a^2 + h^2)^2 = a^4 + 2a^2h^2 + h^4 \end{align*}

All terms in this polynomial are square, so we can solve for h in terms of a by completing the square. Note that x and y are auxiliary terms in this process.

\begin{align*} 0 &= h^4 -\ 3a^2h^2 + a^4 = (h^2 -\ x)^2 - y^2 \\ &= h^4 -\ 2xh^2 + x^2 - y^2 \\ -2x &= -3a^2 \implies x = {3a^2 \over 2} \\ x^2 - y^2 &= {9a^4 \over 4} - y^2 = a^4 \\ \implies y^2 &= {9a^4 \over 4} - {4a^4 \over 4} = {5a^4 \over 4} = {(2\bar{1}_\phi)^2 a^4 \over 4} = \left ( {(2\bar{1}_\phi) a^2 \over 2} \right )^2 \\ \\ h^2 -\ {3a^2 \over 2} &= y = {(2\bar{1}_\phi) a^2 \over 2} \\ h^2 &= {(2\bar{1}_\phi) a^2 \over 2} + {3a^2 \over 2} = {(22_\phi) a^2 \over 2} = (11_\phi) a^2 \\ &= {(11_\phi)(43_\phi) \over 5} = {473_\phi \over 5} = {[11]7_\phi \over 5} = {7 + 11\phi \over 5} \end{align*}

With the square of the inradius known, all that is left to do is find the volume.

\begin{align*} B^2 &= \left( {Pa \over 2} \right)^2 = (5a)^2 = 25a^2 = 5(43_\phi) \\ 5h^2 &= [11]7_\phi = 740_\phi = 4300_\phi = (43_\phi)(100_\phi) \\ (2^3 \cdot V_\text{dodec})^2 &= \left (12 \cdot {Bh \over 3} \right )^2 = 4^2 B^2 h^2 = 2^4 \cdot 5(43_\phi) \cdot {(43_\phi)(100_\phi) \over 5} \\ V_\text{dodec}^2 &= {2^4 \cdot (43_\phi)^2 \cdot (100_\phi) \over 2^6} = {(43_\phi)^2(10_\phi)^2 \over 2^2} \\ V_\text{dodec} &= {(43_\phi)(10_\phi) \over 2} = {(430_\phi) \over 2} = {(74_\phi) \over 2} = {4 + 7\phi \over 2} \end{align*}

Closing

Since each of these volumes has been calculated algebraically, there have been no approximate decimal forms. Ordered by size, the volumes of each of the solids are:

| Solid | Volume | Approximation | Length of Side with Unit Volume |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetrahedron | {1 \over 6\sqrt 2} | 0.1178511302… | 2.039648903… |

| Octahedron | {\sqrt{2} \over 3} | 0.4714045208… | 1.284898293… |

| Cube | 1^3 | 1 | 1 |

| Icosahedron | {5\phi^2 \over 6} | 2.181694991… | 0.7710253465… |

| Dodecahedron | {4 + 7\phi \over 2} | 7.663118961… | 0.5072220724… |

The dodecahedron being so much larger than the icosahedron surprised me, to be honest. When one glances at a set of dice (as one does), it seems like the d20 is larger than the d12, albeit with smaller edges. However, at least in one of my sets, the edges of the d20 are in fact about 1.5 times as long as those of the d12, implying their volumes are roughly equal (which would be handy for a manufacturer).

I tried to use as much coordinate-free geometry as I could in producing these diagrams. GeoGebra lacks a tool for producing Platonic solids other than cubes and tetrahedra, so I ended up cheating in coordinates for the octahedron and icosahedron diagrams.

On the other hand, the hexagon I described in the dodecahedron is of such importance to its construction that I ended up constructing it from scratch. I am rather proud of this because I did so without looking up someone else’s. After having written this post, I feel much more competent with compass-and-straightedge constructions.

All diagrams made with GeoGebra.

Footnotes

Though this is a pure mathematical concept, empirical units use the same convention. For instance, a cubic centimeter is defined as the volume occupied by a cube which is a centimeter long in each dimension, despite being applicable to volumes of any shape.↩︎