-- Equivalent to `a -> b`

type Exponent a b = (->) a bType Algebra and You, Part 2: A Fixer-upper

Broadening arithmetic to exponentials and adding in fixed points.

In the previous post, I wrote mostly about finite types, as well as type addition (Either) and multiplication ((,)) between them.

I mentioned at the end of the previous post that exponents correspond to functions. This post will focus on this operation before moving on to recursively-defined types.

Exponent Laws

It’s not a stretch to say that without them, nothing would get done in a program. They are denoted as:

\text{Exp}(X,Y) := Y^X = X \rightarrow Y

The arrow constructor (typically infixed) appears everywhere in Haskell types. But is the corresponding notation Y^X fitting or merely illusory?

Exponentiation Distributes over Multiplication

One law of exponents states that if we have a product raise it to an exponent, then the exponent should distribute to both terms. In types, this is:

\stackrel{ \text{A function to a product} }{Z \rightarrow (X \times Y)} = (X\times Y)^{Z} % \stackrel{?}{\cong} X^Z \times Y^Z = \stackrel{ \text{A pair of functions with a common input} }{(Z \rightarrow X) \times (Z \rightarrow Y)}

This says that a function f returning a pair can be decomposed as a pair of functions g and h returning each component. If we wish to convert form the former to the latter, we can call f, then use the functions that give either element of the tuple (fst and snd). Conversely, if we instead have a pair of functions from the same type, then we can just send the same value to both and put it in a pair.

undistExp :: (a -> b, a -> c) -> (a -> (b, c))

undistExp (g, h) x = (g x, h x)

-- undistExp (g, h) = \x -> (g x, h x)

distExp :: (a -> (b, c)) -> (a -> b, a -> c)

distExp f = (fst . f, snd . f)

-- distExp f = (\x -> fst (f x), \x -> snd (f x))

instance Isomorphism (Exponent a b, Exponent a c) (Exponent a (b, c)) where

toA = distExp

toB = undistExp

identityA = distExp . undistExp

identityB = undistExp . distExpUnlike with the sum and product, the identities here exist on functions themselves. Fortunately, Haskell is referentially transparent, so we could deepen the proof by composing the functions and using lambda calculus rules until the expression is clearly an identity. If we wanted to, it would be possible to do the same for the identities on the previous post. In the interest of being concise, I won’t be doing so.

Product of Exponents is an Exponent of a Sum

We also know that if two expressions with same base are multiplied, their exponents should add. So at the type level, we must check the equivalence of the following:

\stackrel{ \text{A pair of functions with a common return} }{(X \rightarrow Z) \times (Y \rightarrow Z)} = Z^{X} \times Z^Y % \stackrel{?}{\cong} Z^{X + Y} = \stackrel{ \text{A function on a sum} }{(X + Y) \rightarrow Z}

This says that a pair of functions g and h with the same return type can be composed into a function f. If we start with the former, we must create a function f on Either which decides which function to use. If we have this function already, we can get back to where we started by putting our values into Either with Left or Right before using f. The bijections look like:

toExpSum :: (a -> c, b -> c) -> (Either a b -> c)

toExpSum (g, h) w = case w of

Left x -> g x

Right y -> h y

-- toExpSum (g, h) = \w -> case w of ...

fromExpSum :: (Either a b -> c) -> (a -> c, b -> c)

fromExpSum f = (f . Left, f . Right)

-- fromExpSum f = (\x -> f (Left x), \y -> f (Right y))

instance Isomorphism (Exponent a c, Exponent b c) (Exponent (Either a b) c) where

toA = fromExpSum

toB = toExpSum

identityA = fromExpSum . toExpSum

identityB = toExpSum . fromExpSumThis identity actually tells us something very important regarding the definition of functions on sum types: they must have as many definitions (i.e., a product of definitions) as there are types in the sum. This has been an implicit part of all bijections involving Either, since they have a path for both Left and Right.

Exponent of an Exponent is an Exponent of a Product

Finally (arguably as consequence of the first law), if we raise a term with an exponent to another exponent, the exponents should multiply.

\stackrel{ \text{A function returning a function} }{X \rightarrow (Y \rightarrow Z)} = (Z^{Y})^X % \stackrel{?}{\cong} Z^{X \times Y} = \stackrel{ \text{A function on a product} }{(X \times Y) \rightarrow Z}

We start with a function which returns a function and end up with a function from a product. The equivalence of these two types is currying, an important concept in computer science. Haskell treats it so importantly that the bijections are almost trivial

curry' :: (a -> (b -> c)) -> ((a, b) -> c)

curry' f (x, y) = f x y

-- curry' f = \(x, y) -> (f x) y

uncurry' :: ((a, b) -> c) -> (a -> b -> c)

uncurry' f x y = f (x, y)

-- uncurry' f = \x -> \y -> f (x, y)

instance Isomorphism (Exponent a (Exponent b c)) (Exponent (a,b) c) where

toA = uncurry'

toB = curry'

identityA = uncurry' . curry'

identityB = curry' . uncurry'These come pre-implemented in Haskell since tuples are harder to define than a chain of arrows.

Double-Checking for Algebra

Even though we’ve established that sums, products, and exponents obey their normal arithmetical rules, we’ve yet to lay the groundwork for algebra. In algebra, we start by introducing a symbol called x and allow it to interacting with numbers. This means that it obeys the arithmetical laws that have been established.

Functors allow us to parametrize a type in a similar way to this. We already know how to add and multiply finite types, for a “variable” type X, it bears checking that it can add and multiply with itself.

Coefficients

Is it truly the case that an object’s sum with itself is its product with a 2-valued type? It should follow from addition laws, but it might behoove us to check

type LeftRight a = Either a a

-- Alternatively:

-- type LeftRight a ≅ (Bool, a)X + X \stackrel{?}\cong 2 \times X

It’s actually quite simple if we look back at the implementation of Bool as Either () (). False values go on the Left, and True values go on the Right:

to2Coeff :: LeftRight a -> (Bool, a)

to2Coeff (Left x) = (False, x)

to2Coeff (Right x) = (True, x)

from2Coeff :: (Bool, a) -> LeftRight a

from2Coeff (False, x) = Left x

from2Coeff (True, x) = Right x

instance Isomorphism (LeftRight a) (Bool, a) where

toA = from2Coeff

toB = to2Coeff

identityA = from2Coeff . to2Coeff

identityB = to2Coeff . from2CoeffWe can continue adding X to itself using Either to obtain arbitrarily high coefficients. This is simplest as Either a (Either a (... (Either a a))), where values are a chain of Rights ending in a Left. Then, the maximum number of Rights allowed is n - 1. Counting zero, there are n values, demonstrating the type n.

Exponents

Multiplying X by a finite type is all well and good, but we should also check that it can multiply like itself. If all is well, then this should be equivalent to raising X to an exponent. We’ve already discussed those laws, but just in case, we should check

type Pair a = (a, a)

-- Pair a ≅ (Bool -> a)X \times X \stackrel{?}{\cong} X^2 = 2 \rightarrow X

To wit, we express the pair as a function from the finite type Bool. If we have our pair of X, then we know our output is one of the two, and return a function that decides to return. On the other hand, we need only apply a function from Bool to every possible value in Bool as many times as it appears (twice) and collect it in a product to get back to where we started. The bijections to and from this type look like this

to2Exp :: (a, a) -> (Bool -> a)

to2Exp (x, y) False = x

to2Exp (x, y) True = y

-- to2Exp (x, y) = \p -> case p of ...

from2Exp :: (Bool -> a) -> (a, a)

from2Exp f = (f False, f True)

instance Isomorphism (a, a) (Bool -> a) where

toA = from2Exp

toB = to2Exp

identityA = from2Exp . to2Exp

identityB = to2Exp . from2ExpThis a special case of what are called representable functors. The functor in question is Pair, represented by functions from Bool. A similar argument can be shown for any n that \overbrace{X \times X \times ... \times X}^n can be represented functions from n.

Together, these two isomorphisms mean that any polynomial whose coefficients are positive integers can be interpreted as a functor in X.

Fixing What Ain’t Broke

Exponents, finite types and polynomials are wonderful, but we need to go further. Even though we have access to types for any natural number, we can only define finite arithmetic within them. We could inflate the number of possible values in a naive way…

data Nat = Zero | One | Two | Three | Four | Five | ...\begin{matrix} & \scriptsize \text{Zero} & \scriptsize \text{or} & \scriptsize \text{One} & \scriptsize \text{or} & \scriptsize \text{Two} & \scriptsize \text{or} \\ X =& 1 &+& 1 &+& 1 &+& ... \end{matrix}

…but this is akin to programming without knowing how to use loops. In Haskell, we approach (potentially infinite) loops recursively. One of the simplest ways we can recurse is by using a fixed-point combinator. While typically discussed at the value level as a higher-order function, there also exists a similar object at the type level which operates on functors. Haskell implements this type in Data.Fix, from which I have copied the definition below

-- Fix :: (* -> *) -> *

newtype Fix f = In { out :: f (Fix f) }

-- Compare with the functional fixed-point

fix :: (a -> a) -> a

fix f = let x = f x in x\mathcal{Y}(F(X)) := F(\mathcal Y (F))

(“Y” here comes from the Y-combinator, which isn’t entirely accurate, but is fitting enough)

If we Fix a functor f Values of this type are the functor f containing a Fix f. In other words, it produces a new type containing itself.

Au Naturale

To demonstrate how this extends what the kinds of types we can define, let’s work out the natural numbers. Peano arithmetic gives them a recursive definition: they are either 0 or the successor of another natural number. The “naive” definition in Haskell is very simple. Arithmetically, though, things seem to go wrong.

data Nat' = Zero | Succ Nat'

zero' = Zero

one' = Succ Zero

two' = Succ one'

-- ...Values in Nat' are a string of Succs which terminate in a Zero. Of course, we also could define this in terms of Fix. First, we need to define a type to fix, then apply the operator

data NatU a = ZeroU | SuccU a

-- Possible values are "In ZeroU" or "In (SuccU (x :: Fix NatU))"

type NatF = Fix NatUIf we look at things a little closer, we realize that NatU has the exact same form as the successor functor, Maybe.

type Nat = Fix Maybe

zero = In Nothing

one = In (Just zero)

two = In (Just one)

-- ...\text{Nat} \text{ or } \omega := \mathcal Y(S)

Looking back, the statement X = 1 + X is identical to the statement “X is the fixed point of the successor”, as its definition implies. Using the latter form, we can define a bijection to and from Int (which I’m regarding as only containing positive integers) as

toNat :: Int -> Nat

toNat 0 = In Nothing

toNat x = In $ Just $ toNat $ x - 1 -- the successor Nat of the predecessor of x

fromNat :: Nat -> Int

fromNat (In Nothing) = 0

fromNat (In (Just x)) = 1 + fromNat x -- ...of the predecessor of In (Just x)

instance Isomorphism Int Nat where

toA = fromNat

toB = toNat

identityA = fromNat . toNat -- Valid for positive integers only!

identityB = toNat . fromNatThese bijections are different from the ones we have seen thus far. Both of them are defined recursively, just like our functorial Fix. Consequently, rather than exhausting the possible cases, it relies on deconstructing Nats and arithmetic on Ints.

succNat :: Nat -> Nat

succNat x = In (Just x)

-- succNat x = In . Just

succInt :: Int -> Int

succInt x = x + 1There’s actually no way to know whether the functions above do the same thing, at least without knowing more about Int. At best, they afford us a way to bootstrap a way to display numbers that isn’t iterated Justs.

Functors from Bifunctors

If the first argument of a bifunctor is fixed, then what remains is a functor. For example, with Either:

forall a. Either a :: * -> *Since this type is functor-like, we can apply Fix to it.

type Any a = Fix (Either a)

-- Any' a ~ (Either a (Any' a))

leftmost x = In (Left x)

oneRight x = In (Right (leftmost x))

twoRight x = In (Right (oneRight x))\text{Any}(X) := \mathcal Y(E(X,-)) = \mathcal Y(X +)

Remember what was said earlier about types which look like nested Either a? This type encompasses all of those (granted, interspersed with the Fix constructor).

I used the names “one” and “two” in the above example functions to suggest similarity to Nat above. In fact, if a ~ (), then because we already our functor Either () is isomorphic to Maybe, we know that Any () is isomorphic to Nat. If the type was Any Bool, We could terminate the chains in either Left True or Left False; it is isomorphic to (Nat, Bool). In general, Any a is isomorphic to (Nat, a).

toAny :: (Nat, a) -> Any a

toAny (In Nothing, x) = In (Left x)

toAny (In (Just n), x) = In (Right (toAny (n, x)))

fromAny :: Any a -> (Nat, a)

fromAny = fromAny' (In Nothing) where

fromAny' x (In (Left y)) = (x, y)

fromAny' x (In (Right y)) = fromAny' (In (Just x)) y

instance Isomorphism (Nat, a) (Any a) where

toA = fromAny

toB = toAny

identityA = fromAny . toAny

identityB = toAny . fromAnyNote how fixing a sum-like object gives a product-like object.

What about Products?

If we can do it for sums, we should be able to do it for products. However, unlike sums, products don’t have a builtin exit point. For Either, all we need to do is turn Left and be done, but fixing a product goes on endlessly.

type Stream a = Fix ((,) a)

-- Stream a ~ (a, Stream a)

repeatS x = In (x, repeatS x)

-- = In (x, In (x, ...\text{Stream}(X) := \mathcal Y(P(X,-)) = \mathcal Y(X \times)

Unlike Void, whose “definition” would require an infinite chain of constructors, we can actually create values of this type, as seen above with the definition of repeatS. Fortunately, Haskell is lazy and doesn’t actually try to evaluate the entire result.

If fixing a sum produced a product object with a natural number, then it stands to reason that fixing a product will produce an exponential object with a natural number. By this token, we should try to verify that \text{Stream}(X) \cong X^{\omega} = \text{Nat} \rightarrow X. Intuitively, we have an value of type X at every position of a stream defined by a natural number (the input type). This specifies every possible position.

toStream :: (Nat -> a) -> Stream a

toStream f = toStream' (In Nothing) where

toStream' n = In (f n, toStream' (In (Just n)))

fromStream :: Stream a -> (Nat -> a)

fromStream (In (x,y)) (In Nothing) = x

fromStream (In (x,y)) (In (Just m)) = fromStream y m

-- fromStream (In (x,y)) = \n -> case n of ...

instance Isomorphism (Nat -> a) (Stream a) where

toA = fromStream

toB = toStream

identityA = fromStream . toStream

identityB = toStream . fromStreamNotice that in toStream, an equal number of “layers” are added to Nat and Stream with the In constructor, and in fromStream, an equal number of layers are peeled away.

As you might be able to guess, analogously to Bool functions representing Pairs, this means that Streams are represented by functions from Nat.

And Exponents?

Fixing exponents is a bad idea. For one, we’d need to pick a direction to fix since exponentiation, even on types, is obviously non-commutative. Let’s choose to fix the destination, just to match with the left-to-right writing order.

-- Haskell is perfectly willing to let you declare this as a type

type NoHalt a = Fix ((->) a)\text {NoHalt}(X) := \mathcal Y((-)^X) = \mathcal Y(X \rightarrow)

There is no final destination since it gets destroyed by Fix. If we regard functions as computations, this is one that never finishes (hence the name NoHalt). Haskell always wants functions to have a return type, so this suggests the type is unpopulated like Void.

Closing

Function types are one of the reasons Haskell (and functional programming) is so powerful, and fixed-point types allow for recursive data structures. Functions on these structures are recursive, which are dangerous since they can generate paradoxes:

void = fix V :: Void -- old

neverend = fix (id :: Void -> Void) -- new

infinity = fix succNat :: Nat

neverend' = fix (id :: Nat -> Nat)In practice, were any of these values actually present and strict computation were performed on them, the program would never halt. The absurd function the older Data.Void demonstrates this. The newer version merely raises an exception and obviates giving Void a constructor altogether (though it still has an id).

Since we are now posed to look at polynomials as types and generate potentially infinite types, the next post will feature a heavy, perhaps surprising focus on algebra.

An Extra Note about Categories

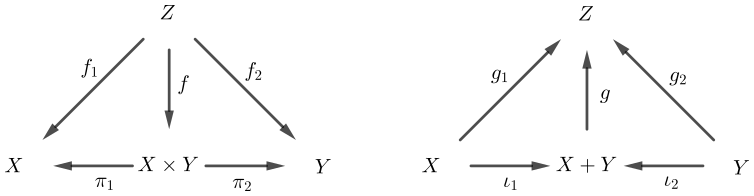

Category theory is a complex and abstract field (that I myself struggle to apprehend) which is difficult to recommend to total novices. I would, however, like to point out something interesting regarding its definition of product and coproduct (sum).

In these diagrams, following arrows in one way should be equivalent to following arrows in another way. If you recall the exponential laws and rewrite them in their arrowed form, this definition makes a bit more sense.

\begin{gather*} \begin{matrix} \stackrel{f \vphantom{1 \over 2}}{(X \times Y)^{Z}} \vphantom{} \cong \vphantom{} \stackrel{f_1 \times f_2 \vphantom{1 \over 2}}{X^Z \times Y^Z} \\[0.5em] f: Z \rightarrow(X \times Y) \\[0.5em] f_1: Z \rightarrow X \\[0.5em] f_2: Z \rightarrow Y \\[0.5em] \pi_1,\pi_2= \tt fst, snd \end{matrix} && \begin{matrix} \stackrel{g_1\times g_2 \vphantom{1 \over 2}}{Z^{X} \times Z^Y} \vphantom{} \cong \vphantom{} \stackrel{g \vphantom{1 \over 2}}{Z^{X + Y}} \\[0.5em] g: (X+Y) \rightarrow Z \\[0.5em] g_1:X \rightarrow Z \\[0.5em] g_2: Y \rightarrow Z \\[0.5em] \iota_1,\iota_2 = \tt Left, Right \end{matrix} \end{gather*}

Category theory is more general, since morphisms (function arrows) need not correspond to objects (types) in the category. The (pseudo-)category in which Haskell types live is “cartesian closed”, meaning that products and exponential objects exist. This lets more general categories maintain their flexibility, but seems like an arbitrary distinction without mentioning counterexamples.

Additional Links

- Representable Functors (from Bartosz Milewski’s Categories for Programmers)

- An interesting note at the end of this article mentions an interesting formal manipulation: a functor F(X) is represented by \log_X( F(X) )