12 Pentagons, Part 1

There are 12 pentagons. How many hexagons can there be?

Recently I’ve been trying my hand at a little 3D geometry. I was watching a lecture on YouTube where the presenter asks the following (paraphrased) as an exercise:

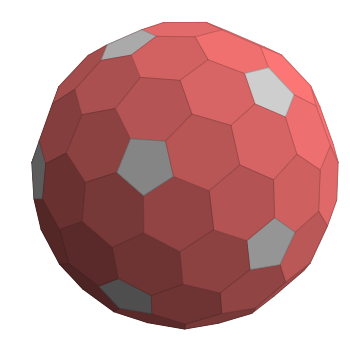

A soccer ball is a (roughly spherical) figure made of pentagons and hexagons, each meeting 3 at a point. Prove that there are 12 pentagons. If you want to explore this problem further: how many hexagons can there be?

Why 12? Why Hexagons?

Before counting hexagons, there are a couple of things that we should understand about the problem. For example, if we’re interested in fixing the number of pentagons, are hexagons somehow special? Does this explain why are there 12 pentagons?

3D figures in general have three things we can count: vertices, edges and faces. We are further interested in counting two different kinds of faces. In the original statement of the problem, these are pentagons and hexagons, but to understand why hexagons are important, we should consider pentagons and n-gons instead.

Since the figure’s shape is roughly spherical, like a soccer ball, its Euler characteristic is 2:

\chi = V - E + F = V - E + F_5 + F_n = 2

Another constraint given in the problem is that all faces meet with three at a vertex. This is actually the minimal case – if all of the faces on a polyhedron are convex, then there must be at least three that meet at a vertex (else one of the two faces sharing an edge contains an angle greater than 180 degrees).

This means that:

- An edge always ends in a pair of vertices, so counting edges double-counts vertices

- A vertex always joins three edges, so counting vertices triple-counts edges

- An n-face has n vertices and edges, so counting faces n-counts vertices and edges

More succinctly, these conditions can be written as:

3V = 2E = 5F_5 + nF_n

Exactly 12

This gives us three equations in five unknowns, which is a little daunting. First, let’s clear the equation for the Euler characteristic of E and F_n.

\begin{align*} \chi &= V - E + F_5 + F_n \\ 2n\chi &= 2nV - \textcolor{red}{2nE} + 2nF_5 + 2nF_n + \textcolor{blue}{0}\\ &= 2nV - \textcolor{red}{\stackrel{3V = 2E}{3nV}} + 2nF_5 + 2nF_n + \textcolor{blue}{\stackrel{3V = 5F_5 + nF_n}{ 6V - 10F_5 - 2nF_n }} \\ &= (6 - n)V + (2n - 10)F_5 \\ &= 4n \end{align*}

In this form, the simplest cases of the problem become obvious:

- n = 5, and there are only pentagons

- V(6 - 5) + F_5(2(5) - 10) = V = 4(5) = 20

- In this case, all occurrences of F_n above turn out to be 0, since all of the pentagons are counted by F_5

- n = 6, and the non-pentagons are hexagons

- V(6 - 6) + F_5(2(6) - 10) = 2F_5 = 4(6) = 24

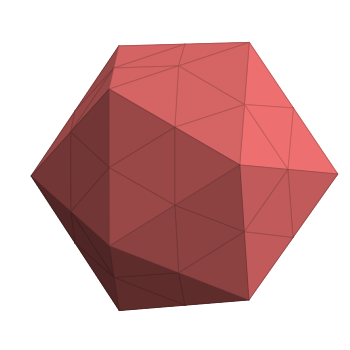

Thus, by asserting that the figure is composed of pentagons and hexagons, the figure must contain exactly 12 pentagons. This is the case even if there are no hexagons, in which case we are describing a dodecahedron (which, incidentally, has 20 vertices).

Consequently, we get an expression for the number of vertices and edges in terms of the number of hexagons.

- 3V = 6F_6 + 5 F_5 = 6F_6 + 60 = 3V \implies V = 2F_6 + 20

- 2V = 6F_6 + 5 F_5 \implies E = 3F_6 + 30

Duality

It’s convenient not only to think of our target figures with pentagons and hexagons, but their duals. In the equation for the Euler characteristic, vertices and faces have the same sign. This (correctly) suggests that we can construct a new figure by replacing all faces with a vertex and vice versa.

At the level of equations, this means that

3F' = 2E' = 5V_5' + 6V_6'

Or in other words, all the faces in the dual figure are triangles (3F' = 2E') and vertices either join 5 or 6 edges (2E' = 5V_5' + 6V_6'). We can also think of dualization as a process which transforms our vertices into triangles, pentagonal faces into degree-5 vertices and hexagonal faces into degree-6 ones.

Increasing Specificity

If we know there are 12 pentagons, then the number of hexagons is the only free parameter, since it was eliminated from the earlier equation.

Perhaps we could produce a new equation by counting more precisely. Each edge comes in 3 genera: it can either join 2 pentagons, 2 hexagons, or a pentagon and a hexagon each. Similarly, each vertex has 4 different arrangements: 3 pentagons, 2 pentagons and 1 hexagon, 1 pentagon and 2 hexagons, and 3 hexagons.

Counting only pentagons, only hexagons, and only each type of vertex gives:

\begin{gather*} 6F_6 = 3V^0 + 2V^1 + V^2 = 2E^0 + E^1 \\ 5F_5 = V^1 + 2V^2 + 3V^3 = E^1 + 2E^2 \end{gather*}

When these equations are added together, they reproduce the 3V = 2E relationship. But by adding 5 more unknowns, only a couple more equations have been added to the system, and no new information has been gained aside from the combinatorics of vertex and edge configurations. A solution for the number of hexagons must be realized by other means.

An Argument from Symmetry

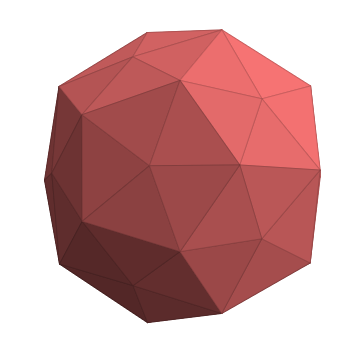

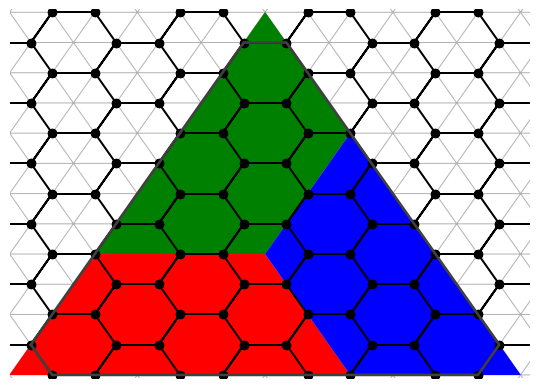

Having established that there are 12 pentagons, and that the base case is a dodecahedron, what next?

Well, we know that dodecahedrons have icosahedral symmetry. In the most naive way, we can realize this by by placing a regular pentagon (of a suitable size and orientation) at each of the 12 vertices of the icosahedron. If the pentagons touch one another, this is again just a dodecahedron. However, if the pentagons are small, then we can fit equilateral hexagons in between them. This has three properties:

- Each pentagon is transitive, or equivalent to other pentagons in terms of the way hexagons are connected to it.

- Since each pentagon is regular, it is invariant under fifths of a turn.

- Each triple of “adjacent” pentagons (which we’ll call a “sector”) is rotationally symmetric under thirds of a turn, as in the rotation of a dodecahedron around a vertex. This also must be the case for hexagons in the sector.

This formulation results in what is known as the Goldberg-Coxeter construction, and the resultant polyhedra are known as Goldberg polyhedra.

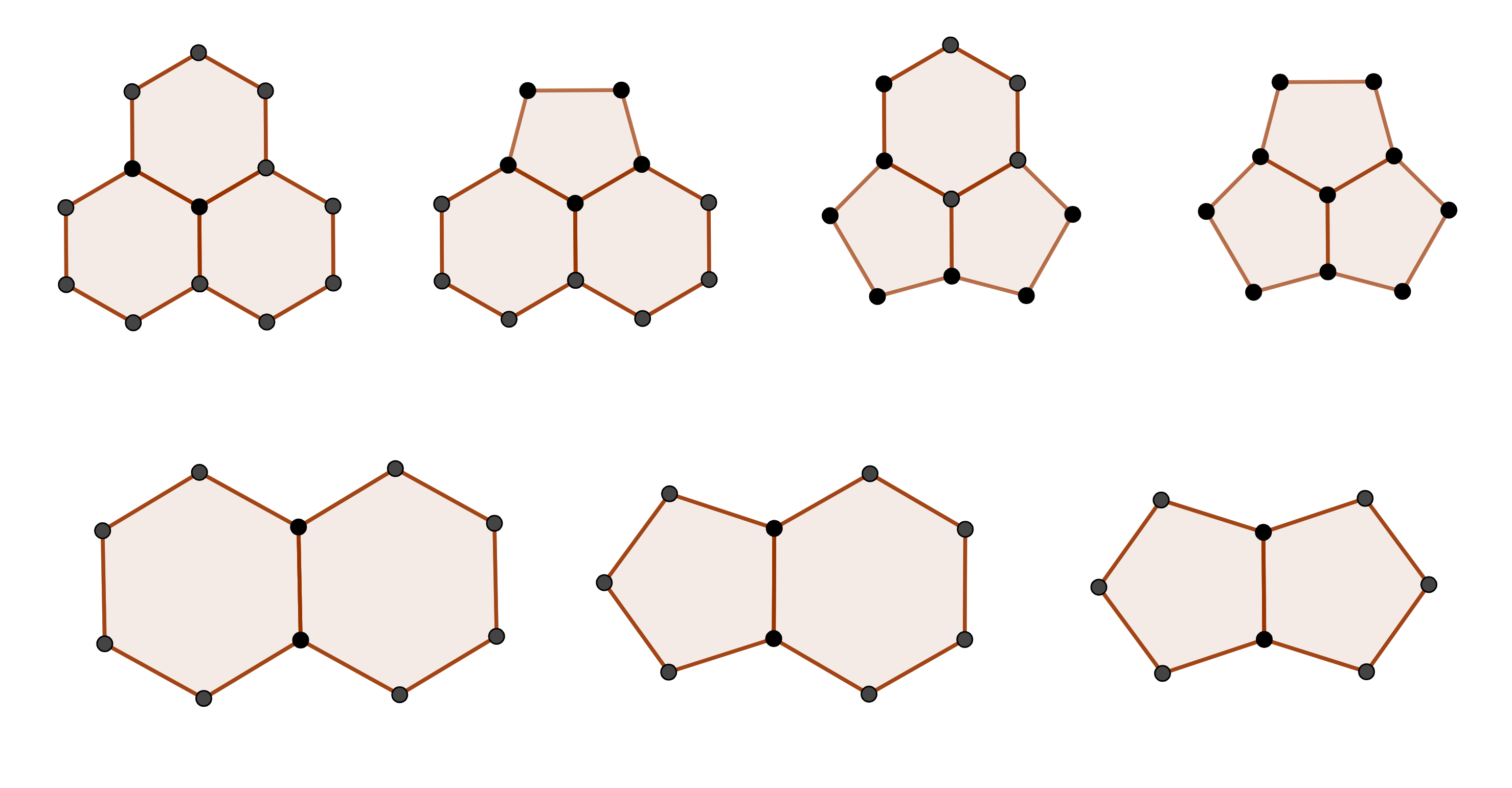

Triangles and Honeycombs

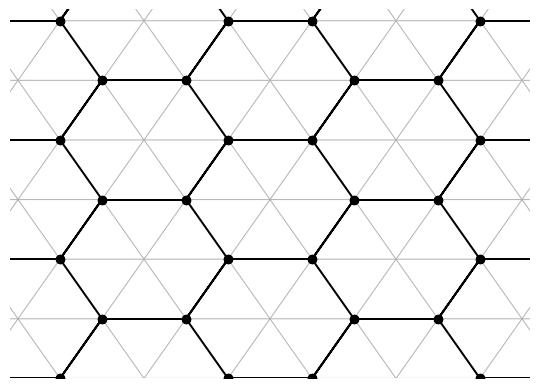

The hexagons in our target figures cannot be regular. By the vertex condition, each hexagon must meet with three at a point, and regular hexagons in such an arrangement tessellate the plane like a honeycomb.

A plane is exactly what we want, though. As mentioned above, each sector must transform like a triangle under rotation. It therefore makes sense to work on a triangle grid and identify hexagons on it.

Note also that the triangular grid is dual to the hexagonal one.

In this grid, the lower-left triangle is not part of a hexagon, and instead comes from one of the pentagons in the figure. For every pentagon in the figure, there are five copies of the grid, with the lower-left triangle in each overlapping slightly. This means that the partial hexagons at one of the edges of the grid will always be complemented by the other edge, always giving full hexagons.

Each point in the grid is of the form a + bu, where u is the complex root of x^2 - x + 1, which satisfies u^6 = 1 (a primitive sixth root of unity). Since 1 and u are not perpendicular like 1 and i, the norm is not simply a^2 + b^2. We can find its norm by multiplying by its conjugate, which is a + b u^5.

\begin{gather*} \| a + bu \| = (a + bu)(a + bu^5) = a^2 + (u + u^5)ab + b^2 \\ \\ u^5 = u \textcolor{red}{u^2 u^2} = u\textcolor{red}{(u - 1)(u - 1)} \\ = \textcolor{blue}{(u^2 - u)}(u - 1) = \textcolor{blue}{(-1)}(u - 1) = -u + 1 \\ \\ \| a + bu \| = a^2 + ab + b^2 \end{gather*}

Hooray, we get a simple (and symmetric) polynomial in a and b! This symmetry is apparent in the grid, since the grid is laterally symmetric about a line cutting it in half. Flipping along this line exchanges the axes for a and b, so a and b must be interchangeable.

Counting Triangles

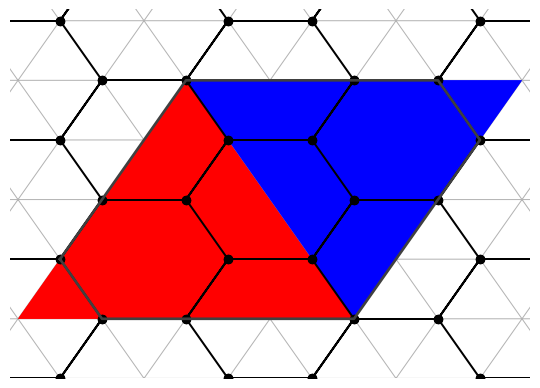

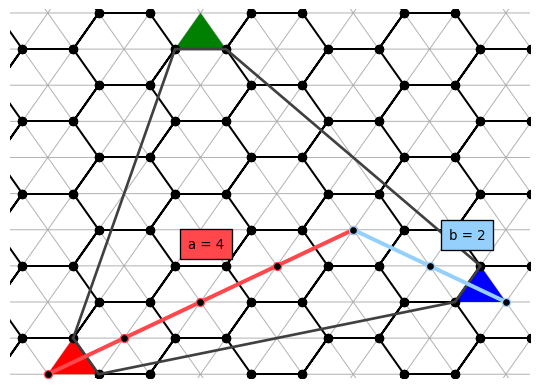

Each point a + bu = (a, b) has an secondary interpretation: we can use it to parametrize a path between two pentagonal faces. On the target figure, if we start from any pentagon facing an edge, we walk across a edges onto the center of hexagons. Then, we turn to face an adjacent edge, then walk across b edges onto another pentagon, completing the walk.

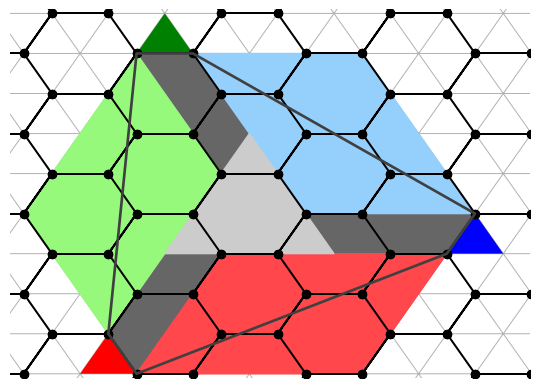

Paths between pentagons corresponding to (4, 2) and (2, 4). The gray outline shows the sector.

It turns out that the (triangular) norm of the path directly corresponds to the number of triangles unique to each sector. Geometrically, there are three classes.

Class I

These are points of the form (a, 0) (or symmetrically, (0, a)).

Two sectors are shown in the above diagram, with each sector composed of a large triangle. The large triangles are bounded by a triangles, and contain a^2 triangles. Coincidentally, \|(a, 0)\| = a^2.

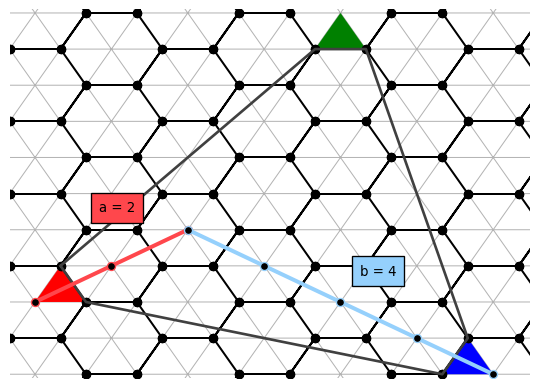

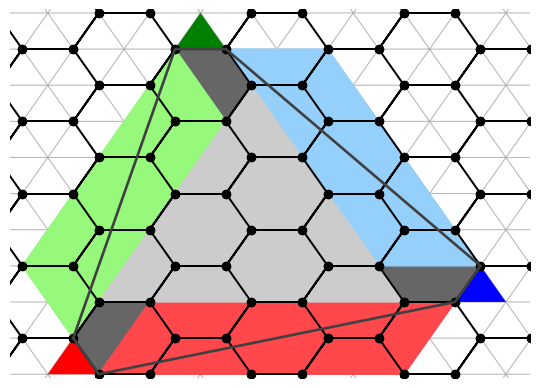

Class II

These are points of the form (a, a).

In the above diagram, we split a sector into three trapezoids, one for each pentagon. This makes it obvious that the largest triangle is bounded by 3a triangles and therefore has 9a^2 triangles in it.

Each pentagon therefore gets 3a^2 triangles, and \|(a, a)\| = 3a^2.

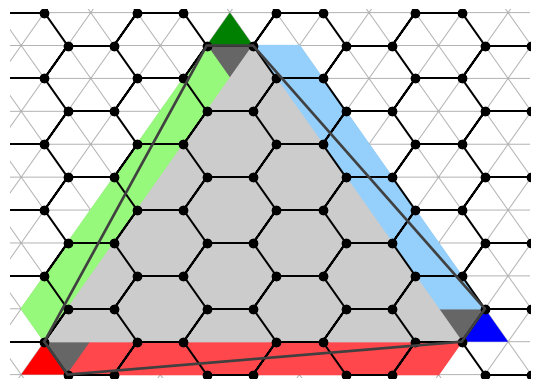

Class III

These are all remaining points of the form (a, b). It should go without saying that this is the most complicated case.

In each case we do not cleanly slice the plane. The largest triangle which can fit in the sector is colored in light gray. This shape is surrounded by three parallelograms.

By inspection, it seems like the central triangle is bounded by 3, 6, and 9 triangles, or generally 3b. Similarly, the parallelograms are have heights 3, 2, and 1 (generally, a - b) and widths 5, 7, and 9 (generally, a + 2b - 1).

A more careful calculation

We can verify this by calculating the coordinates of the blue triangle. Starting from the red triangle, designate the lower-left vertex to be (0, 0). After taking a steps, we are at (a, a), which is the center of a hexagon. The hexagon we face after turning clockwise is centered (a, a) + (2, -1). After b steps, the vertex of the blue triangle which is not touching a hexagon lies at (a, a) + (2b, -b) = (a + 2b, a - b). Now, from that vertex, move one vertex to the left and draw a diagonal to the (0, 0) This line is a diagonal of a parallelogram with width a + 2b - 1 and height a - b.

Finally, notice that the central triangle does not have the same width as the parallelogram, since the height of another parallelogram (minus the one colored triangle) is in the way. This means that it is bounded by a + 2b - 1 - (a - b - 1) = 3b triangles.Now, a parallelogram of height w and width h is what remains after building a large triangle of width w + h and removing two a large triangles: one of width w from the top and one of width h from the side. Thus, a parallelogram contains (w + h)^2 - w^2 - h^2 = 2wh triangles,

We can finally count the number of triangles:

\begin{align*} T &= 3wh + (3b)^2 = 3(a + 2b - 1)(a - b) + 9b^2 \\[4pt] &= 3(a^2 + 2ab - a - ab - 2b^2 + b) + 9b^2 \\[4pt] &= 3a^2 + 3ab + (9 - 6)b^2 + (6 - 6)a - (6 - 6)b \\[4pt] &= 3a^2 + 3ab + 3b^2 = 3\|a + bu\| \end{align*}

Giving an equal share of triangles to each pentagon as before, each has \|a + bu\| triangles.

Triangles to Hexagons

From this, we can very easily compute the number of hexagons. One of the triangles belongs to the pentagon and should not be counted, but the rest belong to hexagons. Hexagons are composed of 6 triangles, so point (a, b) counts \|a +bu\| - 1 \over 6 hexagons.

There are this many hexagons for each edge of a pentagon, so there are:

\begin{gather*} {\|a + bu\| - 1 \over 6} \scriptsize {\text{hexagons} \over \text{edge}} \normalsize \cdot 5 \scriptsize {\text{edges} \over \text{pentagon}} \normalsize \cdot 12 \scriptsize \text{ pentagons} \normalsize \\[4pt] = 10(\|a + bu\| - 1) \text{ hexagons} \end{gather*}

In other words, the number of hexagons is 10 times a number of the form a^2 + ab + b^2 - 1, for integers a and b.

It may seem strange that the result is an integer, since every pentagonal sector contains at least some partial hexagons. However, all of these partial hexagons are completed on the adjacent sectors. You can try visualizing this by placing each sector on the face of an icosahedron (the dual of the dodecahedron).

Beyond Soccer Balls

The three cases of paths as described above are also used to delineate classes of Goldberg polyhedra. Only class I and II polyhedra produce figures which are mirror-symmetric (I_h, which contains I). Class III polyhedra lack this; they come in chiral pairs due to the choice of a clockwise turn in their construction.

Basic Conway Operators

Before listing certain Goldberg polyhedra, I will comment on their relationship to Conway polyhedron notation. Given a “seed” polyhedron and a string of operators (applied right-to-left), many polyhedra can be constructed. The simplest seed polyhedra are the Platonic solids (their symbols enclosed in parentheses): the (T)etrahedron, (C)ube, (O)ctahedron, (D)odecahedron, and (I)cosahedron.

List of Operators

Roughly, 6 operators generate most Goldberg polyhedra:

- Dual (d)

- Swaps faces for vertices and vice versa. Involutory.

- Kis (k_n)

- Replaces each face with a pyramid.

- If n is specified, only applies to n-gonal faces.

- Truncate (t_n = dk_nd)

- Expands a vertex into a face, with the number of sides equalling the degree of the vertex.

- If n is specified, only applies to vertices of degree n.

- Subdivide (u_n)

- For polyhedra with triangular faces, divides each into n^2 triangles by cutting each edge into n parts.

- For unspecified n, n = 2.

- Chamfer (c = dud)

- Adds hexagonal faces along edges, preserving existing vertices and faces.

- Whirl (w)

- Rotates faces outward and interpolates with hexagonal faces along each edge.

- Higher order whirls are possible, but outside the scope of this post.

The last three operations are obtained from the Goldberg-Coxeter construction, and as such, are termed Goldberg-Coxeter operators. Both chamfer and whirl add hexagons, meaning they transform Goldberg polyhedra into other Goldberg polyhedra. Also, since every vertex in a Goldberg polyhedron has degree 3, it is always possible to use odd u operators by taking the dual.

Two compound operators which also produce Goldberg polyhedra from existing ones are:

- dk = d(dtd) = td

- Raises pentagons and expands hexagons (as in gnomons of centered hexagonal numbers).

- Changes class I polyhedra into class II and vice versa.

- (dk)^2 = dkdk = tk

- Preserves class.

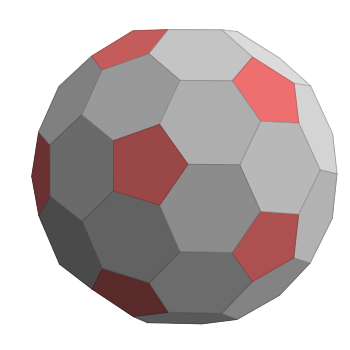

List of Hexagon Counts

Here is a list containing the number of hexagons in each Goldberg polyhedron, answering the initial question. Though this list can be found elsewhere, I’ll duplicate the first few entries here.

| Class | Parameter | F_6 | E | V | Conway |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a, b) | 10 T - 10 | 30 T | 20 T | ||

| I | (1, 0) | 0 | 30 | 20 | D |

| (2, 0) | 30 | 120 | 80 | dudD = cD | |

| (3, 0) | 80 | 270 | 180 | du_3dD = tkD | |

| (4, 0) | 150 | 480 | 320 | du_4dD = ccD | |

| (5, 0) | 240 | 750 | 500 | du_5dD | |

| II | (1, 1) | 20 | 90 | 60 | dkD |

| (2, 2) | 110 | 360 | 240 | dkdudD = dkcD | |

| (3, 3) | 260 | 810 | 540 | dkdu_3dD = dktkD | |

| III | (2, 1) | 60 | 210 | 140 | wD |

| (3, 1) | 120 | 390 | 260 | * | |

| (3, 2) | 180 | 570 | 380 | * | |

| (4, 1) | 200 | 630 | 420 | wdkD |

T = a^2 + ab + b^2

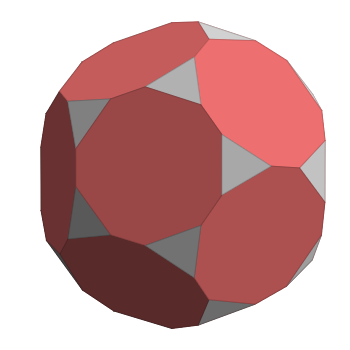

The polyhedron which corresponds to the shape of a soccer ball has parameter (1, 1). It is known (as implied by its Conway notation) as the truncated icosahedron. Similarly to how the entry (1, 0) is special because the dodecahedron is a Platonic solid, (1, 1) is special in that it is an Archimedean solid. This means that every vertex has the same configuration: 2 hexagons and 1 pentagon (V = V^1).

The Class I and Class II solutions are fairly generalizable. Class I solutions can be achieved dualizing subdivisions. Class II solutions can be generated from Class I solutions by applying an additional dk.

The Class III solutions are not. The whirl operator is fairly special, corresponding directly to the (2, 1) case. The norm of this parameter is 7, which is prime. Similarly, the entries with missing recipes, (3, 1) and (3, 2), have norms of 13 and 19, both of which are prime. Consequently, they do not have operators associated to them. On the other hand, (4, 1) has a norm of 21, which can be factored into 3 and 7 – these correspond to the operators dk and w, respectively.

Closing

Goldberg polyhedra on their own are fascinating because they can be found in nature. Buckyballs can be formed according to their structure, with number of carbons equalling the number of vertices. Viral capsids are frequently observed to be arranged in these shapes. Goldberg’s original paper can be found here, which contains additional observations such as the non-uniqueness of hexagon counts to a particular tuple.

Despite the elegance in the symmetry and simple classification of these shapes, this does not produce every possible polyhedron as described by the problem statement. In the next few posts, I will do my best to catalogue additional, more obscure solutions.

Polyhedron images were generated using polyHédronisme and vertex enumeration image was created with GeoGebra.