12 Pentagons, Part 2

There are 12 pentagons. Why stop at dodecahedra?

This is the second part in an investigation into answering the following question:

A soccer ball is a (roughly spherical) figure made of pentagons and hexagons, each meeting 3 at a point. [T]here are 12 pentagons…how many hexagons can there be?

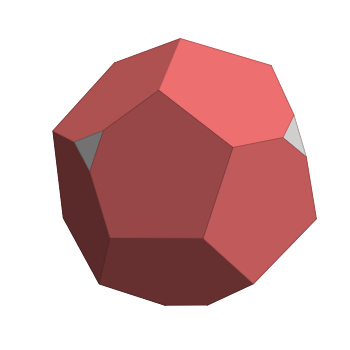

The post prior to this one proved the 12 pentagons portion as well as outlined an entire solution class: (dodecahedral) Goldberg polyhedra.

Despite these solutions being interesting in their own right, I grew preoccupied with finding other, more obscure solutions missed by this construction.

Twelve is Four Triples

A key characteristic of the solution polyhedra is that each vertex is of degree three (3V = 2E). It would be extraordinarily convenient if three pentagons came together at a vertex, or in the parlance of the previous post, a V^3. Since there are 12 pentagons, there must be four vertices.

Fortunately, there exists a Platonic solid with four vertices whose symmetries we can exploit: the tetrahedron.

Extended Goldberg Polyhedra

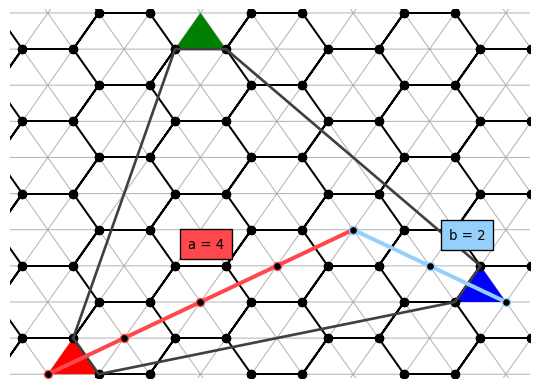

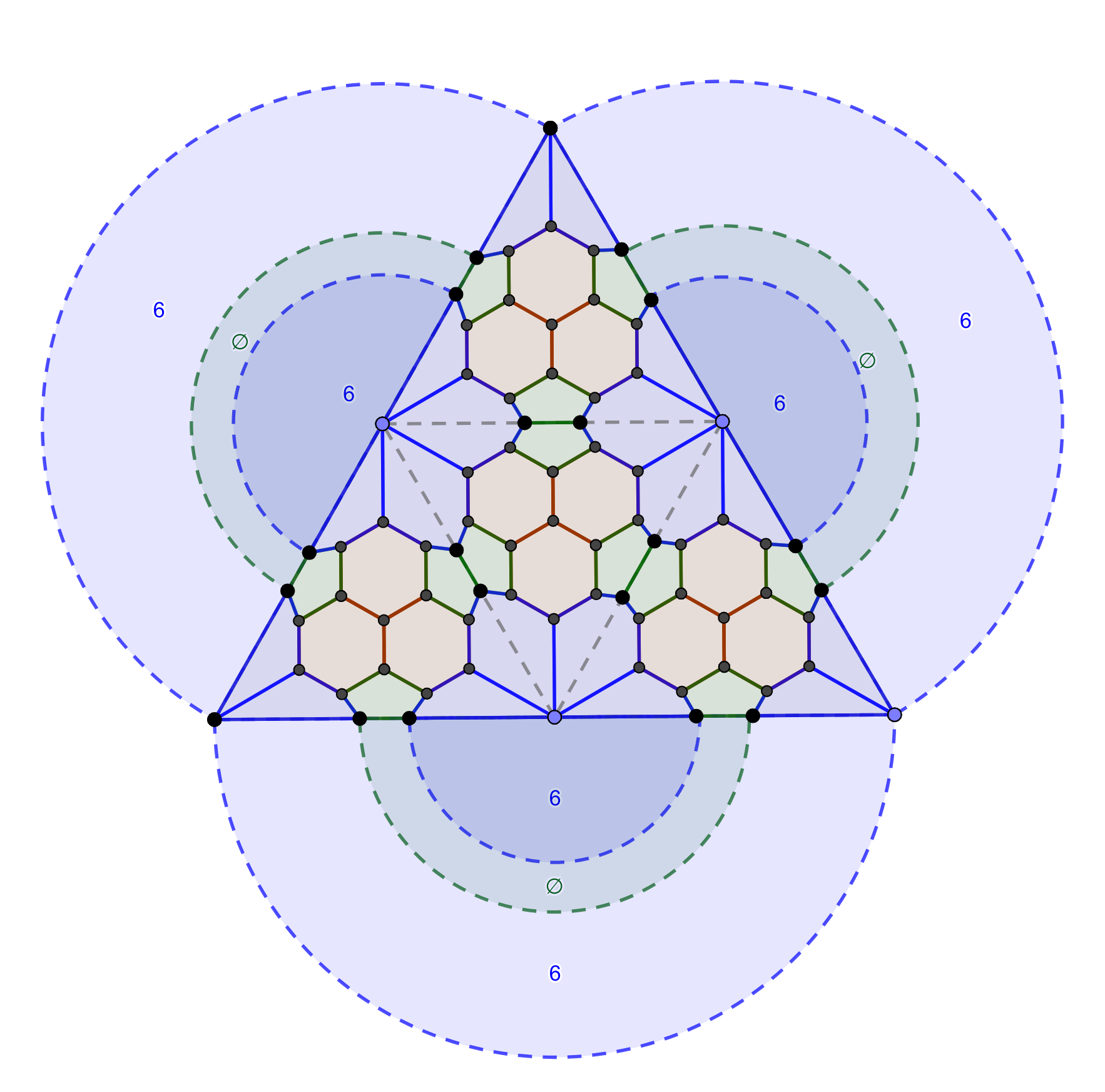

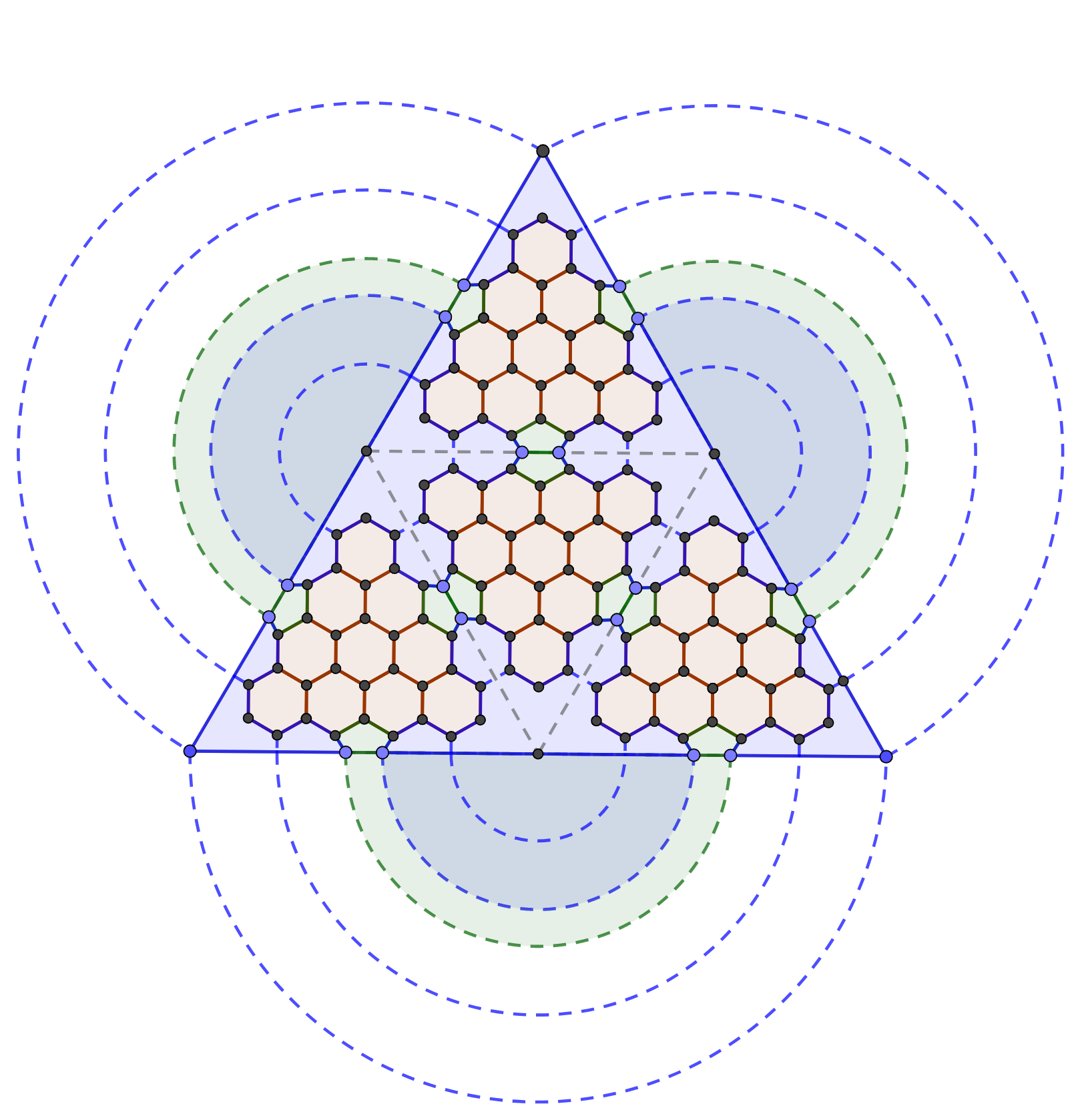

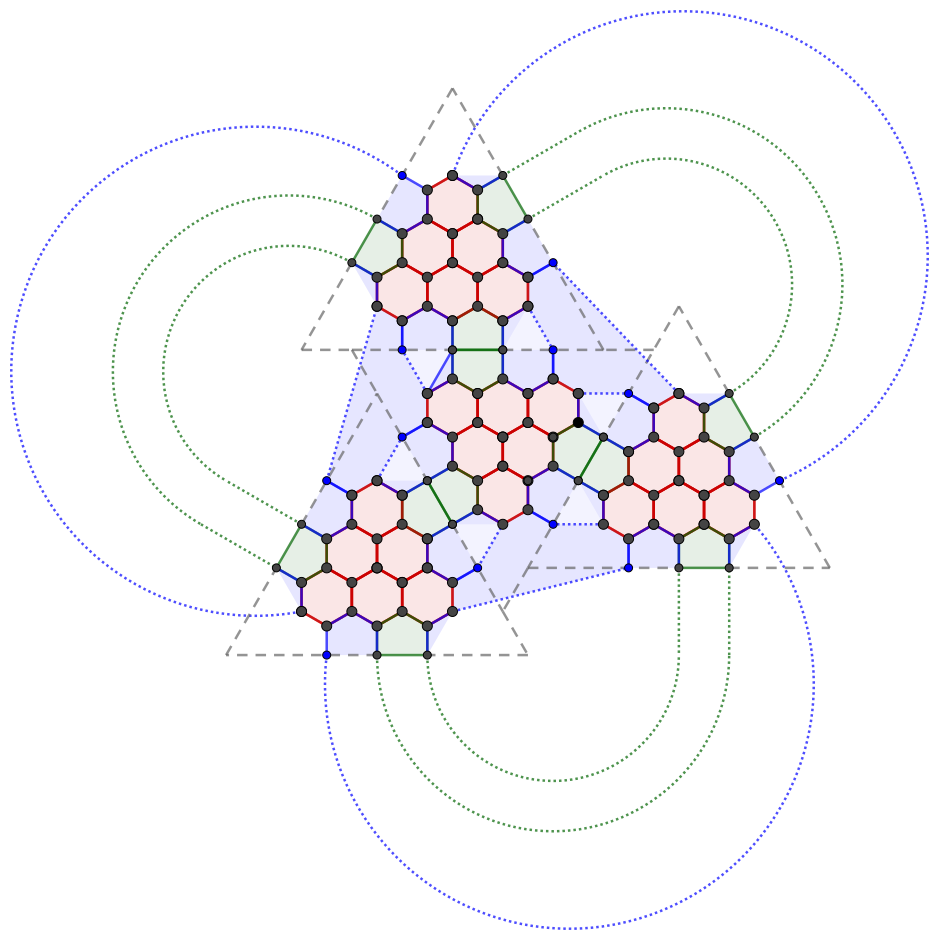

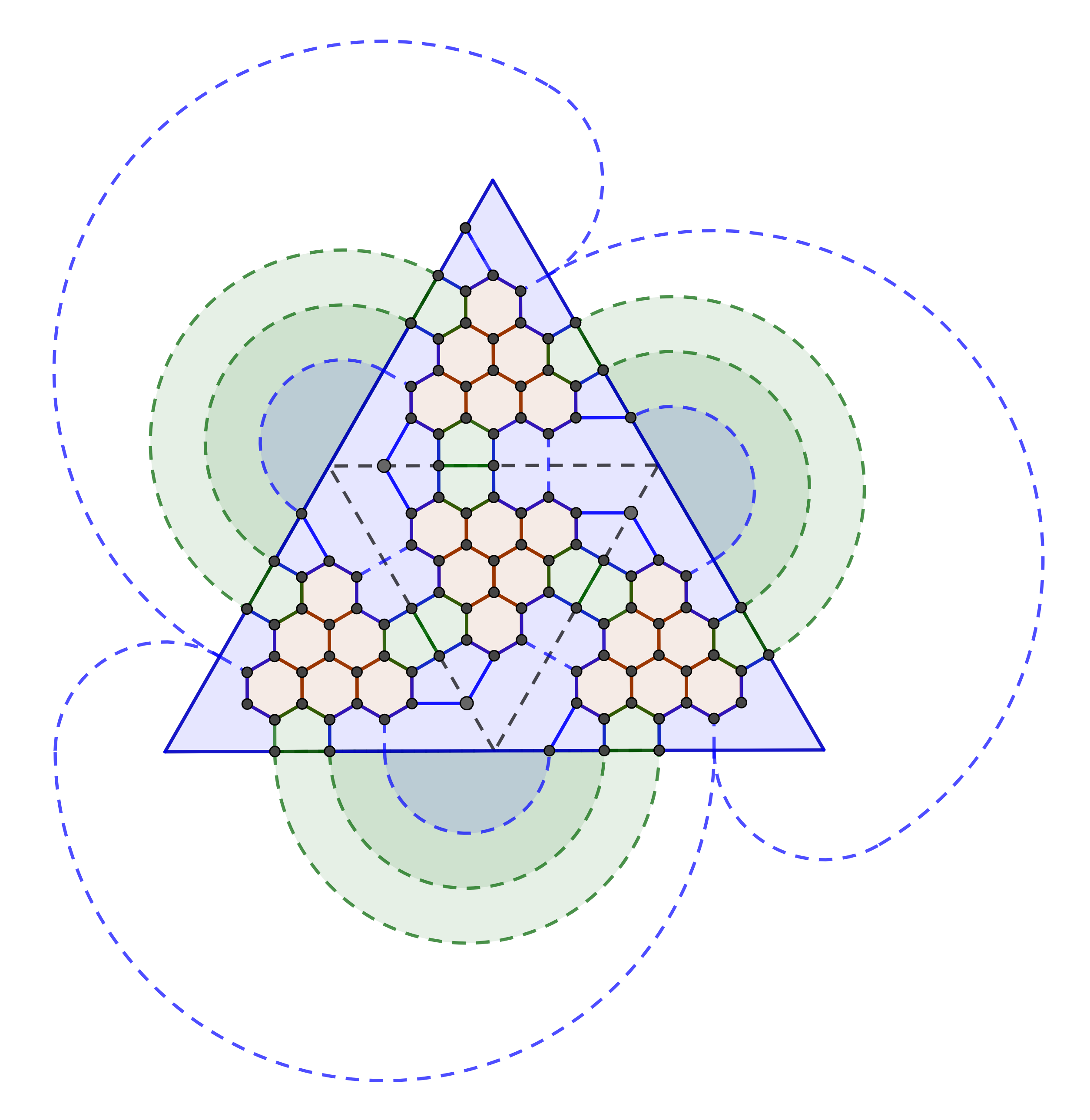

All vertices in the tetrahedron are of degree 3. This qualifies it to undergo Goldberg construction1. Recall the triangular plane and hexagonal paths from the previous part (presented again here for convenience):

When applying the construction to the dodecahedron, the red, green, and blue triangles were supposed to be part of a pentagon. Instead, the triangles can also be considered as whole triangles bordering a sector. Just like in the dodecahedral case, Class I polyhedra build hexagons in the shape of gnomons of centered hexagonal numbers, Class II polyhedra build them in the shape of triangular numbers, and Class III build them in the shape of figures with triangular symmetry.

Supposing a tetrahedron is made into a Goldberg polyhedron, where does that get us? Well for starters, we know there are:

\begin{gather*} {\|a + bu\|\ –\ 1 \over 6} \scriptsize {\text{hexagons} \over \text{sector}} \normalsize \cdot 3 \scriptsize {\text{sectors} \over \text{triangle}} \normalsize \cdot 4 \scriptsize \text{ triangles} \normalsize \\[4pt] = 2(\|a +bu\|\ –\ 1) \text{ hexagons} \end{gather*}

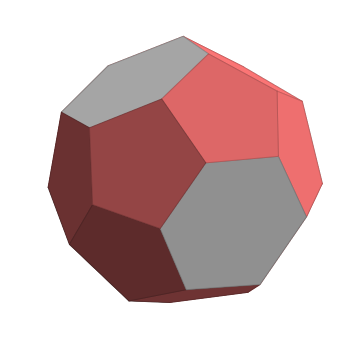

The figure produced by this construction also must have tetrahedral symmetry (T), since it was constructed from the tetrahedron. This symmetry occurs within icosahedral symmetry, which we’ve already explored.

To transform this figure into a true solution, recognize that each triangle shares an edge with 3 hexagons. If the triangle is “capped” such that all three adjacent faces are made to meet at a vertex, then the hexagons turn into pentagons. There are now 12 pentagons and 12 fewer hexagons than there were previously, or 2\|a +bu\|\ –\ 14.

This can be considered an opposite process to truncation, or “antitruncation”. Rather than selecting for the degree, this type of truncation selects for the vertex configuration: that of having three pentagons meeting at it (V^3).

Negative Hexagons?

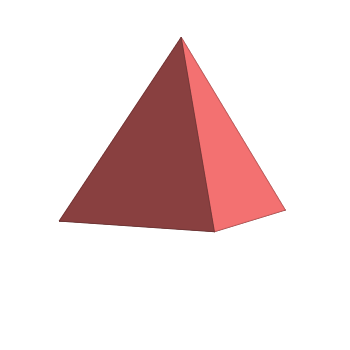

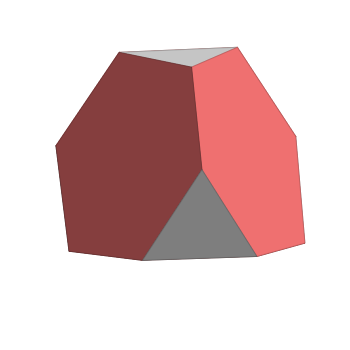

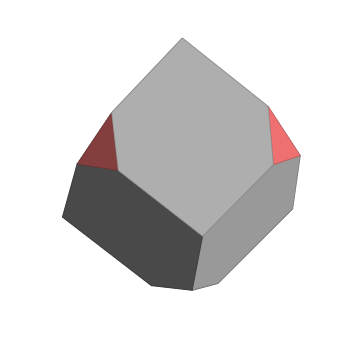

There is a slight problem with the above expression. The norms of (1, 0), (1, 1), (2, 0), and (2, 1) are all less than or equal to 7, which implies a negative number of hexagons. This is because the antitruncations correspond to one of the three Platonic solids with 3 faces to an vertex:

Antitruncation: dT = T

Antitruncation: T

Antitruncation: C

Antitruncation: D

With these exceptional cases taken care of, the table of solution polyhedra of this form is as follows:

| Class | Parameter | Conway (Trunc) | Conway | F_6 | V | E | Paths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | (1, 0) | T | dT | -12 | -4 | -6 | |

| (2, 0) | dudT = cT | C | -6 | 8 | 12 | ||

| (3, 0) | du_3dT = tkT | t_6kT | 4 | 28 | 42 | (1, 0) | |

| (4, 0) | du_4dT = ccT | t_6juT | 18 | 56 | 84 | (2, 0) | |

| (5, 0) | du_5dT | ** | 36 | 92 | 138 | (3, 0) | |

| (6, 0) | duu_3dT = ctkT | t_6kcT | 58 | 136 | 204 | (4, 0) | |

| II | (1, 1) | dkT | T | -8 | 4 | 6 | |

| (2, 2) | dkdudT = dkcT | t_6uT | 10 | 40 | 60 | (1, 1) | |

| (3, 3) | dkdu_3dT = dktkT | t_6ktT | 40 | 100 | 150 | (2, 2) | |

| (4, 4) | dkduudT = dkccT | t_6uuT | 82 | 184 | 276 | (3, 3) | |

| III | (2, 1) | wT | D | 0 | 20 | 30 | (1, 0) |

| (3, 1) | * | * | 12 | 44 | 66 | ||

| (3, 2) | * | * | 24 | 68 | 102 | ||

| (4, 1) | wdkT | t_6gtT | 28 | 76 | 114 | w(2, 1) | |

| (4, 2) | wcT | t_6guT = t_6gcT | 42 | 104 | 156 | (3, 1) |

** Unknown. Possibly nonexistent under standard operators

The operators g and j, which I did not introduce previously, appear in the above table. Rather than explaining their intuitive meaning, see the Wikipedia article instead.

Note also that the links in the above table may have recipes do not match their entry. Rather, the recipe is equivalent to the simpler string in the table to ensure the viewer can stably generate the output shape.

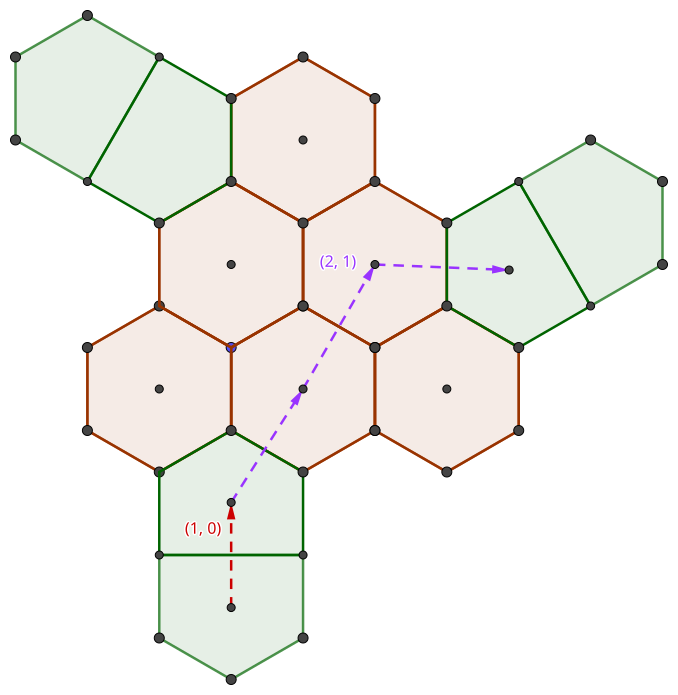

By leaving a pentagon from an edge which does not share a vertex with another pentagon, we can follow a path on the hexagons to another pentagon. In the Class I case, this crosses two fewer edges than the parameter, since the edges of the triangle from the Goldberg operation have been capped. This is also true in the Class II case, but both terms of the parameter are decreased by 1. Class III is mostly the same as Class II, except when one of the parameters is 1. In this case, the path is “whirled” – it approaches the terminal pentagon from an edge touching another pentagon. Also, for a whirled path w(a, b), both paths (a, b) and (a + b, 0) have this property.

The smallest “real” tetrahedral solution has 4 hexagonal faces. This is the (order-6) truncated triakis tetrahedron, which corresponds nicely with its Conway notation t_6kT.

Solution Non-Exclusivity

Is it possible for the number of hexagons in a tetrahedral Goldberg solutions to coincide with that of a dodecahedral Goldberg solutions? For this to be the case,

\begin{align*} \stackrel{\text{Tetrahedral}}{2\|m + nu\| - 14} &= \stackrel{\text{Dodecahedral}}{10\|a + bu\| - 10} , \text{ for } a, b, m, n \in \mathbb{Z} \\ \|m + nu\| - 2 &= 5\|a + bu\| \\ \|m + nu\| &\equiv 2\ (\text{mod } 5) \end{align*}

Class I parameters have a norm which is a square number, but 2 is not among the squares mod 5, so the tetrahedral solutions will never intersect dodecahedral solutions.

Tetrahedral Class II coincidences such as (2, 2) and (3, 3) seem more plausible, but this turns out to be a red herring. First, note that the norms on either side of the equation must be congruent to 0 or 1 (mod 3)2. In particular, \|m + mu\| is always congruent to 0 (mod 3) and 5\|a + bu\| is congruent to 0 or 2 (mod 3). But -2 is congruent to 1, so equality is impossible.

Only tetrahedral Class III collisions exist, and they must be congruent to the pairs (1, 2), (2, 1), (2, 2), (3, 3), (3, 4), or (4, 3) (mod 5). Some of these can be found in the table below.

| Dodecahedral Parameter | Tetrahedral Parameter | F_6 |

|---|---|---|

| (1, 0) | (2, 1) | 0 |

| (2, 1) | (4, 3) | 60 |

| (3, 1) | (7, 2) | 120 |

| (3, 2) | (8, 3) | 180 |

| (5, 0) | (7, 6) | 240 |

| (5, 1) | (12, 1) | 300 |

| (6, 1) | (9, 8) (13, 3) |

420 |

| (5, 3) (7, 0) |

(11, 7) (14, 3) |

480 |

| (5, 4) | (17, 1) | 600 |

| (7, 2) | (13, 8) | 660 |

Twelve is Six Pairs

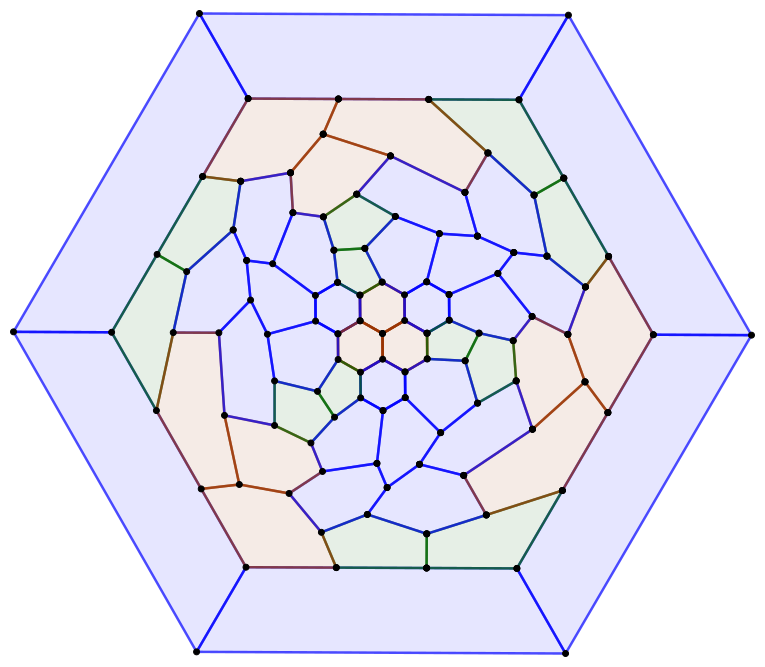

The truncated triakis tetrahedron (for simplicity, TTT) also reveals another possible set of solution polyhedra. It not only has four V^3s – which are produced by the antitruncation – but also six E^2s. These edges align with the six edges of the original tetrahedron. Unfortunately, selectively preserving these edges by using standard Conway operators is difficult, and the only recourse is to develop solutions by hand.

Hexagons in Triangles

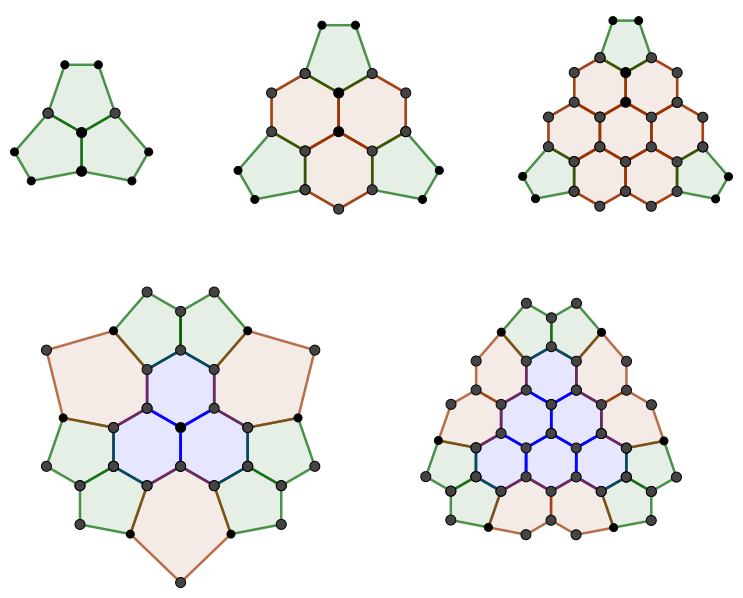

It is easiest to see solutions take form on a tetrahedral net. Every face and every vertex of a tetrahedron must be invariant under thirds of a turn, so when we interpolate with hexagons, the shape they form near those regions must be symmetric in the same way. The easiest way to do this is by arranging hexagons in triangles.

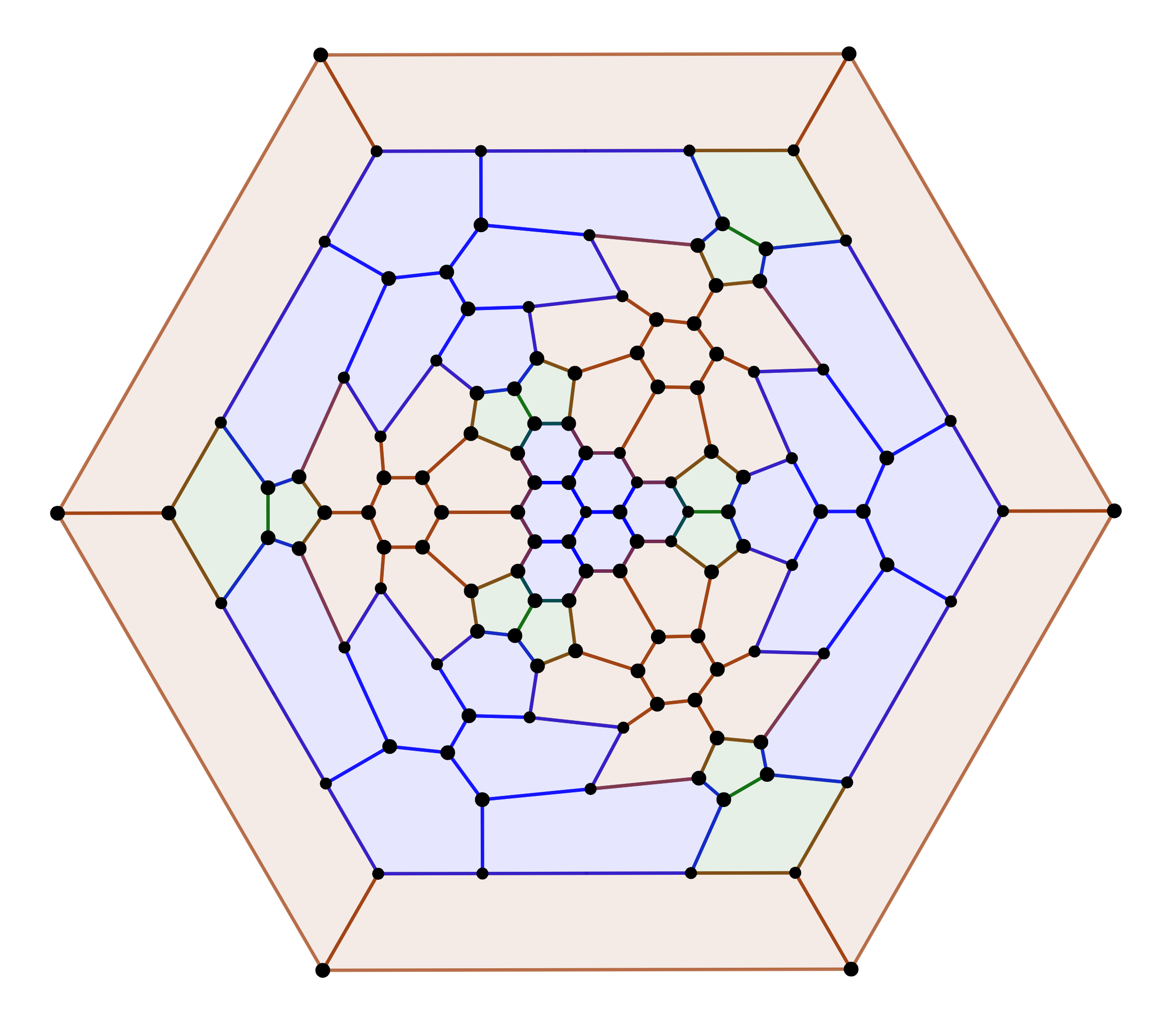

Here, a triangle of 3 red hexagons lives at the center of each face of the original tetrahedron. The pairs of pentagons are colored in green and live at the center of every original edge. The remaining hexagons are colored in blue, and must be symmetric about the original vertices. In this case, they turn out to be arranged in the same figures as the face-centered hexagons.

Like Goldberg polyhedra, we can denote this solution by a path between pentagons. The path between those sharing an edge will always be (1, 0), so this path is unremarkable. There also exists a path from one pentagon of a pair to another of a pair, starting from the edges which border the face of the base tetrahedron. In the TTT, we get to another pentagon after crossing one edge without turning, and in the new solution, we get to another pentagon after crossing two edges without turning. Thus, the former can be parametrized by (1, 0) and the latter by (2, 0).

Let’s extend the figure once more before generalizing. The hexagons in the center of the face are arranged in triangles with two at an edge, bordering a pentagon. Keeping the pentagon in the center of the edge, we can extend the triangle of hexagons so that there are four at an edge:

The left and right diagrams have slightly different colorings – some red hexagons are changed into blue ones so that the blue hexagons form triangles, like in previous figures. This makes it easier to generalize solutions, since the vertex figures steadily increase along triangular numbers. However, the face figures have gone from a triangular arrangement to a hexagonal one. Despite this, the figure does indeed have a (3, 0) path.

For a path (n, 0), there are n + 1 polygons (both hexagons and pentagons) on the edge of a face figure. With the pentagons, these figures make up triangles, so there are \Delta_{n + 1} - 3 hexagons on every face, where \Delta_n is a triangular number. On the vertices, every edge we cross along the path corresponds to a hexagon also on the edge of a triangular vertex figure, giving \Delta_{n} more hexagons. This means that a solution has 4(\Delta_{n + 1} + \Delta_{n} - 3) = 4((n + 1)^2 - 3) hexagons.

Bottom row: vertex figures, same.

| Parameter | F_6 | V | E |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1, 0) | 4 | 28 | 42 |

| (2, 0) | 24 | 68 | 102 |

| (3, 0) | 52 | 124 | 186 |

| (4, 0) | 88 | 196 | 294 |

| (5, 0) | 132 | 284 | 426 |

Whirled Solutions

In the above solutions, we never had to turn to complete our paths. This may leave one wondering whether the parameters are written as 2-tuples to match the other tables, or if we can truly create solutions that incorporate turns.

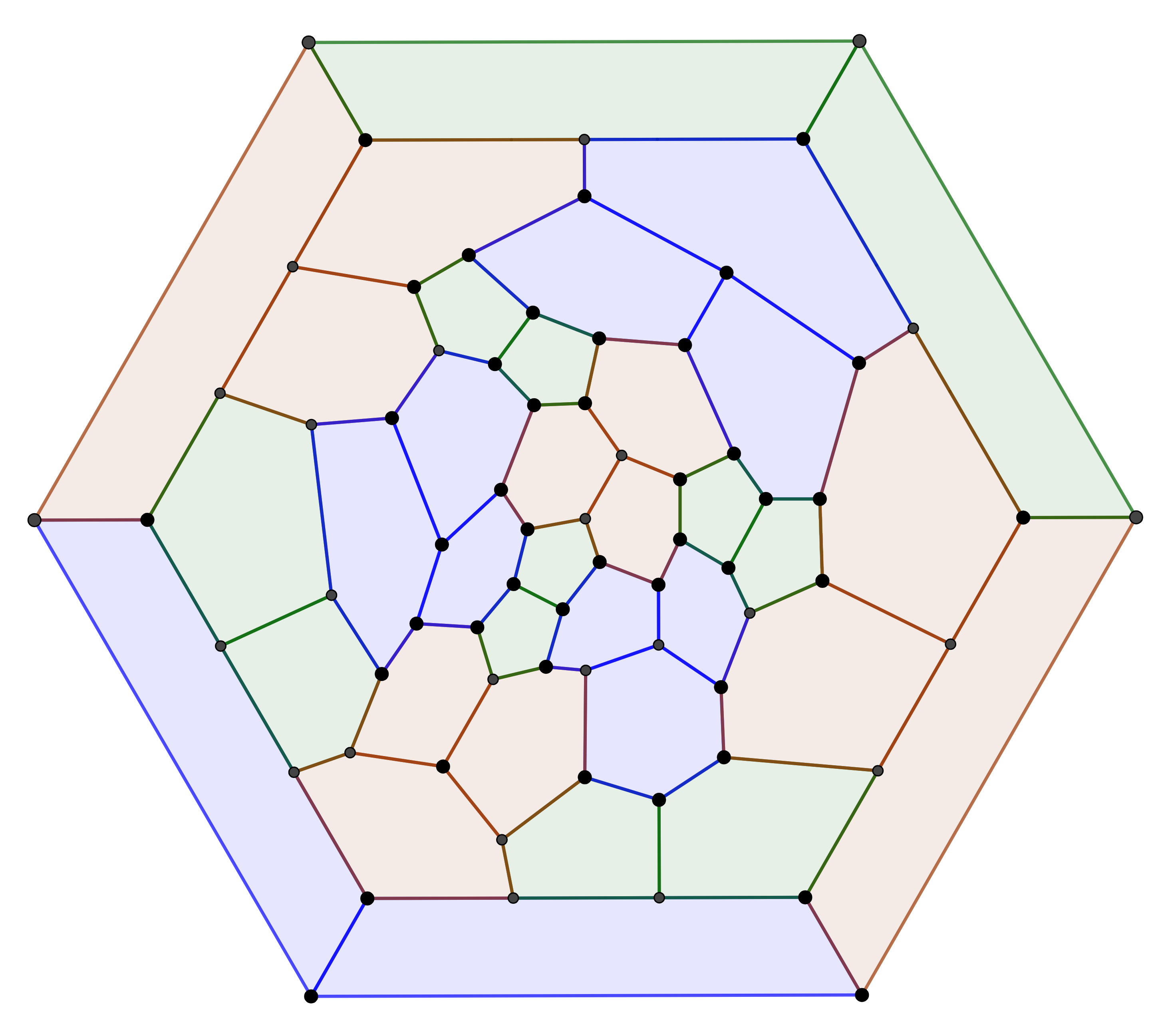

One of the assumptions we made when building face figures was that there was an even triangular number of hexagons, with a pentagon at the center of the edges of the figure. But the pentagons could easily border any of the other hexagons, as long as the figure had triangular symmetry.

As shown on the above diagram, we get a figure on the faces which is similar to Class III Goldberg sectors. This is reinforced by showing the “whirled” (2, 1) path. Just as before (1, 2) path is also possible on this figure, if the path is taken counterclockwise.

We can indeed assemble these figures into a solution:

Similarly to the (3, 0) solution, the face and vertex figures in the recoloring are hexagons and triangles. However, their roles have swapped; this time, the faces are the former and the vertices are the latter. This yields 4(7 + 3) = 40 hexagons in total, which coincides with the tetrahedral antitruncation (3, 3) from earlier.

I suspect that this can be generalized, but I have yet to prove this construction works consistently.

What about Class II?

A parallel to Class II Goldberg solution likely does not exist. For both arms of the path to be equal, the hexagon we turn on must be at the center of a face. The center of the face is equidistant from the midpoints of edges and from the vertices making it up. The former case is the Class I solutions, which have no turn. The latter case is impossible, because the pentagons must be placed along an edge.

Double-Goldberg

Every one of these solution figures, both constructed and otherwise, can be extended using one of the previously-discussed Goldberg-Coxeter Conway operators (dk, tk, c_n = du_nd, and w) to create another solution while preserving tetrahedral symmetry. Some of the easily-constructible solutions based on Goldberg polyhedra are accumulated in the table below.

| (Tetrahedral Goldberg) Parameter | Conway | F_6 | V | E | Paths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c(3, 0) | ct_6kT | 46 | 112 | 168 | \textcolor{red}{(2, 0)}, \textcolor{blue}{(2, 0)} |

| c(2, 2) | ct_6uT | 70 | 160 | 240 | \textcolor{red}{(2, 0)}, \textcolor{blue}{(2, 2)} |

| c(4, 1) | ct_6gtT | 142 | 304 | 456 | \textcolor{red}{(2, 0)}, \textcolor{blue}{w(4, 2)} |

| dk(3, 0) | dkt_6kT | 32 | 84 | 126 | \textcolor{red}{(1, 1)}, \textcolor{blue}{(1, 1)} |

| dk(2, 2) | dkt_6uT | 50 | 120 | 180 | \textcolor{red}{(1, 1)}, \textcolor{blue}{(3, 0)} |

| dk(4, 1) | dkt_6gtT | 104 | 228 | 342 | \textcolor{red}{(1, 1)}, \textcolor{blue}{(4, 1), (3, 3)} |

| tk(3, 0) | tkt_6kT | 116 | 252 | 378 | \textcolor{red}{(3, 0)}, \textcolor{blue}{(3, 0)} |

| tk(2, 2) | tkt_6uT | 170 | 360 | 540 | \textcolor{red}{(3, 0)}, \textcolor{blue}{(3, 3)} |

| tk(4, 1) | tkt_6gtT | 332 | 684 | 1026 | \textcolor{red}{(3, 0)}, \textcolor{blue}{w(6, 3)} |

| w(3, 0) | wt_6kT | 88 | 196 | 294 | \textcolor{red}{(2, 1)}, \textcolor{blue}{(2, 1)} |

| w(2, 2) | wt_6uT | 130 | 280 | 420 | \textcolor{red}{(2, 1)}, \textcolor{blue}{(4, 1)} |

| w(4, 1) | wt_6gtT | 256 | 532 | 798 | \textcolor{red}{(2, 1)}, \textcolor{blue}{(5, 3), (6, 3)} |

The same operators can also be applied to the edge-based cases, but since I have not computationally generated these, I will not attempt to tabulate them. Doing so would require that I:

Formalize the construction of the graph, preferably by writing a program which can identify identical vertices.

- I did this step manually to sketch the figures

Find good planar and spherical embeddings of the graph.

(Optionally,) import and display the result in a polyhedron viewer, preferably one which can apply Conway notation to an arbitrary figure

Closing

Tetrahedral solutions are vastly more complicated since we not restricted to corresponding pentagons with faces on a dodecahedron, In decreasing the amount of symmetry, the amount of free parameters increases. Pentagons are no longer regular, any(?) arrangement with thrice-rotational symmetry per face is valid, and I am unsure whether the resultant polyhedra can even be made equilateral.

Despite claiming existence of these tetrahedral solutions topologically, actual geometric construction of some is difficult. In fact, I made an error while constructing one of the edge-based solutions:

The face in the center has been replaced with its chiral opposite. You can check this by trying to consistently follow the path (2, 1) – along the center face, you need to follow (1, 2) instead.

As you may be able to guess, not even specifying tetrahedral symmetry is enough to completely classify every solution. The next post will discuss additional solutions, some of whose members cannot be constructed using common seed polyhedra.

Polyhedron images were generated using polyHédronisme. Nets and graphs were created with GeoGebra.

Footnotes

- ↩︎

The equation we used to obtain the “12 pentagons” figure also applies to the tetrahedron, with some adjustments:

\begin{align*} \chi &= V - E + F_3 + F_n \\ 2n\chi &= 2nV - \textcolor{red}{2nE} + 2nF_3 + 2nF_n + \textcolor{blue}{0}\\ &= 2nV - \textcolor{red}{\stackrel{3V = 2E}{3nV}} + 2nF_3 + 2nF_n + \textcolor{blue}{\stackrel{3V = 3F_3 + nF_n}{ 6V - 6F_3 - 2nF_n }} \\ &= (6 - n)V + (2n - 6)F_3 \\ &= 4n \end{align*}

From this, it is discerned that there are 4 vertices (n = 3) or 4 trianglar faces (n = 6), with the rest of the faces being hexagons.

- ↩︎

Consider the equation a^2 + ab + b^2 = 2. Since 0 and 1 are the only squares mod 3, we can build a table out of each possibility:

a^2 b^2 a^2 + ab + b^2 = 2 Possible? 0 0 ab \equiv 2, but a and b must be multiples of 3 No 0 1 ab \equiv 1, but a is a multiple of 3 No 1 0 Same as in the above case, but for b No 1 1 ab \equiv 0, but neither of a or b is a multiple of 3 No On the other hand, if b \equiv 0, then the norm is a^2, which is either 0 or 1.