A Game of Permutations, Appendix

Partial Cayley graphs of Coxeter diagrams

This post is an appendix to another post discussing the basics of Coxeter diagrams. It focuses on transforming path-like swap diagrams into proper A_n Coxeter diagrams, which correspond to symmetric groups. This post focuses on the graphs made by the cosets made by removing a single generator (i.e., a vertex of the Coxeter diagram).

For finite diagrams whose order is not prohibitively big, I will also provide an embedding as a permutation group by labelling each generator in the Coxeter diagram. Since each generator is the product of disjoint swaps, I will also show their swap diagrams, as well as interactions via the edges.

Platonic Symmetry

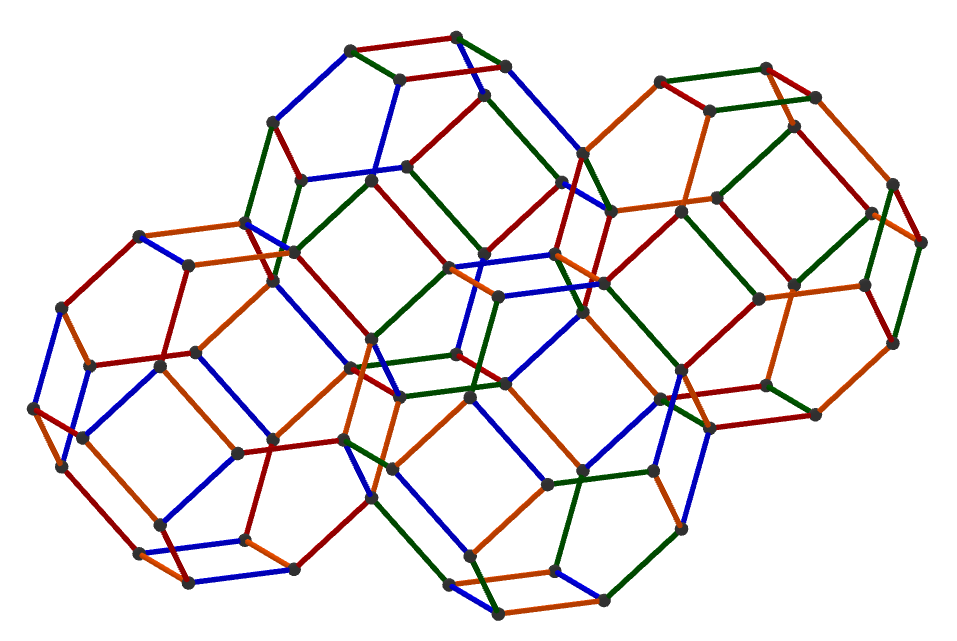

The symmetric group S_n also happens to describe the symmetries of an (n-1)-dimensional simplex. The 3-simplex is simply a tetrahedron and has symmetry group T_h, which is isomorphic to S_4. We know that S_4 can be encoded by the diagram A_3.

The string {3, 3} can be read across the edges of A_3, denoting the order of certain symmetries. This happens to coincide with another datum of the tetrahedron: its Schläfli symbol. It describes triangles (the first 3) which meet in triples (the second 3) at a vertex. It may also be interpreted as the symmetry of the 2-dimensional components (faces) and the vertex-centered symmetry. The Wikipedia article on the tetrahedron presents both of these objects in its information column.

The image above shows more sophisticated diagrams alongside A_3, which I will not attempt describing (mostly because I don’t completely understand them myself). Other Platonic solids and their higher-dimensional analogues have different Schläfli symbols, and correspond to different Coxeter diagrams.

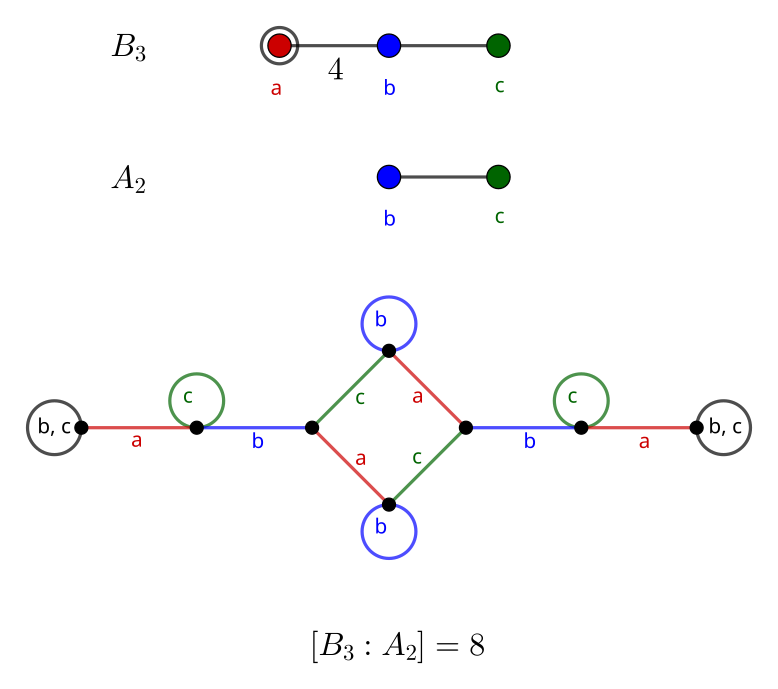

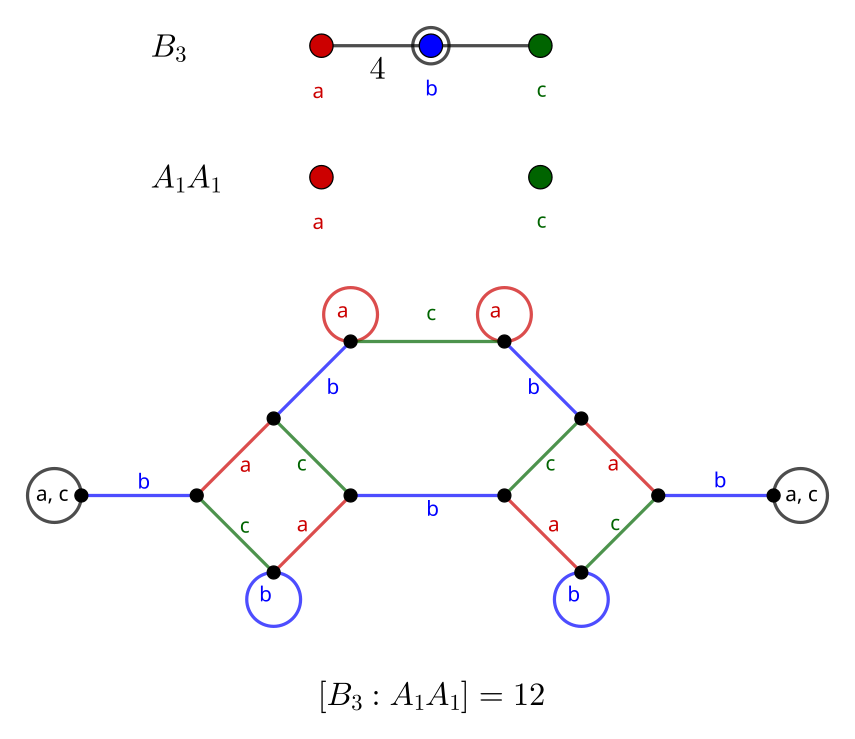

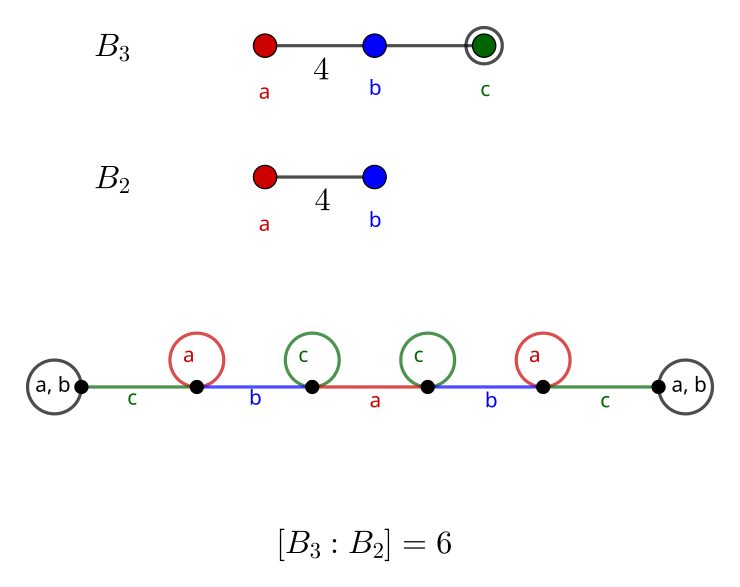

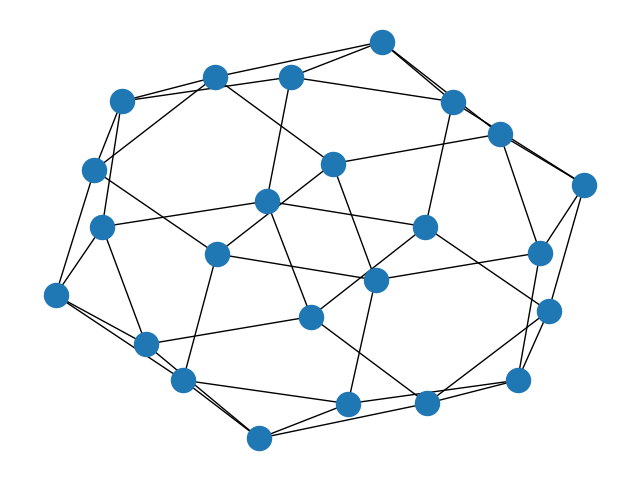

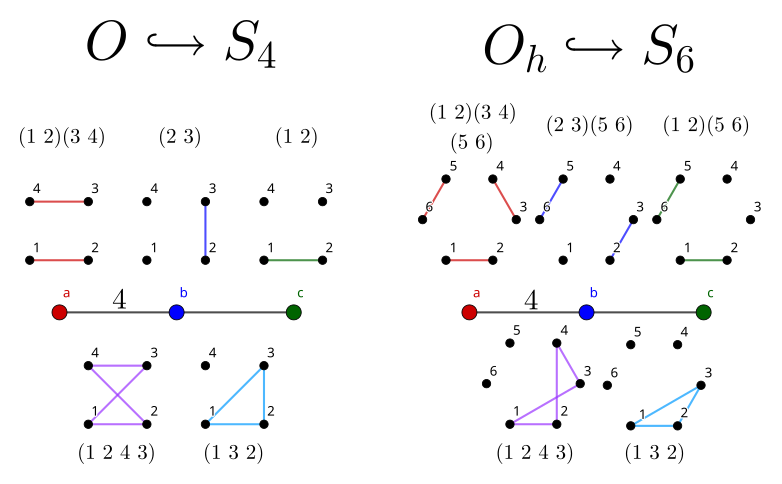

B_3: Octahedral Group

Adding an order-4 product into the mix makes things a lot more interesting. The cube (Schläfli symbol {4, 3}) and octahedron ({3, 4}) share a symmetry group, O_h, which corresponds to the B_3 diagram1.

The center graph is the first to have a hexagon created by removing a single generator. Meanwhile, the third graph is entirely path-like, similar to the ones created by removing an endpoint from the A_n diagrams. In the same vein, the graph for B_3 resembles the graph for A_3 made by removing the center generator, albeit with two extra vertices.

Going across left to right, the order suggested by each index is:

- 8 \cdot |A_2| = 8 \cdot 6 = 48

- 12 \cdot |A_1 A_1| = 12 \cdot 4 = 48

- 6 \cdot |B_2| = 6 \cdot 8 = 48

- B_2 describes the symmetry of a square (i.e., \text{Dih}_4, the dihedral group of order 8)

Each diagram suggests the same order, which is good. A simple embedding which obeys the edge condition assigns (1 ~ 2)(3 ~ 4) to a, (2 ~ 3) to b, and (1 ~ 2) to c. Then ab = (1 ~ 2 ~ 4 ~ 3) has order 4, bc = (1 ~ 3 ~ 2) has order 3, and ac obviously has order 2.

There’s a problem though. These are all elements of S_4, and in fact, generate it (in fact, S_4 \cong O, the rotational symmetries of a cube). The group we want is O_h \cong S_4 \times \mathbb{Z}_2. If we want to embed a group of order 48 in a symmetric group, we need one for which 48 divides its order. 48 divides |S_6| = 720, and indeed, a quick fix is just to multiply each generator by another disjoint 2-cycle like (5 ~ 6).

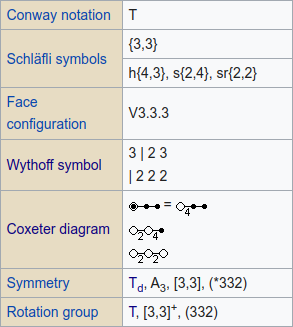

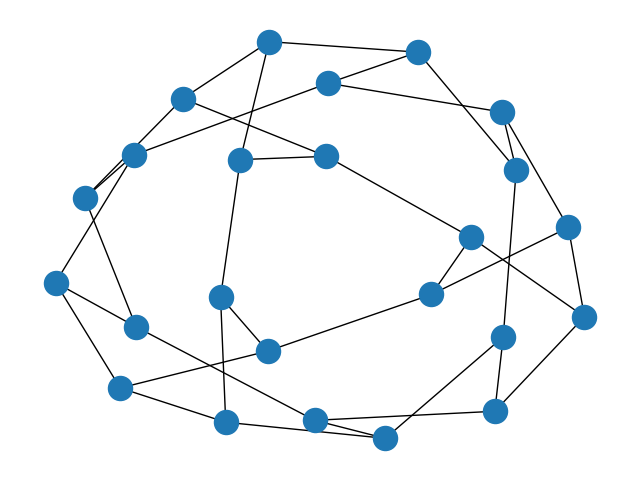

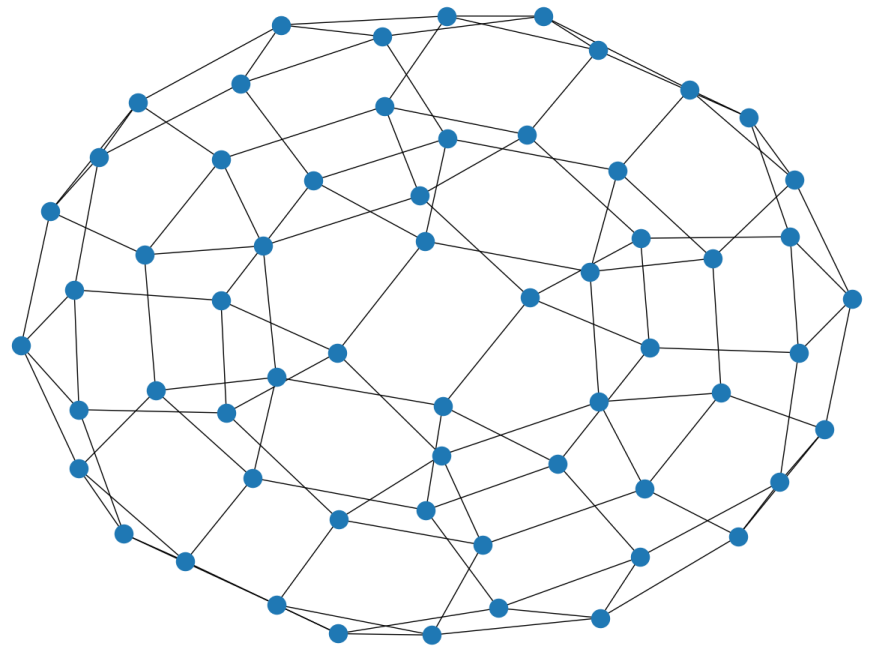

These two embeddings generate different (proper) Cayley graphs. The one for O has 24 vertices and is nonplanar. On the other hand, the one for O_h is planar, and is the skeleton of the truncated cuboctahedron, a figure composed of octagons, hexagons, and squares. These shapes are exactly what those implied by the orders of the products in the Coxeter diagram. Note also that the cuboctahedron is the figure produced halfway between dualizing the cube and octahedron by shrinking faces (their rectification).

In either case, the products of adjacent generators (the permutations on the edges) are the same. When made into a Cayley graph, these products generate the rhombicuboctahedron, which is another shape that is in some sense midway between the cube and octahedron. Since all of these generators are in S_4, it only has half the number of vertices as the truncated cuboctahedron.

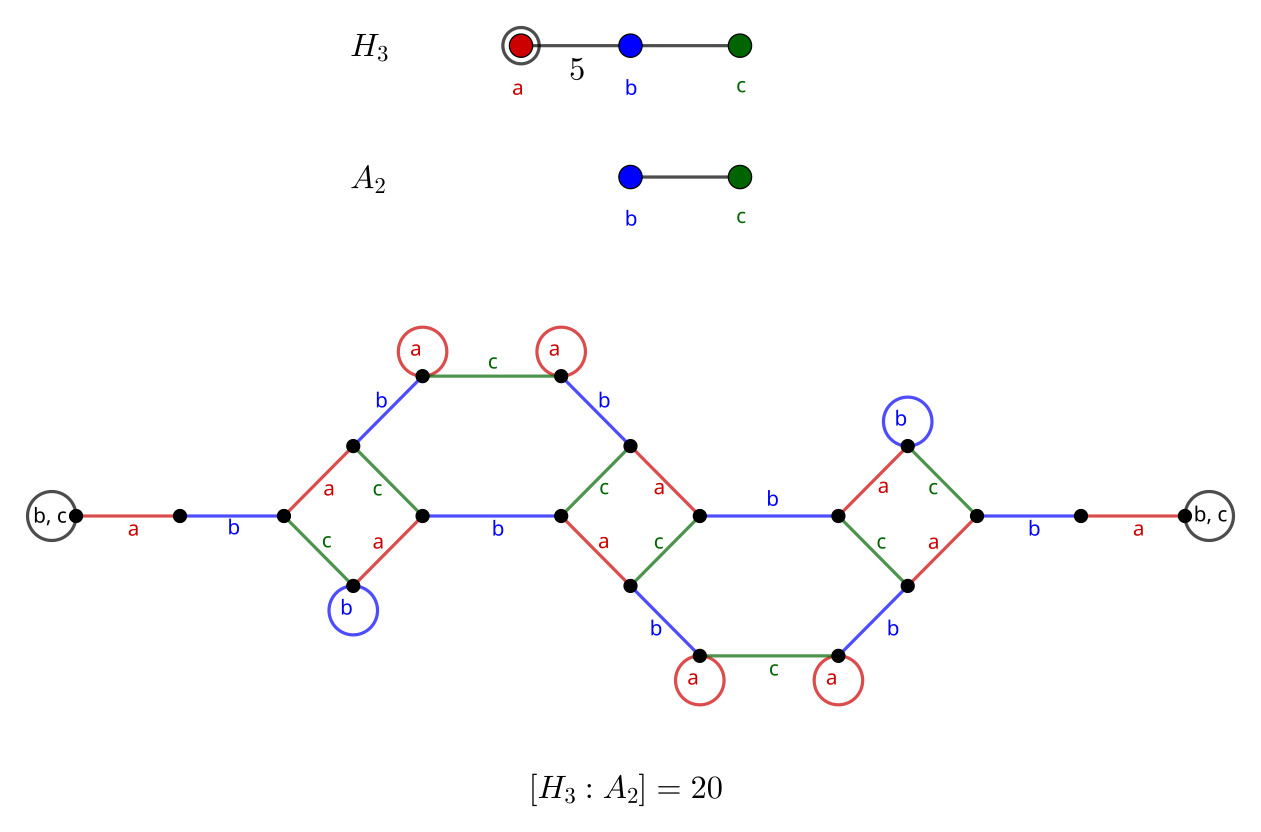

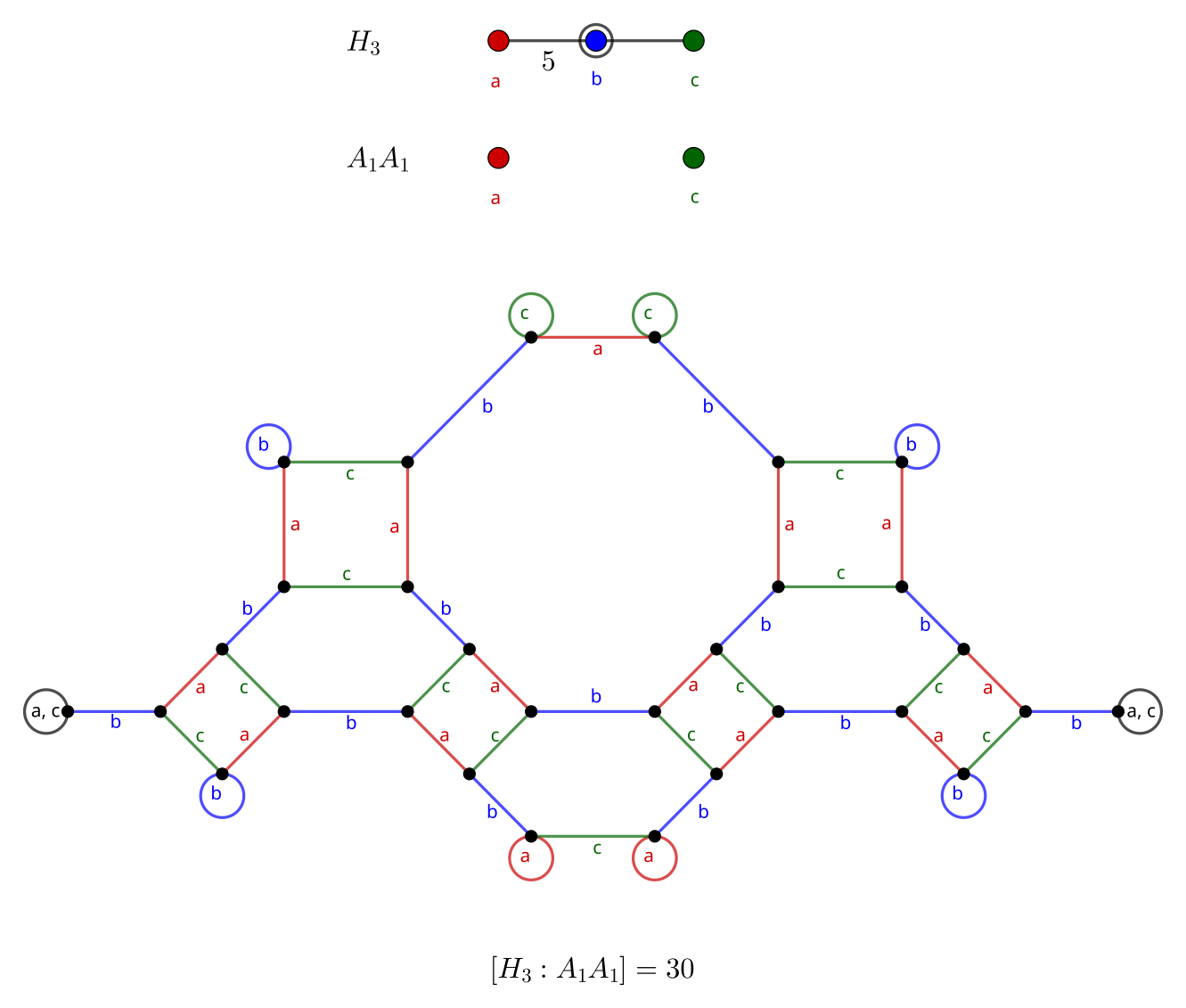

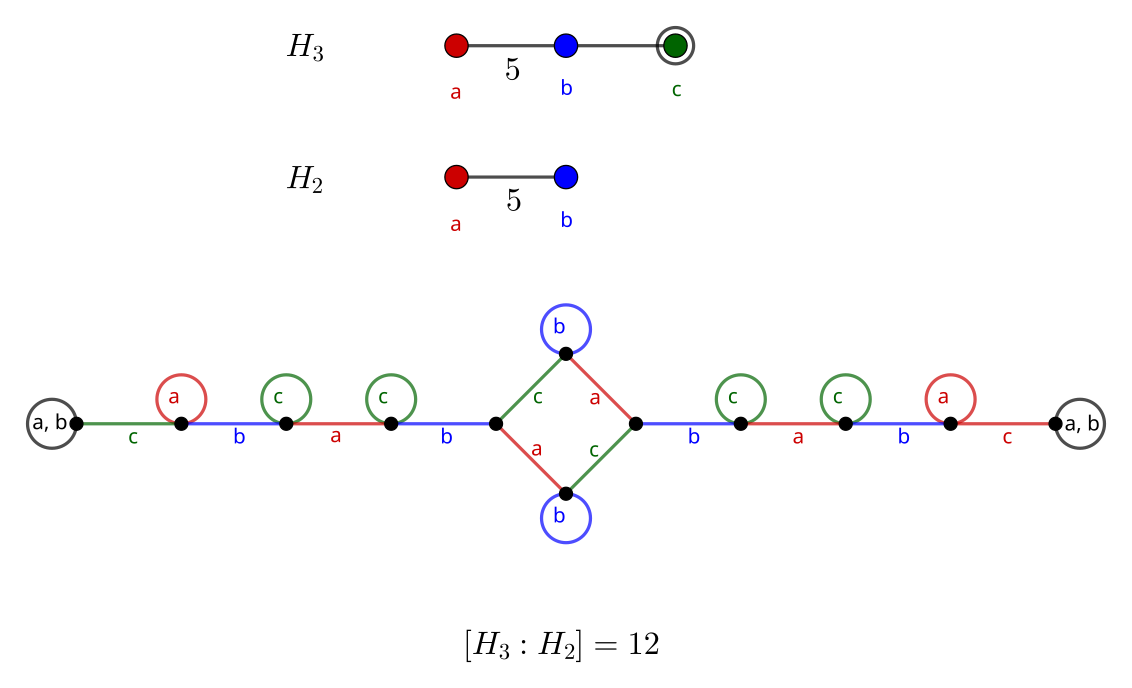

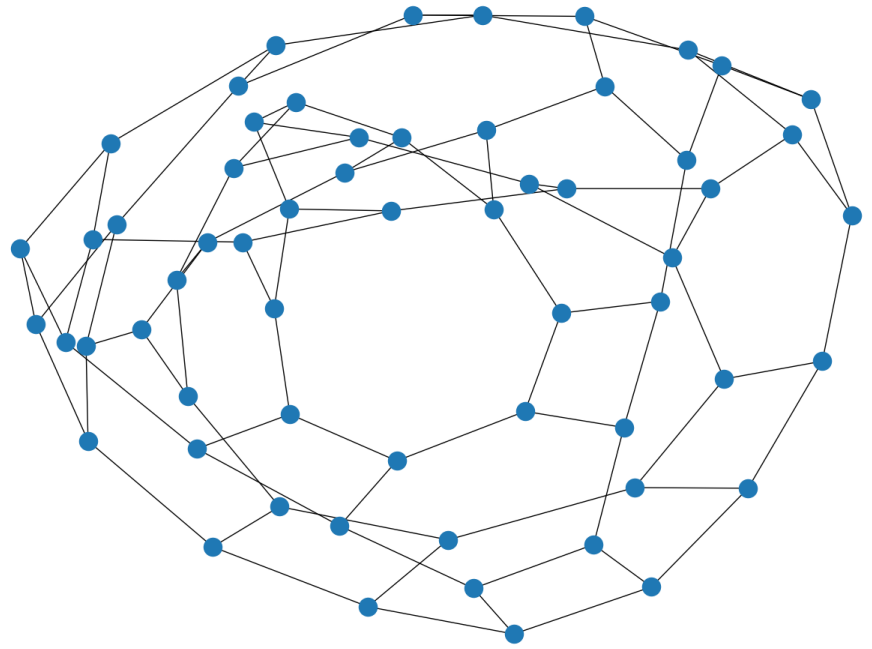

H_3: Icosahedral Group

Continuing with groups based on 3D shapes, the dodecahedron (Schläfli symbol {5, 3}) and icosahedron ({3, 5}) also share a symmetry group. It is known as I_h and corresponds to Coxeter diagram H_3.

Two of these graphs are similar to the cube/octahedron graphs. The middle contains a decagon, corresponding to the order 5 product between a and b.

We have the orders:

- 20 \cdot |A_2| = 20 \cdot 6 = 120

- Graph resembles an extension of the graph of B_3 / A_1 A_1, as hexagons joining blocks of squares

- 30 \cdot |A_1 A_1| = 30 \cdot 4 = 120

- 12 \cdot |H_2| = 12 \cdot 10 = 120

- Graph resembles an extension of the graph of B_3 / A_2, as a single square joining paths

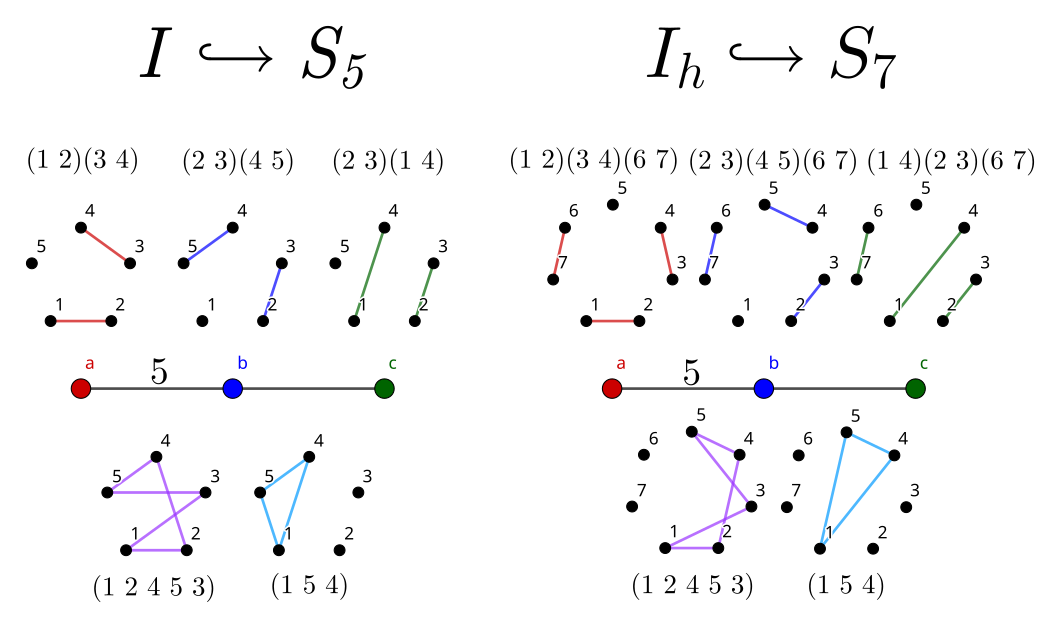

The order 120 is the same as the order of S_5, which corresponds to diagram A_4. However, these are not the same group, since I_h \cong \text{Alt}_5 \times \mathbb{Z}_2 \ncong S_5. A naive (though slightly less obvious) embedding, found similarly to B_3’s, incorrectly assigns the following:

- a = (1 ~ 2)(3 ~ 4)

- b = (2 ~ 3)(4 ~ 5)

- c = (2 ~ 3)(1 ~ 4)

This is certainly wrong, since all these permutations are within S_5. Actually, they are all even permutations and in fact generate I \cong \text{Alt}_5, with order 60. Yet again, multiplying a disjoint 2-cycle (in this case, (6 ~ 7)) to each generator boosts the order to 120 and gives a proper embedding of I_h.

Similarly to B_3, the first, incorrect embedding gives a nonplanar Cayley graph. The second one gives a planar graph, the skeleton of the truncated icosidodecahedron. It consists of decagons, hexagons, and squares, just like those which appear in the graphs above. The icosidodecahedron is also the rectification of the dodecahedron and icosahedron. In this case, the edges generate the rhombicosidodecahedronal graph.

It is remarkable that the truncations of the rectifications2 have skeleta that are the same as the Cayley graphs generated by their respective Platonic solids’ Coxeter diagrams. In a way, these figures describe their own symmetry. Also, both of these figures belong to a class of polyhedra known as zonohedra.

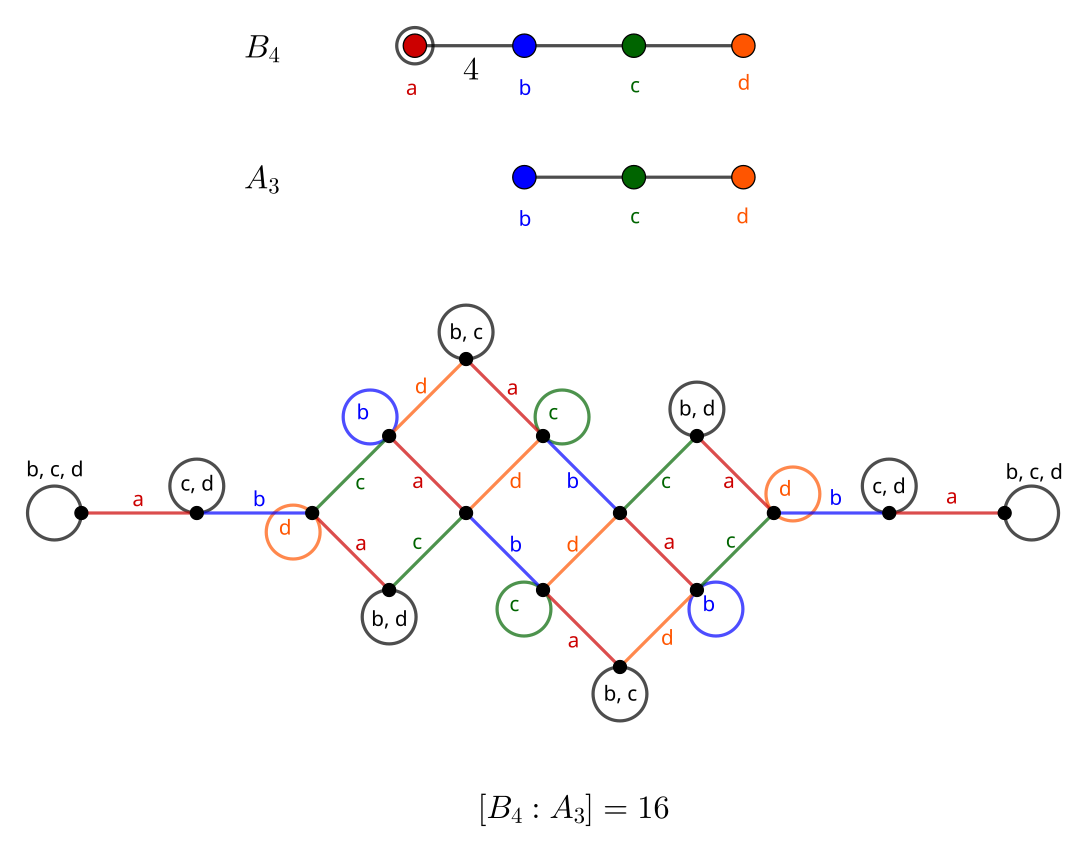

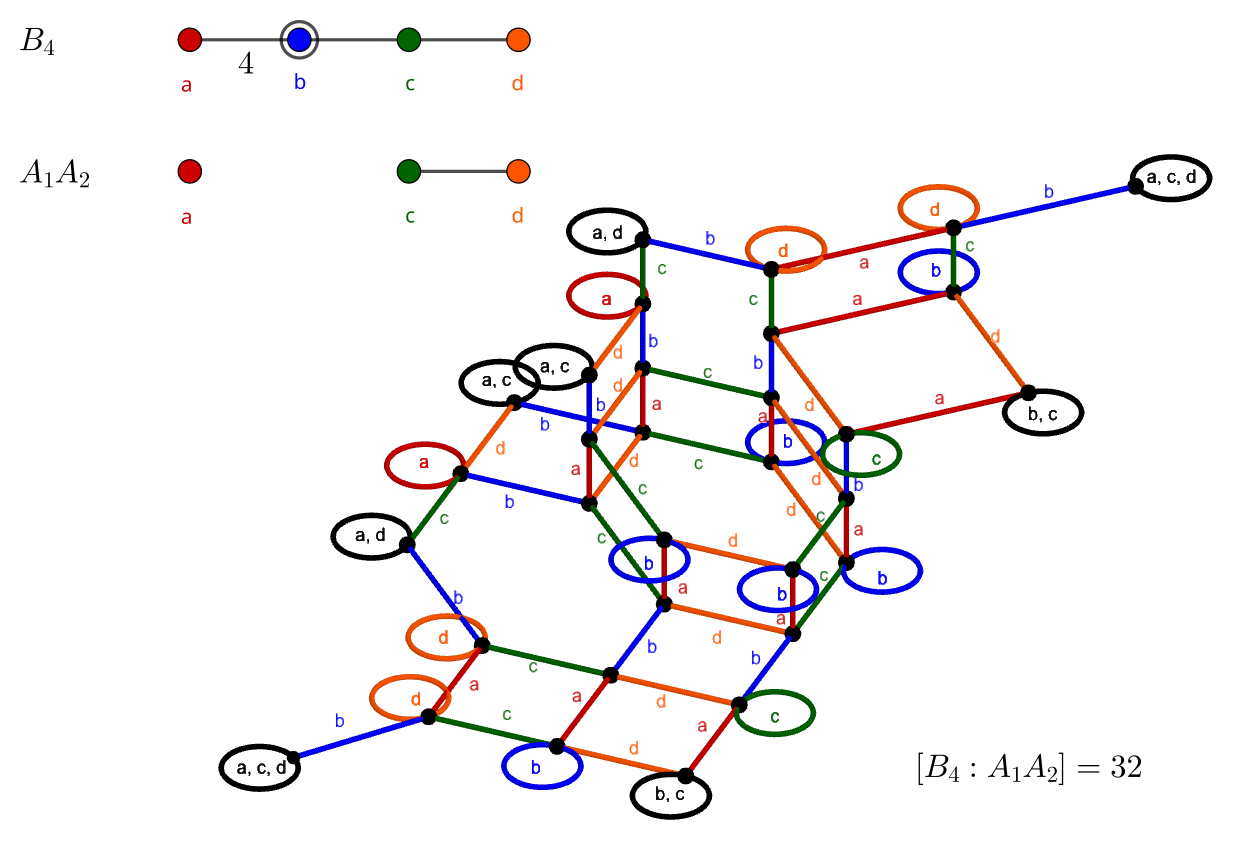

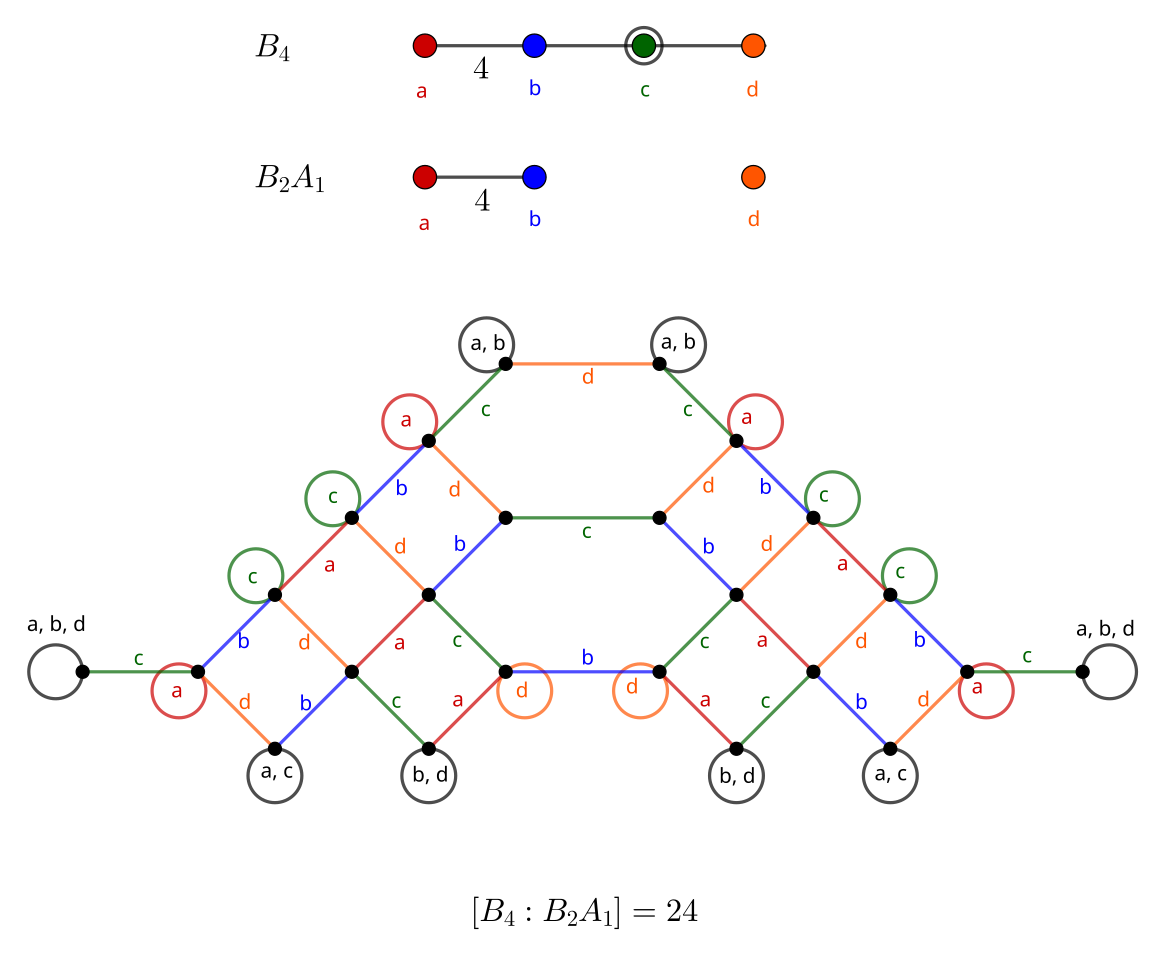

B_4: Hyperoctahedral Group

Up a dimension from the cube and octahedron lie their 4D counterparts: the tesseract (Schläfli symbol {4, 3, 3}, interpreted as three cubes ({4, 3}) around an edge) and 16-cell ({3, 3, 4}, four tetrahedra ({3, 3}) around an edge). They correspond to Coxeter diagram B_4.

Three of these graphs (those starting with a, c, and d) are also similar to those encountered one dimension lower. The remaining graph is best understood in three dimensions, befitting the 4D symmetries it encodes. It appears to have similar regions to the omnitruncated tesseract, featuring both the truncated octahedron and hexagonal prism cells.

We have the orders:

- 16 \cdot |A_3| = 16 \cdot 24 = 384

- Graph resembles an extension of B_3 / A_2, as squares connecting paths

- 32 \cdot |A_1 A_2| = 32 \cdot 2 \cdot 6 = 384

- 24 \cdot |B_2 A_1| = 24 \cdot 8 \cdot 2 = 384

- Graph resembles an extension of B_3 / A_1 A_1, as hexagons joining blocks of squares

- 8 \cdot |B_3| = 8 \cdot 48 = 384

- Graph resembles an extension of A_3 / A_2, a simple path

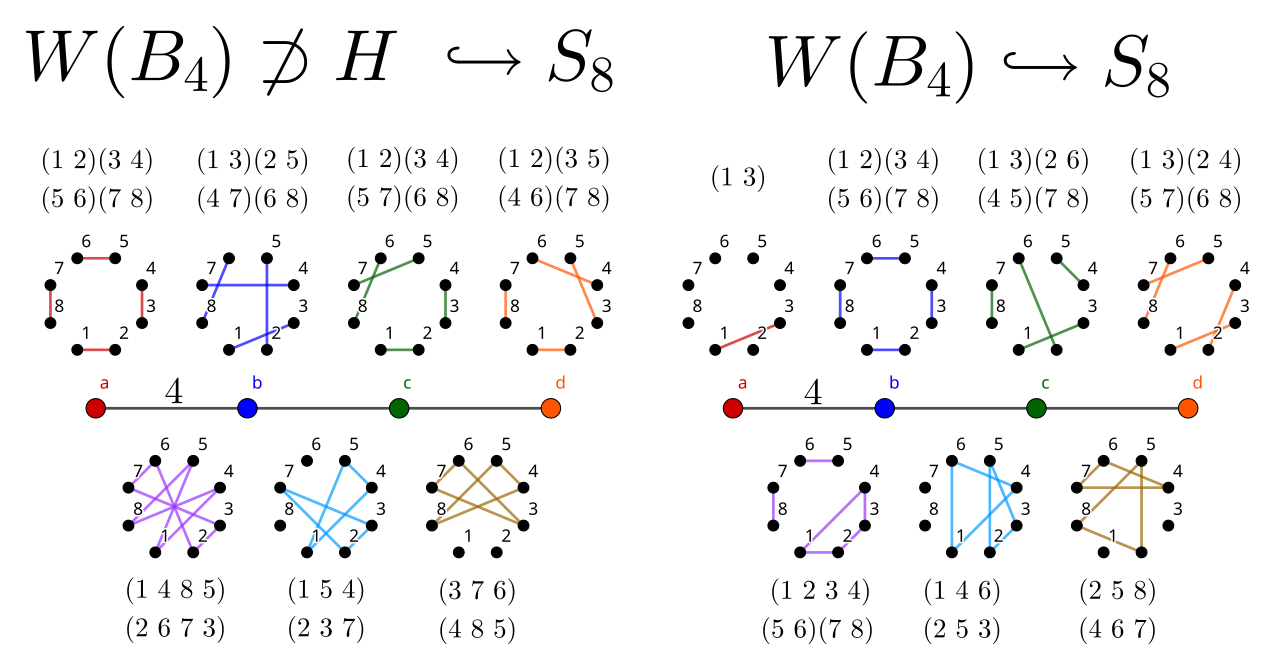

The order of the group, 384, suggests that it needs to be embedded in at least S_8 since 384 ~ \vert ~ 8! ~ ( = 40320). Indeed, such an embedding exists (found by computer search rather than by hand):

- a = (1 ~ 3)

- b = (1 ~ 2)(3 ~ 4)(5 ~ 6)(7 ~ 8)

- c = (1 ~ 3)(2 ~ 6)(4 ~ 5)(7 ~ 8)

- d = (1 ~ 3)(2 ~ 4)(5 ~ 7)(6 ~ 8)

Notably, this embedding takes advantage of an order 4 product between an order 2 and an order 4 element.

A similar computer search yielded an insufficient embedding in S_8, with order 192:

- a = (1 ~ 2)(3 ~ 4)(5 ~ 6)(7 ~ 8)

- b = (1 ~ 3)(2 ~ 5)(4 ~ 7)(6 ~ 8)

- c = (1 ~ 2)(3 ~ 4)(5 ~ 7)(6 ~ 8)

- d = (1 ~ 2)(3 ~ 5)(4 ~ 6)(7 ~ 8)

This false embedding cannot be “fixed” by multiplying some generators3 by (9 ~ 10) (implicitly embedding in S_{10} instead). Quickly “running” the generators shows that the order of the group is unchanged by this maneuver. Much of the structure permutations ensures that nonadjacent vertices still have order-2 products.

I won’t try to identify either of these generating sets’ Cayley graphs since it is impractical to try comparing graphs of this size (and they likely correspond to a 4D object’s skeleton). In fact, H appears to not be isomorphic to a subgroup of W(B_4). The latter has at least 2 subgroups of order 192: one generated by the edges in the above embedding, and one containing only the even permutations. These are distinct from one another, since the number of elements of a particular order is different. The latter subgroup is closer to H, matching the number of elements of each order, but the even permutations have commutator subgroup of order 96 while H has a commutator subgroup of order 48.

Other Finite Diagrams

Higher-dimensional Platonic solids are hardly the limits of what these diagrams can encode. The following three diagrams also give rise to finite graphs.

D_4

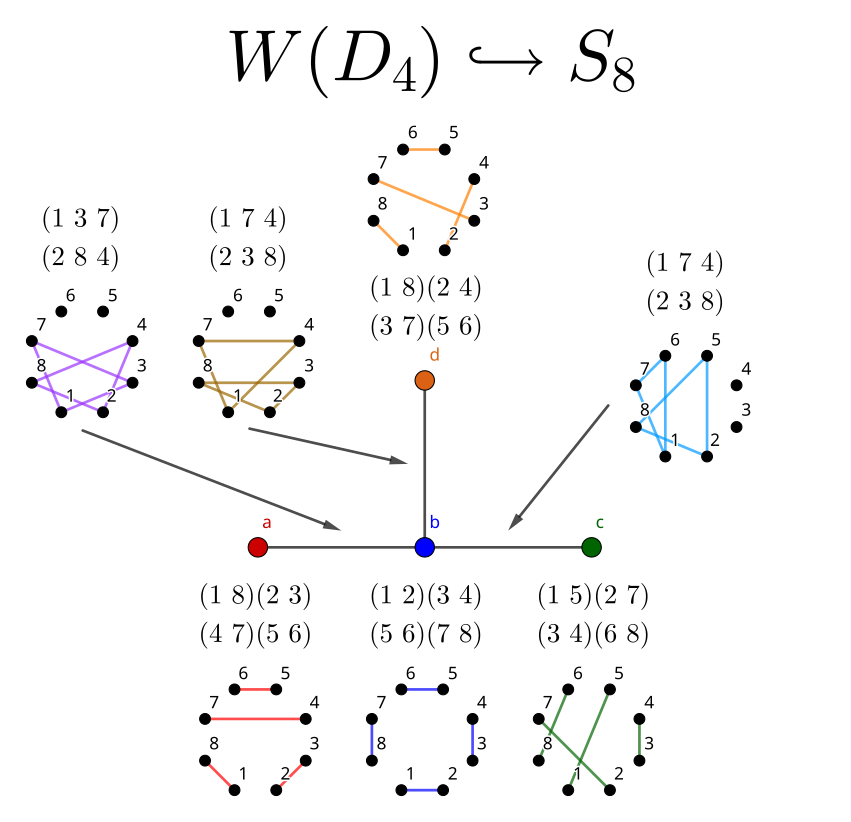

D_4 is the first Coxeter diagram with a branch. Like B_4 before it, it is corresponds to the symmetries of a 4D object. We only really have two choices in which generator to remove, which generate the following graphs:

While we could also remove c or d, this would just produce a graph identical to the one on the left, just with different labelling. The right diagram is rather interesting, as it can be described geometrically as two cubes attached to three hexagons sharing an edge.

Both of these cases give the order

- 8 \cdot |A_3| = 8 \cdot 24 = 192

- 24 \cdot |A_1 A_1 A_1| = 24 \cdot 8 = 192

The minimum degree of symmetric group is S_8, since 192 ~ \vert ~ 40320. Fortunately, a computer search yields a correct embedding immediately:

- a = (1 ~ 8)(2 ~ 3)(4 ~ 7)(5 ~ 6)

- b = (1 ~ 2)(3 ~ 4)(5 ~ 6)(7 ~ 8)

- c = (1 ~ 5)(2 ~ 7)(3 ~ 4)(6 ~ 8)

- d = (1 ~ 8)(2 ~ 4)(3 ~ 7)(5 ~ 6)

In fact, the group generated by this diagram is isomorphic to the even permutation subgroup of W(B_4). This can be verified by selecting order 2 elements from the latter which obey the laws in D_4. On the other hand, H and the edge-generated subgroup do not satisfy this diagram.

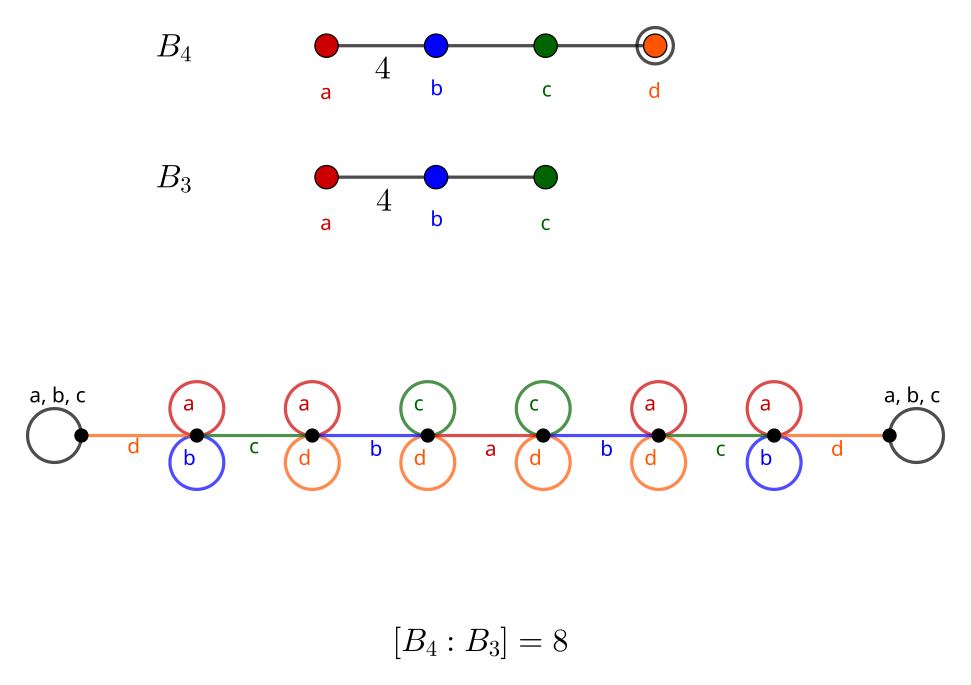

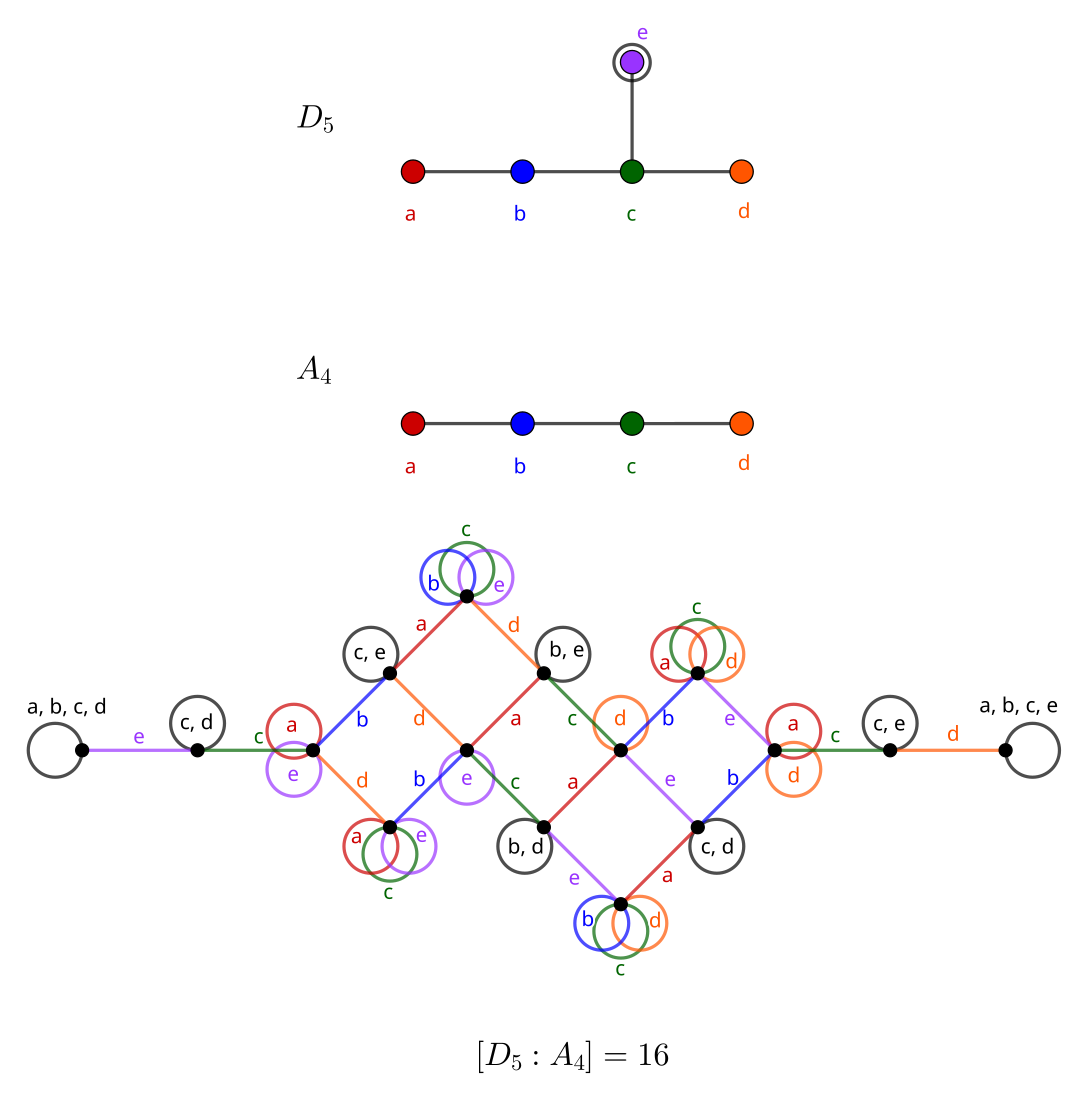

D_5

D-type diagrams continue by elongating one of the paths. The next diagram, D_5, has really only four distinct graphs, of which I will show only two:

First, note how the graph to the right is generated by removing the generator e, but the left and right sides of the diagram are asymmetrical. This is because d and e are equivalent with respect to the branch, and shows us that removing either generator d or e results in the same graph.

The order suggested by each is

- 10 \cdot |D_4| = 10 \cdot 192 = 1920

- 16 \cdot |A_4| = 16 \cdot 120 = 1920

If we were to remove generator b, we’d end up with the diagram A_1 A_3, which generates a group of order 48. The graph would have 1920 / 48 = 40 vertices, which would be fairly difficult to render. Removing generator c would be even worse, since the resulting diagram, A_2 A_1 A_1, has order 24, and the graph would require 80 vertices – twice as many.

Finding an embedding at this point is difficult. The order 1920 also divides 40320 = |S_8|, but computer search has failed to find an embedding in up to S_{11}.

E_6

If one of the shorter paths of D_5 is extended, then we end up with the diagram E_6. I will only show one of its graphs.

Similarly to one of the graphs for D_5, this graph goes in with a and comes out with e, which are again symmetric with respect to the branch. I particularly like how on this graph, most of the squares are structured so that they can bridge to the ae commuting square (middle, bottom).

The order of this group is 27 \cdot 1920 = 51840, which borders on the incomprehensible (if that threshold hasn’t been crossed already). The graphs not shown would have the following number of vertices (which is precisely why I won’t draw them out):

- Removing f: [E_6 : A_5] = 51840 / 720 = 72 vertices

- Removing b or d: [E_6 : A_1 A_4] = 51840 / 240 = 216 vertices

- Removing c: [E_6 : A_2 A_2 A_1] = 51840 / 72 = 720 vertices

Going by order alone, E_6 should embed in S_9 (51840 ~ \vert ~ 9!), but since S_{11} was too small for its subgroup D_5, this too optimistic. I don’t know what the minimum degree is required to embed E_6, but finding it directly it is beyond my computational power.

The E diagrams continue with E_7 and E_8. Each of the three corresponds to the symmetries of semi-regular higher-dimensional objects, whose significance and structure are difficult to comprehend. Their size alone makes continuing onward by hand a fool’s errand, and I won’t be attempting to draw them out right just now.

Infinite (Affine) Diagrams

Not every Coxeter diagram produces a finite, closed graph. Instead, they may proliferate vertices forever. They are termed either “affine” or “hyperbolic”, depending respectively on whether the diagrams join up with themselves or seem to require more and more room as the algorithm advances. This is also related to the collection of fundamental domains and roots that the diagram describes.

Since hyperbolic graphs are difficult to draw, I’ll be restricting myself to the affine diagrams. Unlike hyperbolic diagrams, which are unnamed, affine ones are typically named by altering finite diagrams.

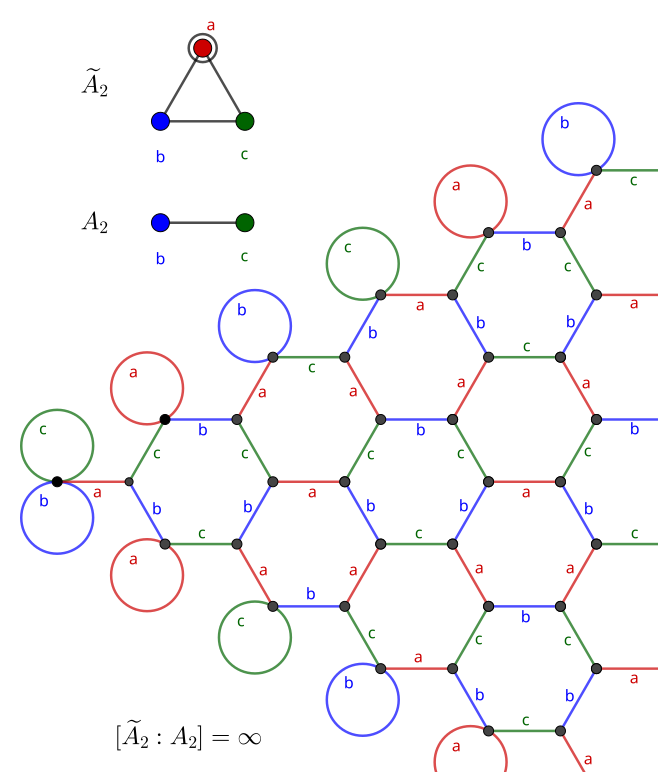

\widetilde A_2

The Coxeter diagram associated to the triangle graph K_3 is called \widetilde A_2. This graph is also the line graph of \bigstar_3 so it might make sense to assign to the vertices the generators (1 ~ 2), (2 ~ 3), and (1 ~ 3), which we know to generate S_3. However, S_3 already has a diagram, A_2, which is clearly a subdiagram of \widetilde A_2, so the new group must be larger.

Attempting to make a graph by following the generators results in an infinite hexagonal tiling. You might recall that A_2 generates a hexagon, so it is intriguing that this generates a tiling based on this shape. There are three distinct types of hexagon – ab, ac, and bc – since each pair of elements has a product of order 3. Removing a pair of vertices from the diagram would get rid of the initial edge (a in this case), and the “limiting case” where all three vertices are removed is just the true hexagonal tiling.

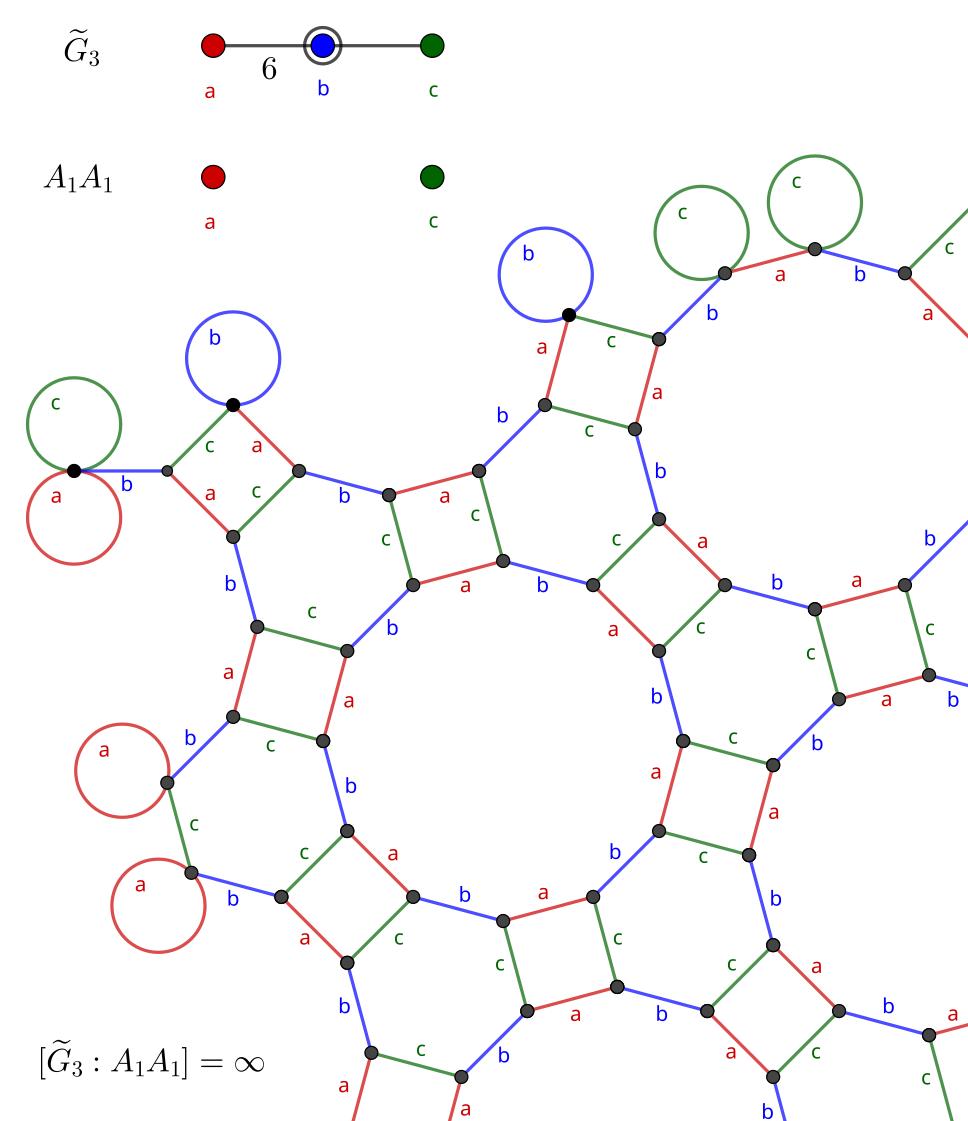

\widetilde G_2

The hexagonal tiling has Schläfli symbol {6, 3}, and is dual to the triangular tiling. As a Coxeter diagram, this symbol matches the Coxeter diagram \widetilde G_2.

The graph generated by removing a generator is another infinite tiling, in this case the truncated trihexagonal tiling. Once again, this tiling is the truncation of the rectification of the symmetry it typically describes. Each pair of prodcuts corresponds to a distinct polygon in the graph: ab to dodecagons, ac to squares, and bc to hexagons.

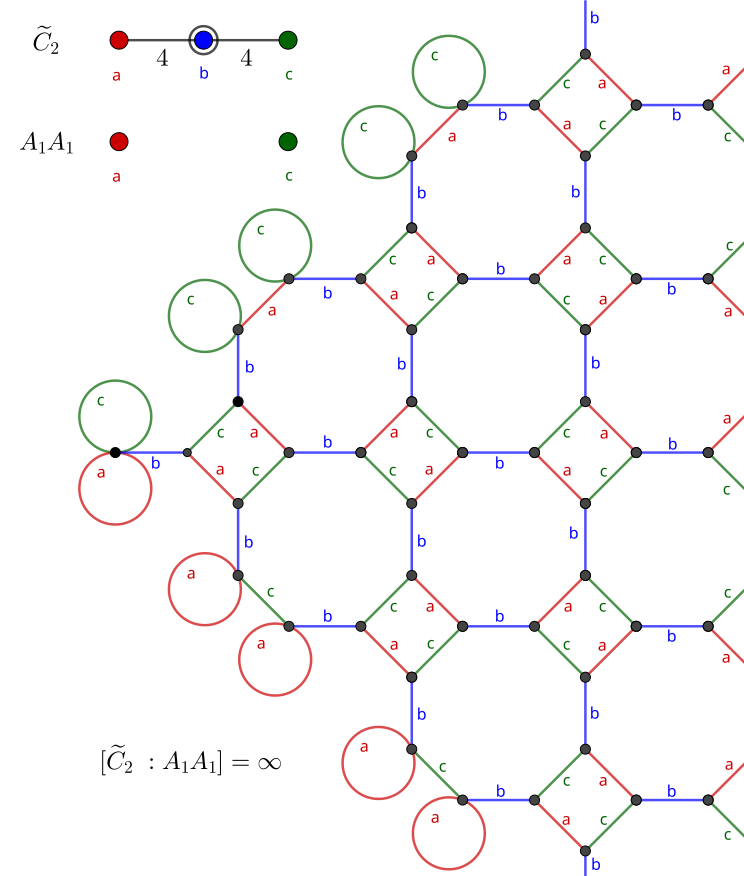

\widetilde C_2

The only remaining regular 2D tiling is the square tiling (Schläfli symbol {4, 4}), whose Coxeter diagram is named \widetilde C_2.

The tiling generated by this diagram is known as the truncated square tiling. Mirroring the other cases, it is also the truncated rectified square tiling, since rectifying the square tiling merely produces another square tiling (rotated 45°). In this tiling, the squares always correspond to the product ac, but there are octagons for both order-4 products, ab or bc.

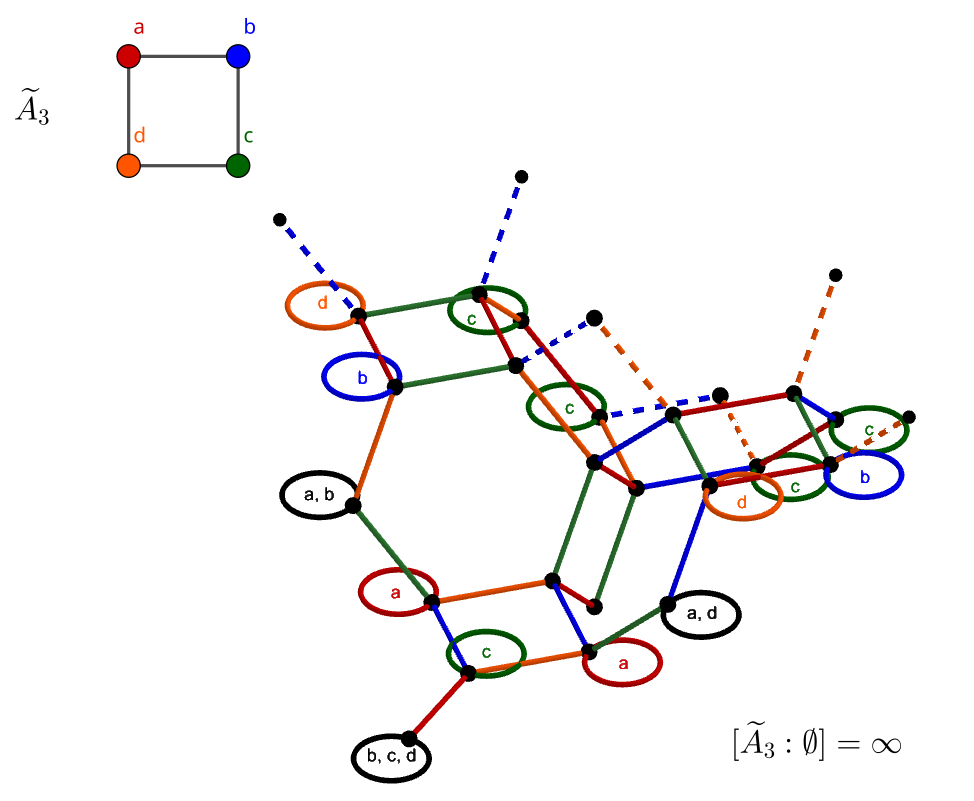

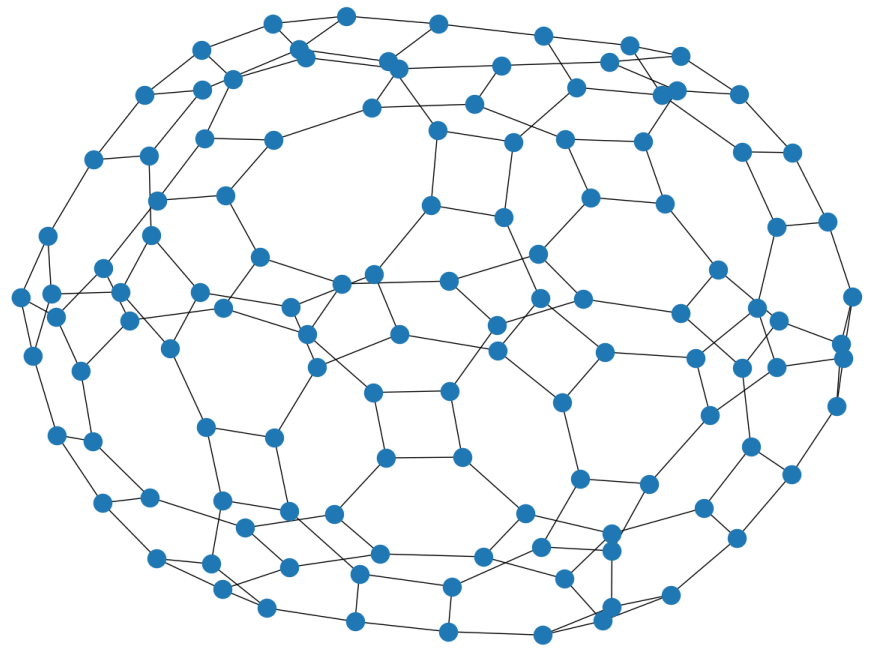

\widetilde A_3

The above diagrams are the only rank-2 affine diagrams. The simplest diagram of rank 3 is \widetilde A_3, which appears similar to 4-Cycle graph.

Similar to how \widetilde A_2’s graph is the tiling of A_2’s, its Cayley graph is the honeycomb of A_3’s. The left image shows the initial branches, while the right image shows the four distinct cells which form the honeycomb. From left to right, the figures contain only edges labelled from abd, abc, bcd, and acd, respectively. The squares always represent commuting pairs on opposite ends of the diagram: ac and bd.

I am not certain in general whether \widetilde A_n generates the honeycomb formed by A_n, but this tessellation should always exist, since the solids formed by the generators of A_n are always permutohedra.

Closing

The diagrams I have studied here are only the smaller ones which I can either visualize or compute. I might have gotten carried away with studying the groups themselves in the 4D case, since there appears to be so much contention. Despite this, I examined only half of the available Platonic solids in 4D, missing out on the 24-cell (Schläfli symbol {3, 4, 3}, F_4), 120-cell (Schläfli symbol {5, 3, 3}, H_4), and 600-cell (Schläfli symbol {3, 3, 5}, H_4). If 4D symmetries are hard to understand, then things can only get worse in higher dimensions.

One of the things I’m curious about is the minimal degree of symmetric group needed to embed the finite diagrams (hereafter \mu). While S_6 is minimal for the octahedral group, it doesn’t appear to be big enough for the icosahedral one. There is a trivial embedding for groups which are direct products given by

\begin{align*} G &\hookrightarrow S_m \sub S_{m+n} \\ H &\hookrightarrow S_n \sub S_{m+n} \\ G \times H &\hookrightarrow S_{m+n} \\ \mu(G \times H) &\le \mu(G) + \mu(H) = m + n \end{align*}

but the groups we’re interested in don’t necessarily have this property.

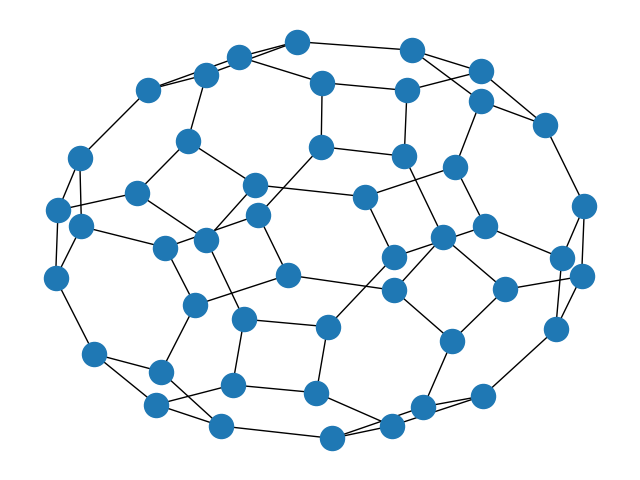

Coset and embedding diagrams made with GeoGebra. Cayley graph images made with NetworkX (GraphViz).

Additional Links

- Point groups in three dimensions (Wikipedia)

- Point groups in four dimensions (Wikipedia)

- Finding the minimal n such that a given finite group G is a subgroup of Sn (Mathematics Stack Exchange)

- Omnitruncated, by Clayton Shonkwiler

Footnotes

For groups without a common name, I’ll instead use W(diagram) (for Weyl) to represent the generated group. For example, in this case, W(B_3) \cong O_h.↩︎

This composition is also called “omnitruncation”.↩︎

The only candidate choices are a and nothing else, every generator but a, or all generators. All other choices violate edge/product constraints from the diagram.↩︎