Code

def spacing(width):

return x**(width + 2) - x**(width + 1) - 1

sympy.Eq(spacing(3), spacing(3).factor())\displaystyle x^{5} - x^{4} - 1 = \left(x^{2} - x + 1\right) \left(x^{3} - x - 1\right)

Interesting results on simple irrational counting systems involving only zero and one.

February 6, 2021

February 8, 2025

This post assumes you have read the first post, which introduces generalized positional counting, and the second, which restricts the focus and specifies the general aim.

Thus far, the systems have been based on quadratic polynomials and two-term linear recurrences, or more directly, carries of width two. Numbers larger than one introduce certain complications to carries. With that in mind, let’s go back to things closer to phinary and Fibonacci.

The Tribonacci numbers (OEIS A000073) come from elongating the Fibonacci recurrence to 3 terms. In other words, this is the carry/recurrence \langle 1,1,1|. The Tribonacci numbers are seeded with two zeros followed by a single one; thus, the sequence begins 0, 0, 1, 1, 2, 4, 7, 13,\dots The Tribonacci constant is the limiting ratio of these numbers (i.e., the positive real root of x^3 - x^2 - x - 1) with approximate value T = 1.8393\dots

The number two bounds both this number and the terms in the recurrence, so its expansion can be deduced:

\textcolor{red}{2} = 1.\textcolor{red}{111}_T = \textcolor{blue}{1.11}1_T = \textcolor{blue}{1}0.001_T

Naturally, the string “111” will be illegal in both systems. The Tribonacci expansions of the integers are as follows:

| n (Decimal) | n (base T) | n (Tribonacci) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 10.001 | 10 |

| 3 | 11.001 | 11 |

| 4 | 100.100011 | 100 |

| 5 | 101.100011 | 101 |

| 6 | 110.101011 | 110 |

| 7 | 1000.101011 | 1000 |

| 8 | 1001.101011 | 1001 |

| 9 | 1010.110100011 | 1010 |

| 10 | 1100.010100011 | 1011 |

Since “111” is a rarer string than “11”, the integral base more closely resembles standard binary.

Extensions of the Fibonacci numbers, which have an n-term recurrence (seeded with n - 1 zeroes followed by a one) are called “n-nacci” or “n-bonacci” numbers. If we discard the seeding terms, then for larger and larger n, this sequence of sequences appears to approach the powers of two.

\begin{matrix} \text{Fibonacci: } & & & 0,& 1,& 1,& 2,& 3,& 5,& 8\dots \\ \text{Tribonacci: } & & 0,& 0,& 1,& 1,& 2,& 4,& 7,& 13\dots \\ \text{Tetranacci: } & 0,& 0,& 0,& 1,& 1,& 2,& 4,& 8,& 15\dots \\ \vdots \\ \text{Binary: } & (\dots,& 0,& 0,& 1,)& 1,& 2,& 4,& 8,& 16\dots \end{matrix}

In the limit, the rightmost and leftmost “1”s in the carry \langle 1, 1, ..., 1, 1 | are infinitely far away from each other. This is similar to binary, in which 2 = 1.1111\dots_2. This argument is clearer if we directly manipulate the carry as a polynomial p_n(x):

\begin{align*} p_n &= x^n - x^{n-1} - … - x - 1 \\ -p_n &= -x^n + x^{n-1} + … + x + 1 \\ x^n - p_n &= x^{n-1} + … + x + 1 \\ x - p_n x^{-n+1} &= 1 + x^{-1} + … x^{-n+2} + x^{-n+1} \\[8pt] \text{Let } n &\rightarrow \infty \\ x &= 1 + x^{-1} + x^{-2} + x^{-3} + … \end{align*}

Since both φ and T are greater than 1, we can assume that x > 1, which causes the x^{-n+1} term to vanish in the limit. Unfortunately, this means p_n should diverge, invalidating the above argument.

Ignoring this, the last line can be manipulated as a power series:

\begin{align*} \frac{1}{1 - x} &= 1 + x + x^2 + x^3 + \dots \\ \frac{1}{1 - (1/x)} &= 1 + x^{-1} + x^{-2} + x^{-3} + \dots \\ x &= \frac{1}{1- (1/x)} \\ x - 1 &= 1 \\ x &= 2 \end{align*}

Which is to imply that, in a non-rigorous sense and by partially assuming the conclusion, that the n-nacci constants approach two.

All carries entirely made up of “1”s correspond to the n-nacci constants. While this would appear to exhaust every sequence without going to negative numbers, it ignores the potential of carries with a “0”.

Starting simple, Narayana’s cows sequence (OEIS A000930) corresponds to the recurrence \langle 1,0,1|. It may be seeded with either three 1’s, or in the same way as above, with a sequence of 0’s followed by a 1. The limiting ratio \psi \approx 1.4656\dots is called the supergolden ratio. The introduction of “0”s turns out to have big implications, since the concatenation trick to devise the expansion of two no longer works. However, hope is not lost.

\begin{gather*} 1\textcolor{red}{1}000_\psi = 10\textcolor{red}{101}_\psi = \textcolor{blue}{101}01_\psi = \textcolor{blue}{1}00001_\psi \\ \textcolor{red}{2} = 1.\textcolor{red}{101}_\psi = \textcolor{blue}{1.1}01_\psi = \textcolor{blue}{1}0.001\textcolor{blue}{1}_\psi = 10.00\textcolor{purple}{11}_\psi = 10.0\textcolor{purple}{1}0000\textcolor{purple}{1}_\psi \end{gather*}

Incredibly, the carry contains not only an explicit rule for “101”, but implicit rules “2” and “11”. This sort of makes sense: since \psi < \varphi, adjacent place values are “too dense”, and therefore we can rewrite the string “11”. On the other hand, attempting to manipulate “1001” and “10001” results in circuiting back to the original string.

\begin{split} 100\textcolor{red}{1}000000_\psi &= 1000\textcolor{red}{101}000_\psi = 1000\textcolor{orange}{1}01000_\psi = 10000\textcolor{orange}{1}1\textcolor{orange}{1}00_\psi \\ &= 10000\textcolor{blue}{11}100_\psi = 1000\textcolor{blue}{1}0010\textcolor{blue}{1}_\psi = 1000100\textcolor{red}{101}_\psi \\ &= 100010\textcolor{red}{1}000_\psi = 1000\textcolor{orange}{101}000_\psi = 100\textcolor{orange}1000000_\psi \\ \\ \textcolor{red}{1}0001000_\psi &= 0\textcolor{red}{101}1000_\psi = 010\textcolor{blue}{11}000_\psi = 01\textcolor{blue}{1}0000\textcolor{blue}{1}_\psi \\ &= 0\textcolor{purple}{11}00001_\psi = \textcolor{purple}{1}0000\textcolor{purple}{1}01_\psi \\ &= 10000\textcolor{red}{101}_\psi = 1000\textcolor{red}{1}000_\psi \end{split}

I call these strings of “0”s sandwiched between “1”s spacings. The smallest spacing, with a width of zero, is the Fibonacci recurrence. If we forbid both the width-1 and width-0 spacings from appearing in supergolden expansions, we obtain the following list:

| n (Decimal) | n (base \psi) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 10.0100001 |

| 3 | 100.0110001 |

| 3 | 100.1000100001 |

| 4 | 110.0001100001 |

| 4 | 1000.1000100001 |

| 5 | 1010.0001100001 |

| 5 | 10000.0010001 |

| 6 | 10001.0010001 |

| 7 | 10010.0110002 |

| 7 | 10010.1000012 |

| 7 | 100000.0001000001 |

| 8 | 100001.0001000001 |

| 9 | 100100.0000001001 |

| 10 | 1000000.0000001001 |

In the above table, some intermediate steps are shown in red, but the last entry for each integer is canonical. Not only does the number of digits grow radically faster than in phinary (or even binary), but there are many more intermediate steps.

For space reasons, I do not show the integral dual. Slowly-growing sequences, which have largely uninteresting integral systems, dominate the rest of this post. Therefore, the remainder of this post will focus solely on fractional systems.

A similar degree 3 recurrence is \langle 0,1,1|. Its root corresponds to the plastic ratio \rho \approx 1.3247\dots. A number of sequences share this recurrence; when seeded with 0, 0, 1 as before, the best match is the Padovan sequence (OEIS A000931), which begins with an additional one.

Since \rho < \psi < \varphi, we should expect that spacings of at least width two are illegal. The system turns out to be even stricter than that: spacings up to and including width three are expandable.

\begin{array}{c|c} \text{Width} & \textcolor{red}{0} & \textcolor{green}{1} & 2 & \textcolor{blue}{3} \\ \hline & 0\textcolor{red}{011}_\rho & 010\textcolor{red}{1}000_\rho & 0\textcolor{red}{1}00\textcolor{red}{1}00000_\rho & 0\textcolor{red}{1}0001_\rho \\ & \textcolor{red}{1}000_\rho & 0100\textcolor{red}{011}_\rho & 00\textcolor{red}{011}\textcolor{red}{011}00_\rho & 00\textcolor{red}{011}1_\rho \\ && 0\textcolor{blue}{10001}1_\rho & 000\textcolor{blue}{11011}00_\rho & 000\textcolor{orange}{111}_\rho \\ && \textcolor{blue}{1}000001_\rho & 00\textcolor{blue}{1}0101000_\rho & 00\textcolor{orange}{1}100_\rho \\ && & 0010\textcolor{green}{101}000_\rho & 0\textcolor{red}{011}00_\rho \\ && & 001\textcolor{green}{1000001}_\rho & \textcolor{red}{1}00000_\rho \\ && & 0\textcolor{red}{011}000001_\rho \\ && & \textcolor{red}{1}000000001_\rho \\\\ \hline & s_0 = \rho^2 & s_1 = \rho s_{5} & s_2 = \rho s_{8} & s_3 = \rho \end{array}

The final line is shorthand for the spacing rules:

With these rules, we can write a canonical expansion expansion for 2:

\begin{align*} \textcolor{red}{2} &= 1.\textcolor{red}{011} = \textcolor{blue}{1.011} = \textcolor{blue}{1}\overbrace{0.0100000}^{8 \text{ digits}}\textcolor{blue}{1} \\ &= \textcolor{purple}{10.01}000001 = \textcolor{purple}{1}00.000000\textcolor{purple}{1}1 \\ &= 100.00000\textcolor{red}{011} = 100.0000\textcolor{red}{1} \end{align*}

Since \rho < \sqrt 2, the largest place value in the expansion of two is \rho^2, which distinguishes it from previous systems.

Similarly to how the width-two and width-three spacings are allowed in the supergolden ratio base, we realize that the width-four spacing cannot be expanded further in the plastic ratio base:

\begin{align*} \textcolor{red}{1}0000\textcolor{red}{1}000 &= 0\textcolor{red}{011}00\textcolor{red}{011} = 001\textcolor{blue}{10001}1 = 00\textcolor{blue}{2}000001 \\ &= \textcolor{blue}{1}000000\textcolor{blue}{1}1 = 100001000 \end{align*}

With these implicit rules derived for spacings of width smaller than three, the plastic expansions of the integers up to ten are as follows:

| n (Decimal) | n (base \rho) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 100.00001 |

| 3 | 101.00001 |

| 3 | 1000.00101 |

| 3 | 1000.01000001 |

| 4 | 10000.0101000000001 |

| 4 | 10000.1000001000001 |

| 5 | 10100.0000001000001 |

| 5 | 100000.1000001000001 |

| 6 | 100001.1000001000001 |

| 6 | 100100.0000001000001 |

| 6 | 1000000.0010001000001 |

| 6 | 1000000.0100000000001 |

| 7 | 1000001.0100000000001 |

| 7 | 1000010.0000100000001 |

| 8 | 1001000.0000100000001 |

| 8 | 10000000.0100100000001 |

| 8 | 10000000.1000000001001 |

| 8 | 10000000.100000001000000001 |

| 9 | 10000100.000000001000000001 |

| 10 | 10001000.001000001000000001 |

Clearly, this base is incredibly sensitive. A number as small as eight has a fractional part as small as \rho^{-18} in its expansion.

When discussing the expandable spacings in the supergolden and plastic bases, they jumped from width one to width three. Did we forgot width 2? The strings “1001” and “10001” are associated to the carries \langle 1, 0, 0, 1| and \langle 1, 0, 0, 0, 1|.

| Spacing Width | Carry | Integral Sequence | Root |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | \langle 1,1| | Fibonacci numbers, Lucas numbers | Golden Ratio, \varphi |

| 1 | \langle 1,0,1| | Narayana’s cows sequence | Supergolden Ratio, \psi |

| 2 | \langle 1,0,0,1| | OEIS A003269 | Unnamed (\upsilon?) |

| 3 | \langle 1,0,0,0,1| \simeq \langle 0,1,1| | Padovan sequence, Perrin sequence | Plastic Ratio, \rho |

I chose the symbol \upsilon since it came from the second half of the Greek alphabet, like the others.

While the width-two spacing is a irreducible polynomial like its predecessors, the width-three one can be factored

\displaystyle x^{5} - x^{4} - 1 = \left(x^{2} - x + 1\right) \left(x^{3} - x - 1\right)

This also means that despite \rho and \psi being cubic roots, \upsilon is irreducibly a quartic root, despite being between them in terms of spacing width.

The right polynomial may be familiar from the previous post as \langle 1, -1 |, which only has complex roots. It happens to be the sixth cyclotomic polynomial (\Phi_6), and allows the width-three spacing to be equivalent to the simpler plastic ratio carry.

As previously stated, the cyclotomic polynomials cause big trouble for carries. Other than factoring, there appears to be no way to derive \langle 0,1,1| from \langle 1,0,0,0,1|. At best, we can observe the following:

\begin{matrix} \langle 1,0,0,0,1| && \langle 0,1,1| \\ \hline 11111 &\iff& 11111 \\ 101110 && 1000111 \\ 1001100 &\iff& 1001100 \\ 10001000 && 1100000 \\ 100000000 &\iff& 100000000 \\ \end{matrix}

The appearance of a cyclotomic factor is not unique to the width-three spacing. Each of the smaller-width rules in the supergolden and plastic bases can be reexamined as polynomials. After converting and factoring, their cyclotomic factors become clear:

\begin{gather*} 11000_\psi = 100001_\psi \\ 1\bar{1}\bar{1}001_\psi = 0 \\ \psi^5 - \psi^4 - \psi^3 + 1 \\ (\psi - 1)(\psi + 1)(\psi^3 - \psi^2 - 1) \\ \Phi_1 \Phi_2 \langle 1,0,1| \\ \\ \begin{gather*} 101000_\rho = 1000001_\rho & 100100000_\rho = 1000000001_\rho \\ 1\bar{1}0\bar{1}001_\rho = 0 & 1\bar{1}00\bar{1}00001_\rho = 0 \\ \rho^6 - \rho^5 - \rho^3 + 1 & \rho^9 - \rho^8 - \rho^5 + 1 \\ (\rho - 1)(\rho^2 + 1)(\rho^3 - \rho - 1) & \dots(\rho^2 - \rho + 1)(\rho^3 - \rho - 1) \\ \Phi_1 \Phi_4 \langle 0,1,1| & \Phi_1 \Phi_2 \Phi_4 \Phi_6 \langle 0,1,1| \end{gather*} \end{gather*}

Though I am uncertain without a proof, it seems that cyclotomic polynomials play a role in spacing out “1”s. This is to say that spacings have a “fundamental” irreducible polynomial. By multiplying certain cyclotomic polynomials by the fundamental, (all?) smaller spacings can produce spacings the size of the fundamental or less.

Naturally, I attempted to write a program to compute lesser spacings from an implicit rule. Generally, this entailed assembling all lesser spacings, then expanding the rightmost 1 if unable to find any spacing, else replacing and continuing. Unfortunately, since it operates in lockstep, it gets stuck easily, and I had little success. My Haskell code can be found here.

The width-three spacing is not fundamental, since it can be factored. We can collect reducible spacings into a table:

| n-spacing | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| Irreducible? | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

In the range given, this table appears to repeat every six terms. We can examine each of these factors directly:

\begin{align*} x^5 - x^4 - 1 &= (x^2 - x + 1) (x^3 - x - 1) \\ &= 1\bar{1}1_x * 10\bar{1}\bar{1}_x \\ x^{11} - x^{10} - 1 &= (x^2 - x + 1) (x^9 - x^7 - x^6 + x^4 + x^3 - x - 1) \\ &= 1\bar{1}1_x * 10\bar{1}\bar{1}0110\bar{1}\bar{1}_x \\ x^{17} - x^{16} - 1 &= (x^2 - x + 1) (x^{15} - x^{13} - \dots + x^4 + x^3 - x - 1) \\ &= 1\bar{1}1_x * 10\bar{1}\bar{1}0110\bar{1}\bar{1}0110\bar{1}\bar{1}_x \\ 5, 11, 17, \dots &= 6n + 5 \end{align*}

Each of these polynomials has \Phi_6 as a common factor. The other factor appears to be a truncation of the repeating string “\underline{0110\bar{1}\bar{1}}”. 1 Interpreted as a power series, this is the reciprocal of -\Phi_6 (OEIS A010892).

As the carry approaches infinite width, the x terms go to 0 for x < 1. This shows that like the n-nacci constants approach two, the spacing constants approach one.

Let’s not get too eager here and instead return to base \upsilon. It should be possible to expand the strings “11” and “101”, since it is the fundamental spacing of width 2. However, we immediately run into an issue:

\begin{array}{c|c} \text{Width} & \textcolor{green}{0} & \textcolor{blue}{1} & \textcolor{red}{2} \\ \hline & 01\textcolor{red}{1}00000_\upsilon & 010\textcolor{red}{1}0000_\upsilon & 0\textcolor{red}{1001}_\upsilon \\ & 010\textcolor{red}{1001}0_\upsilon & 0100\textcolor{red}{1001}_\upsilon & \textcolor{red}{1}0000_\upsilon \\ & 0\textcolor{blue}{101}0010_\upsilon & 0\textcolor{orange}{1001}001_\upsilon \\ & \textcolor{blue}{1}000001\textcolor{blue}{1}_\upsilon & \textcolor{orange}{1}0000001_\upsilon \\ & 100000\textcolor{green}{11}_\upsilon \\ & \vdots \\ \hline & s_0 = \ ? & s_1 = \rho s_6 & s_2 = \rho \end{array}

The width-0 expansion is recursive. If we continue to apply its rule, we generate the string “100001” repeating. Fortunately, each repeating unit is a width-four spacing, which is allowed by the carry.

Repeating expansions imply a representation by geometric series:

\begin{gather*} 1.\underbrace{\underline{0\dots1}}_{n}{}_x = 1 + x^{-n} + x^{-2n} + x^{-3n} + \dots = \frac{1}{1 - (1/x)^n} = \frac{x^n}{x^n - 1} \\ 10 = 1.\underbrace{\underline{0\dots1}}_{n}{}_x ~\iff~ x = \frac{x^n}{x^n - 1} \\ 1 = \frac{x^{n-1}}{x^n - 1} \\ \\ x^{n-1} = x^n - 1 \end{gather*}

The final expression is just the definition of a carry, so we can immediately write:

\begin{align*} 10_\varphi &= 1.\underline{01}_\varphi & & \text{Carry } \langle 1,1| \\ 10_\psi &= 1.\underline{001}_\psi & & \text{Carry } \langle 1,0,1| \\ 10_\upsilon &= 1.\underline{0001}_\upsilon & & \text{Carry } \langle 1,0,0,1| \\ 10_{\rho} &= 1.\underline{00001}_\rho & & \text{Carry } \langle 1,0,0,0,1| = \langle 0,1,1| \end{align*}

This neatly ties repeating spacings in with carries. 2

But we didn’t want “10” as a repeating expansion, we wanted “11”. Attempting to justify with the same strategy:

\begin{align*} 0.11_\upsilon &= 1.\underline{00001}_\upsilon & \text{Carry } \langle 1,0,0,1| \\ \frac{1}{x} + \frac{1}{x^2} &= \frac{x^n}{x^n - 1} \\ x + 1 &= \frac{x^{n+2}}{x^n - 1} \\[8pt] x^{n+1} + x^n - x - 1 &= x^{n+2} \\ x^{n+2} - x^{n+1} - x^n + x + 1 &= 0 \\ x^n(x^2 - x - 1) + x + 1 &= 0 \end{align*}

| n-repeat | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| Irreducible? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

For n = 5, the polynomial factors as the product of \langle 1, 0, 0, 1| and \langle 0, 1, 1|. The second factor should come as no surprise since we know directly that 0.11_\rho = 10_\rho and we already evaluated 10_{\rho} = 1.\underline{00001}_\rho

Checking more n, this polynomial actually seems to be the only reducible one for quite a while.

This bestows some level of intrigue upon the repeating expansion of “11”. Since repeating expansions are required for base \upsilon I will elect to not show the expansion of the integers.

This can be generalized slightly to match any spacing with any repeating spacing:

\begin{gather*} 0.\underbrace{10\dots01}_m = 1.\underbrace{\underline{0\dots01}}_n ~\Leftrightarrow~ \frac{1}{x} + \frac{1}{x^m} = \frac{x^n}{x^n - 1} \\ x^{m-1} + 1 = \frac{x^{n+m}}{x^n - 1} \\ \\ x^{n+m-1} + x^n - x^{m-1} - 1 = x^{n+m}\\ x^{n+m} - x^{n+m-1} - x^n + x^{m-1} + 1 = 0 \\ (x^n)(x^m - x^{m-1} - 1) + x^{m-1} + 1 = 0 \\ \end{gather*}

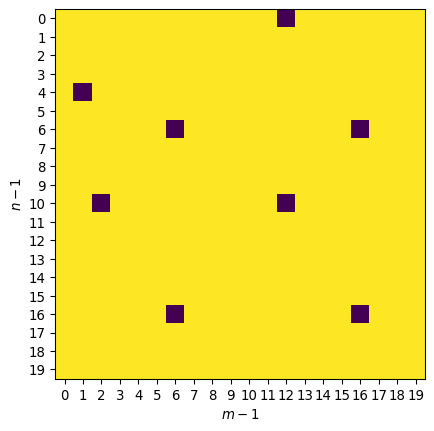

If the polynomial has factors, then fractional systems where those factors are carries have repeating expansions of width n for a spacing of width m. Graphing the tuples of reducible polynomials produces a strange pattern apparently arranged in lines (going from the lower left to the upper right):

The leftmost purple square is the exception, which corresponds to the earlier (m, n) = (2, 5). Every purple square here is a reducible polynomial, the first few of whose factors are:

| (m, n) | Sum | Polynomial Factors |

|---|---|---|

| (2, 5) | 7 | (x^3 - x - 1) (x^4 - x^3 - 1) |

| (3, 11) | 14 | (x^4 - x^3 + x^2 - x + 1) (x^{10} - x^8 - x^7 - x^6 - x^5 + x^3 + x^2 + x + 1) |

| (7, 7) | (x^4 - x^3 + x^2 - x + 1) (x^{10} - x^8 - x^5 + x + 1) |

|

| (13, 1) | (x^4 - x^3 + x^2 - x + 1) (x^{10} + x^7 - x^5 - x^2 + 1) |

|

| (7, 17) | 24 | (x^4 - x^3 + x^2 - x + 1) (x^{20} - x^{18} - x^{15} - x^{12} + x^{10} + x^7 - x^5 + x + 1) |

| (13, 11) | (x^4 - x^3 + x^2 - x + 1) (x^{20} - x^{18} - x^{15} + x^{13} + x^{10} + \dots + x + 1) |

|

| (17, 7) | (x^4 - x^3 + x^2 - x + 1) (x^{20} - x^{18} - x^{15} + x^{13} + x^{12} + \dots + x + 1) |

|

| (17, 17) | (x^4 - x^3 + x^2 - x + 1) (x^{30} - x^{28} - x^{25} + x^{23} + x^{20} - x^{18} - \dots + x + 1) |

Only the first entry has factor that is a carry associated to a spacing. Every other entry appears to have (x^4 - x^3 + x^2 - x + 1) as a common factor, which is the 10th cyclotomic polynomial.

These solutions also have sums which increment in tens, which correspond to the vertical and horizontal lines of purple squares in the image. Both m and n solutions work in a similar way: the symmetric solution (7, 7) has similar solutions (7, 17), (17, 7), and (17, 17). This pattern also holds up in the “next” terms (7, 27), (17, 27), (27, 27), (27, 17), and (27, 7). It appears as though there is a congruence of m + n\ (\text{mod } mn), where m and n come from the exception (2, 5). This pattern is similar to the one in which one in every six spacings can be factored.

In summary, the Fibonacci recurrence can be generalized in at least two two different ways. Introducing “0”s into the carry is more touch-and-go than would otherwise seem, though they produce (with much effort) valid bases.

The next post will explore a more distant cousin of the Fibonacci numbers, and other strange power series which arise from its discussion.

Since I already use the overbar for negative digits, I gather repeating terms using an underline as a vinculum.↩︎

Recall that when we naively computed ten in base φ, we got “10100.0100101010101010101”. After a certain point, this expansion alternates between 0 and 1. Assuming that this is true repetition and applying 10_\varphi = 1.\underline{01}_\varphi, one obtains “10100.0101”, which is canonical. ↩︎