Counting in 2D, Part 2: Reorienting Polynomials

Geometric properties of certain 2D systems and attempts to classify them.

Previously, I explored some very basic 2D counting systems, which turned out to include sandpiles. As the name suggests, these planar numbers require a discrete grid of numbers to contain them. What follows is a deeper investigation into this natural extension of positional systems.

Direction of Propagation

Given a carry (expressed as a polynomial in two variables or a grid) and an increasing sequence of integers, the expansions of the sequence will appear to propagate in a certain direction. Recall that from the last post, we know that x + y = 2 and a certain case of the folium of Descartes will make similar patterns:

\begin{gather*} & ~ & \text{Folium} \\ x + y - 2 & ~ & x^3 + y^3 - 2xy \\ \begin{array}{|c} \hline \bar{2} & 1 \vphantom{2^{2^2}} \\ 1 \end{array} & ~ & \begin{array}{|c} \hline 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & \bar{2} \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \end{gather*}

The general direction in which we carry can be understood as the directions from the negative term of the carry (hereafter pseudo-base) to the other terms. These can interpreted vectors extending from the pseudo-base to every other term. The simplest way to get these vectors is by placing the pseudo-base at the constant position and reading off the exponent of the other terms.

\begin{gather*} \begin{array}{|c} \hline \bar{2} & \textcolor{red}{1} \vphantom{2^{2^2}} \\ \textcolor{blue}{1} \end{array} & ~ & \begin{array}{c|cc} 0 & 0 & 0 & \textcolor{red}{1} \\ \hline 0 & \bar{2} \vphantom{2^{2^2}} \\ 0 \\ \textcolor{blue}{1} \end{array} \\ \begin{matrix} \textcolor{red}{ x^1 y^0 } \implies \langle 1, 0 \rangle \\ \textcolor{blue}{ x^0 y^1 } \implies \langle 0, 1 \rangle \end{matrix} & ~ & \begin{matrix} \textcolor{red}{ x^2 y^{-1} } \implies \langle 2, -1 \rangle \\ \textcolor{blue}{ x^{-1} y^2 } \implies \langle -1, 2 \rangle \end{matrix} \end{gather*}

It is clear that as we count, the expansions can extend only in a linear combination of these vectors. However, they cannot propagate in the reverse direction, as there is no sense of “backwards”.

Balancing Act

We can naively balance the carry by adding additional carry digits. To do this, we just need to double the pseudo-base and add reflections each vector in it. Equivalently, this adds the carry with the carry where we have replaced x and y with their reciprocals.

If we balance the left carry, it yields the Laplacian. But what about the right? Unsurprisingly, it just stretches the expansions along the different “basis” vectors.

\textcolor{red}{ x^{-2} y^{1} } + x^{-1} y^{2} + \textcolor{blue}{ x^{1} y^{-2} } + x^{2} y^{-1} - 4 \\ \begin{array}{cc|ccc} & & & \textcolor{blue}{1} \\ & & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \hline & 0 & \bar{4} & 0 \vphantom{2^{2^2}} \\ \textcolor{red}{1} & 0 & 0 \\ & 1 \end{array} \\ \text{Added Vectors:} \\ \begin{matrix} \textcolor{red}{ \langle -2, 1 \rangle } \\ \textcolor{blue}{ \langle 1, -2 \rangle } \end{matrix}

Half-Balanced

The Laplacian carry is remarkably balanced, but it provokes the question of what the expansions look like if there are only three directions to propagate. The intuition from above says that it should span a half-plane, up from the quarter-plane that x + y = 2 spans.

\textcolor{red}{ x^{-1} } + x^1 + y^1 - 3 \\ \begin{array}{c|cc} \hline \textcolor{red}{1} & \bar{3} & 1 \vphantom{2^{2^2}} \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \end{array} \\ \text{Added Vector:} \\ \begin{matrix} \textcolor{red}{ \langle -1, 0 \rangle } \end{matrix}

Fortunately, this is the case.

2D Carry Types

Based on the extent of the vectors, in general there appear to be four classes:

- The degenerate one-dimensional case

- The carry is equivalent to the product of a polynomial in a single variable and any power x and/or y.

- Quarter-planes, like x + y = 2

- Arise when the inverses of the vectors are inaccessible.

- Half-planes, like the above “semi-”Laplacian

- Arise when two vectors are collinear and point in opposite directions, but every other vector is either on one side of this line or are also collinear.

- Full planes, like the Laplacian

- Arise when the inverses of both vectors are accessible.

Quarter-plane is a bit of a misnomer. Technically, the fraction of the plane spanned is between 0 and 1/2 noninclusive (as these bounds correspond to the previous and next cases respectively). For example, x + y = 2 actually to a quarter-plane, as the first row/column (which contain binary expansions) are unbounded. However, the Folium encompasses slightly more of the plane, or…

\frac{1}{2\pi}\arccos \left ( \frac{\langle 2, -1 \rangle \cdot \langle -1, 2 \rangle} {\| \langle 2, -1 \rangle \| \| \langle -1, 2 \rangle \|} \right) = \frac{1}{2\pi} \arccos \left ( -\frac 4 5 \right ) \approx 0.397584

…about 39% of the plane. This is still smaller than the half-plane case.

Hunting for Implicitness

With these categories in mind, I would now like to shift focus. All systems discussed thus far have been explicit and irreducible, meaning they are not derived from any “simpler” implicit rules. Do such rules exist, and cam we find any?

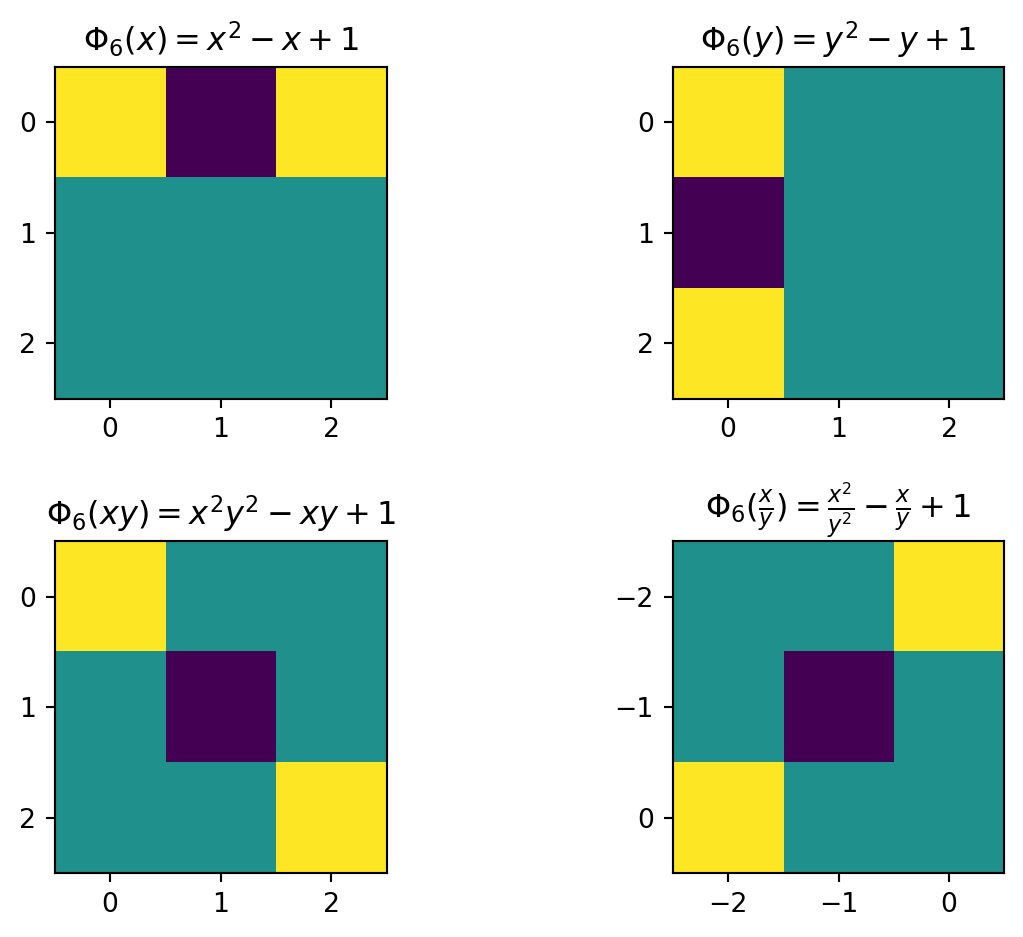

As mentioned previously, in the 1D case, we form explicit carries from implicit ones by multiplying the latter by cyclotomic polynomials. It would be convenient if the same were true in two dimensions – we generate an explicit 2D carry from the product of some input polynomial and a cyclotomic polynomial in x and y. However, I would like to leverage the visual representation used previously, since working with coefficients is linear, unintuitive, and most importantly, annoying.

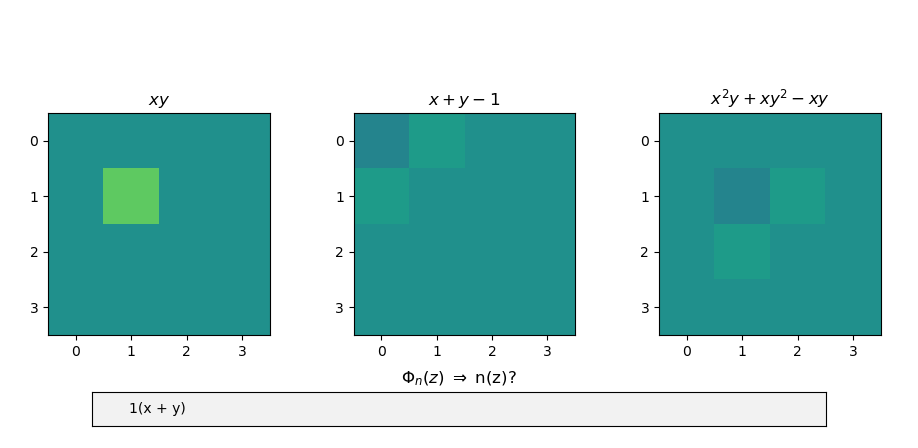

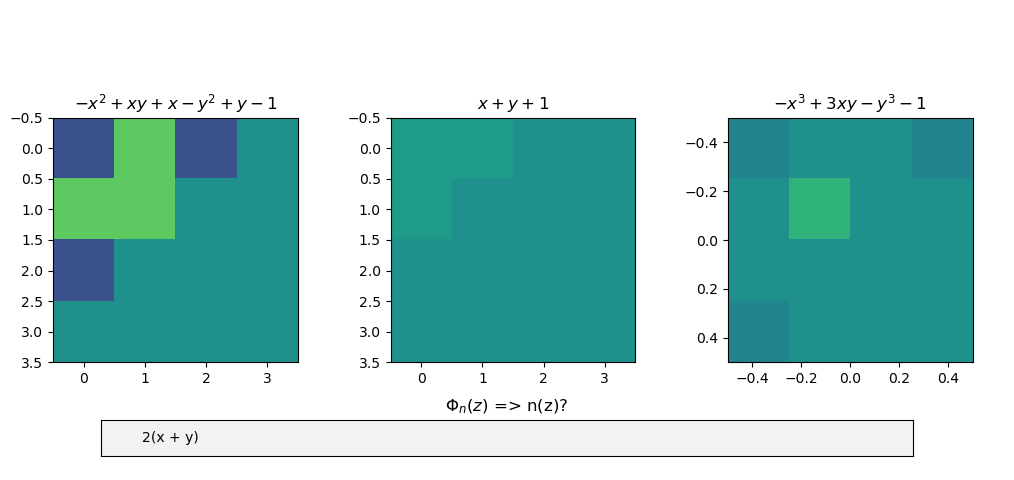

Above is a screenshot of (my admittedly low-effort) attempt to ameliorate these shortcomings. The left image is clickable, with the coefficients incrementing with left clicks and decrementing with right. The text box controls the second multiplicand in the center image by selecting a cyclotomic polynomial and evaluating it with a particular expression. The right image is the product.

It could obviously be improved by showing the coefficients in the picture and using color to only indicate sign. However, there is a benefit to hiding coefficients behind solid colors. For instance, I don’t need to recognize numerals to pinpoint what the product should look like.

Degenerate Expressions

I have chosen to evaluate the right term (center image) at x + y for a reason. Choosing x or y on their own is a poor decision because they change nothing from the one dimensional case. Put another way, when arranged in a grid, the coefficients are all collinear. At first blush, xy seems like a decent pick, but it has the exact same problem; the line simply extends along the diagonal instead. x/y has the same problem, but it is instead collinear along the anti-diagonals. We allow negative exponents for the same reason we can carry at any location in an expansion

It should go without saying that these are all degenerate, and can only span a line. On the other hand, expressions like the sum of x and y form triangles, 2D shapes from which it is possible to build our goal polynomial. Since x + y is symmetric in x and y, it is expected that the products have a similar sense of symmetry.

First Results

The first explicit product I was able to find is above. It can be decomposed as the folium of Descartes, but with an extra term to the upper-left of the pseudo-base. The implicit carry (the left multiplicand) describes the rearrangement of coefficients in a backwards L-shape to and from a sparser upside-down L-shape. Since the coefficients of this factor sum to zero, it passes through (1, 1).

\begin{gather*} \text{Folium} & ~ & \text{New carry} \\ x^3 + y^3 - 2xy & ~ & x^3 + y^3 + 1 - 3xy \\ \begin{array}{|c} \hline 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & \bar{2} \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} & ~ & \begin{array}{|c} \hline 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & \bar{3} \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \end{gather*}

Cousin Systems

My first thought upon seeing this carry was to see what makes counting in this system different from its “neighbors”. By this, I mean moving the x^3 and y^3 terms further inward and outward.

\begin{gather*} x + y + 1 - 3xy & x^2 + y^2 + 1 - 3xy \\ \begin{array}{|c} \hline 1 & 1 \\ 1 & \bar{3} \\ \end{array} & \begin{array}{|c} \hline 1 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & \bar{3} \\ 1 \end{array} \\ \textcolor{red} {x^3 + y^3 + 1 - 3xy} & x^4 + y^4 + 1 - 3xy \\ \textcolor{red} { \begin{array}{|c} \hline 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & \bar{3} \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} } & \begin{array}{|c} \hline 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & \bar{3} \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \end{gather*}

All polynomials besides the one under consideration (highlighted in red) are irreducible. This means that these carries hide no implicit rules, and are as fundamental as the Laplacian or x + y = 2.

Analyzing the carry vectors, it is clear that the pattern produced by each should be different:

\begin{gather*} x^{-1} y^{0} + x^{-1} y^{-1} + x^{0} y^{-1} - 3 & x^{-1} y^{1} + x^{-1} y^{-1} + x^{1} y^{-1} - 3 \\ \begin{matrix} \langle -1, 0 \rangle \\ \langle -1, -1 \rangle \\ \langle 0, -1 \rangle \end{matrix} & \begin{matrix} \langle -1, 1 \rangle \\ \langle -1, -1 \rangle \\ \langle 1, -1 \rangle \end{matrix} \\ x^{-1} y^{2} + x^{-1} y^{-1} + x^{2} y^{-1} - 3 & x^{-1} y^{3} + x^{-1} y^{-1} + x^{3} y^{-1} - 3 \\ \begin{matrix} \langle -1, 2 \rangle \\ \langle -1, -1 \rangle \\ \langle 2, -1 \rangle \end{matrix} & \begin{matrix} \langle -1, 3 \rangle \\ \langle -1, -1 \rangle \\ \langle 3, -1 \rangle \end{matrix} \\ \end{gather*}

The vectors in the top-left carry contain only negative numbers, so it will tend toward the quarter-plane case like x + y = 2. In the top-right carry, all vectors are equidistant and meet at right (and straight) angles. This means that it is a 45° rotation of the altered Laplacian, which spans a half-plane. The remaining two should both propagate into the full plane. Is this reflected in the counting videos?

Counting in each of the x^n + y^n + \ldots systems

Indeed it is. However, while the discovered carry remarkably remains centered, the final one tends more toward propagating to the lower right. It has somehow exceeded a threshold that the centered one has not.

Incidentally, the L-shapes in the implicit carry (which I noted can be interchanged) never turn up, and the “initial rule” is useless. Phinary, the simplest implicit case in one dimension, still requires the initial rule to go from the expansion of two (10.01) to three (100.01).

Isosceles Rotations

One of the similar carries is a rotation of a pattern we were already familiar with, like the folium was to x + y = 2 Does this mean we can rotate the centered pattern? If so, is will the carry polynomial still be factorable?

Naively, the following carry might look similar…

\begin{array}{|c} \hline & & \textcolor{red}{1} \\ & & \bar{3} \\ \textcolor{green}{1} & & & & \textcolor{blue}{1} \end{array} \\ \begin{matrix} \textcolor{red}{\langle 0,-1 \rangle} \\ \textcolor{green}{\langle -2,1 \rangle} \\ \textcolor{blue}{\langle 2,1 \rangle} \\ \text{Angle to top} \approx 116° \end{matrix}

But there are only even numbers in the first component of each vector. Therefore, the carry below will produce the same pattern.

\begin{array}{|c} \hline & \textcolor{red}{1} \\ & \bar{3} \\ \textcolor{green}{1} && \textcolor{blue}{1} \end{array} \\ \begin{matrix} \textcolor{red}{\langle 0,-1 \rangle} \\ \textcolor{green}{\langle -1,1 \rangle} \\ \textcolor{blue}{\langle 1,1 \rangle} \\ \text{Angle to top} = 135° \end{matrix}

Neither of these are similar to the original. For comparison, the largest angle in the nonrotated case is ~108°. In fact, the shape is much closer to the similar orientation with x^4 + y^4 + \ldots terms.

Checking Magnitudes

Measuring these quantities as angles is a bit of a lie. Since all of these triangles are isosceles, two of the vectors have equal magnitude. Further, each can be characterized by the ratio between them and the final vector’s magnitude. The previous two triangles have ratio:

\\ \frac{m_1}{n_1} = \frac{\| \langle -2, -1 \rangle \|}{\| \langle 0, -1 \rangle \|} = \frac{\sqrt 5}{1} = \sqrt 5 \\ \frac{m_2}{n_2} = \frac{\| \langle -1, -1 \rangle \|}{\| \langle 0, -1 \rangle \|} = \frac{\sqrt 2}{1} = \sqrt 2

The triangle we are trying to rotate has ratio:

\frac{m}{n} = \frac{\| \langle 2, -1 \rangle \|}{\| \langle -1, -1 \rangle \|} = \frac{\sqrt 5}{\sqrt 2} = \frac{\sqrt {10}}{2}

Obviously, one cannot express \sqrt 10 from only one of \sqrt 2 or \sqrt 5. Fortunately, this suggests the rotation:

\begin{gather*} \begin{array}{|c} \hline & & & \textcolor{red}{\bar{1}} \\ \\ & & & \bar{3} \\ \textcolor{green}{1} & & & & & & \textcolor{blue}{1} \end{array} ~~ \begin{matrix} \textcolor{red}{\langle 0,-2 \rangle} \\ \textcolor{green}{\langle -3,1 \rangle} \\ \textcolor{blue}{\langle 3,1 \rangle} \\ \end{matrix} \\ \frac{\| \langle -3, 1 \rangle \|}{\| \langle 0, -2 \rangle \|} = \frac{\sqrt {10}}{2} \\ \end{gather*}

The counting video looks very promising, but can the polynomial factored? Fortunately, yes.

\begin{gather*} x^{6} y^{3} + x^{3} + y^{3} - 3 x^{3} y^{2} &=& (x^{4} y^{2} - x^{3} y - x^{2} y^{2} + x^{2} - x y + y^{2}) \\ && (x^2 y + x + y ) \\ \begin{array}{|c} \hline & & & 1 \\ \\ & & & \bar{3} \\ 1 & & & & & & \bar{1} \end{array} &=& \begin{array}{|c} \hline & & 1 & \\ & \bar{1} & & \bar{1} & \\ 1 & & \bar{1} & & 1 \\ \end{array} ~~\cdot~~ \begin{array}{|c} \hline & 1 & \\ 1 & & 1 \end{array} \\ & & (x y^{2} + x + y ) = \Phi_2 \left ( \frac{y}{x} + xy \right ) x \end{gather*}

As noted, the the rightmost polynomial can still be expressed from \Phi_2.

All powers of x in the product are multiples of 3. We can divide these out to produce a similar carry, as we did before. Doing so preserves the shape of counting, but destroys the factorization, as the result is irreducible.

\begin{array}{|c} \hline & \textcolor{red}{1} & \\ \\ & \bar{3} & \\ \textcolor{green}{1} & & \textcolor{blue}{1} \end{array} ~~ \begin{matrix} \textcolor{red}{\langle 0,2 \rangle} \\ \textcolor{green}{\langle -1,-1 \rangle} \\ \textcolor{blue}{\langle 1,-1 \rangle} \\ \end{matrix} \\ \frac{| \langle -1, -1 \rangle |}{| \langle 0,2 \rangle |} = \frac{\sqrt 2}{2}

All of these similar systems is share something in common: the pseudo-base is located at the centroid of the triangle formed by the remaining digits. This is most obvious from the fact that the sum of all three vectors equals \vec 0 in all three cases. The “threshold we exceeded” when comparing the unrotated system’s neighbors was the centroid transitioning between being closer to the upper point or the lower two points.

The position of the centroid is unchanged so long as the lower two points have the same midpoint as above. Therefore, all triangular barycentric carries should share this similar pattern.

Closing

Carries intrinsically possess a few invariants. For one, they must apply at any location in an expansion, a form of translational symmetry. No matter if we multiply or divide by x or y, the polynomial retains its general appearance, as well as whether or not it is irreducible. The above method shows that rotational symmetry also exists for polynomials beyond interchanging x and y.

For integers, carries possess a symmetry which polynomials do not: the ability to contract and expand bases, meaning that in some sense, P(x) \sim P(x^k) for any k. This preserves the counting system despite expansions and contractions which pay no regard for reducibility. This is also the reason that systems like base-\sqrt 2 are so uninteresting: for integers, it just amounts to spaced-out binary.

Three questions that immediately come to mind are:

- Not all integers can be written as the sum of two squares. Are there any (reducible) polynomials which have no nontrivial rotation?

- The Brahmagupta-Fibonacci identity implies that such numbers are closed under multiplication. This means that it is always possible to reorient the triangle in the method shown above.

- After compacting the counting system, can reducibility be recovered for other scaling factors than the one started with? What about from an irrational scaling (as by a rotation)?

- I am not equipped to answer this.

- Some geometry is impossible in the 2D square lattice – for example, it contains no equilateral triangles. Equilateral triangles do however exist in the 3D square lattice. Are there 2D systems which must be embedded in 3D dimensions, or can they always be rotated and reduced?

- Again, I am not equipped to answer this.

Regardless, it is pleasing that the exponents in polynomials can easily be interpreted as the components of vectors. The primary geometrical approach to such objects is to plot the curve or surface containing points which (at least approximately) satisfies the equation. Here however, basic coordinate geometry exists without needing to define evaluation. Moreover, geometry, linear algebra, and polynomial number theory all at once have a role to play in the story of these bizarre fractal patterns.